Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract Disorders

Pneumothorax

PNEUMOTHORAX

Pneumothorax

occurs when the parietal or visceral pleura is breached and the pleural space

is exposed to positive atmospheric pressure. Normally the pressure in the pleural

space is negative or subatmospheric compared to atmospheric pressure; this

negative pressure is required to maintain lung inflation. When either pleura is

breached, air enters the pleural space, and the lung or a portion of it

collapses. Types of pneumothorax include simple, traumatic, and tension

pneumothorax.

Simple Pneumothorax

A

simple, or spontaneous, pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space

through a breach of either the parietal or visceral pleura. Most commonly this

occurs as air enters the pleural space through the rupture of a bleb or a

bronchopleural fistula. A spon-taneous pneumothorax may occur in an apparently

healthy per-son in the absence of trauma due to rupture of an air-filled bleb,

or blister, on the surface of the lung, allowing air from the airways to enter

the pleural cavity. It may be associated with diffuse in-terstitial lung

disease and severe emphysema.

Traumatic Pneumothorax

Traumatic

pneumothorax occurs when air escapes from a lacera-tion in the lung itself and

enters the pleural space or enters the pleural space through a wound in the

chest wall. It can occur with blunt trauma (eg, rib fractures) or penetrating

chest trauma. It may also occur from abdominal trauma (eg, stab wounds or

gun-shot wounds to the abdomen) and from diaphragmatic tears. Traumatic

pneumothorax may occur with invasive thoracic pro-cedures (ie, thoracentesis,

transbronchial lung biopsy, insertion of a subclavian line) in which the pleura

is inadvertently punc-tured, or with barotrauma from mechanical ventilation.

Traumatic

pneumothorax resulting from major injury to the chest is often accompanied by

hemothorax (collection of blood in the pleural space resulting from torn

intercostal vessels, lacer-ations of the great vessels, and lacerations of the

lungs). Often both blood and air are found in the chest cavity

(hemopneu-mothorax) after major trauma. Chest surgery can cause what is

classified as a traumatic pneumothorax as a result of the entry into the

pleural space and the accumulation of air and fluid in the pleural space.

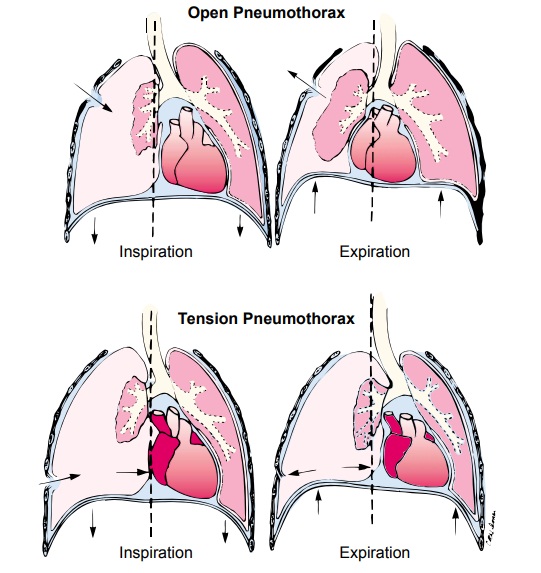

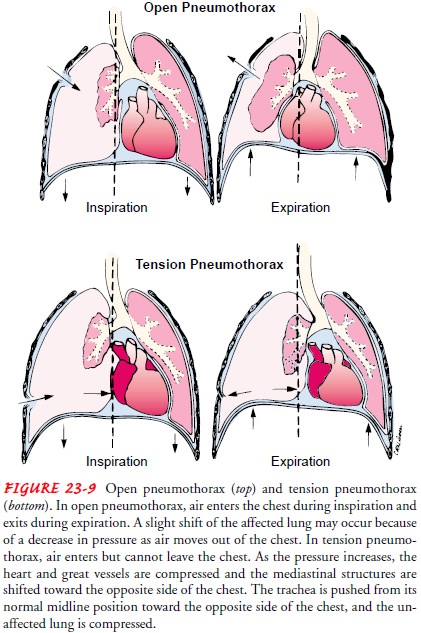

Open

pneumothorax is one form of traumatic pneumothorax. It occurs when a wound in

the chest wall is large enough to allow air to pass freely in and out of the

thoracic cavity with each at-tempted respiration. Because the rush of air

through the hole in the chest wall produces a sucking sound, such injuries are

termed sucking chest wounds. In such patients, not only does the lung collapse,

but the structures of the mediastinum (heart and great vessels) also shift

toward the uninjured side with each inspiration and in the opposite direction

with expiration. This is termed me-diastinal flutter or swing, and it produces

serious circulatory problems.

Clinical Manifestations

The

signs and symptoms associated with pneumothorax depend on its size and cause.

Pain is usually sudden and may be pleuritic. The patient may have only minimal

respiratory distress with slight chest discomfort and tachypnea with a small

simple or un-complicated pneumothorax. If the pneumothorax is large and the

lung collapses totally, acute respiratory distress occurs. The pa-tient is

anxious, has dyspnea and air hunger, has increased use of the accessory

muscles, and may develop central cyanosis from se-vere hypoxemia. Severe chest

pain may occur, accompanied by tachypnea, decreased movement of the affected

side of the tho-rax, a tympanic sound on percussion of the chest wall, and

de-creased or absent breath sounds and tactile fremitus on the affected side.

Medical Management

Medical

management of pneumothorax depends on its cause and severity. The goal of

treatment is to evacuate the air or blood from the pleural space. A small chest

tube (28 French) is inserted near the second intercostal space; this space is

used because it is the thinnest part of the chest wall, minimizes the danger of

contact-ing the thoracic nerve, and leaves a less visible scar. If the patient

also has a hemothorax, a large-diameter chest tube (32 French or greater) is

inserted, usually in the fourth or fifth intercostal space at the midaxillary

line. The tube is directed posteriorly to drain the fluid and air. Once the

chest tube or tubes are inserted and suction is applied (usually to 20 mm Hg

suction), effective de-compression of the pleural cavity (drainage of blood or

air) occurs.

If

an excessive amount of blood enters the chest tube in a rel-atively short

period, an autotransfusion may be needed. This technique involves taking the

patient’s own blood that has been drained from the chest, filtering it, and

then transfusing it back into the patient’s vascular system.

In

such an emergency, anything may be used that is large enough to fill the chest

wound—a towel, a handkerchief, or the heel of the hand. If conscious, the

patient is instructed to in-hale and strain against a closed glottis. This

action assists in re-expanding the lung and ejecting the air from the thorax.

In the hospital, the opening is plugged by sealing it with gauze impreg-nated

with petrolatum. A pressure dressing is applied. Usually, a chest tube

connected to water-seal drainage is inserted to permit air and fluid to drain.

Antibiotics usually are prescribed to com-bat infection from contamination.

The

severity of open pneumothorax depends on the amount and rate of thoracic

bleeding and the amount of air in the pleural space. The pleural cavity can be

decompressed by needle aspira-tion (thoracentesis) or chest tube drainage of

the blood or air. The lung is then able to re-expand and resume the function of

gas ex-change. As a rule of thumb, the chest wall is opened surgically

(thoracotomy) when more than 1,500 mL of blood is aspirated initially by

thoracentesis (or is the initial chest tube output) or when chest tube output

continues at greater than 200 mL/hour. The urgency with which the blood must be

removed is deter-mined by the respiratory compromise. An emergency thoracot-omy

may also be performed in the emergency department if there is suggested

cardiovascular injury secondary to chest or penetrat-ing trauma.

Tension Pneumothorax

A

tension pneumothorax occurs when air

is drawn into the pleural space from a lacerated lung or through a small hole

in the chest wall. It may be a complication of other types of pneumo-thorax. In

contrast to open pneumothorax, the air that enters the chest cavity with each

inspiration is trapped; it cannot be expelled during expiration through the air

passages or the hole in the chest wall. In effect, a one-way valve or ball

valve mechanism occurs where air enters the pleural space but cannot escape.

With each breath, tension (positive pressure) is increased within the affected

pleural space. This causes the lung to collapse and the heart, the great

vessels, and the trachea to shift toward the unaffected side of the chest

(mediastinal shift). Both respiration and circulatory function are compromised

because of the increased intrathoracic pressure. The increased intrathoracic

pressure decreases venous return to the heart, causing decreased cardiac output

and impair-ment of peripheral circulation. In extreme cases, the pulse may be

undetectable—this is known as pulseless electrical activity.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The

clinical picture is one of air hunger, agitation, increasing hy-poxemia,

central cyanosis, hypotension, tachycardia, and profuse diaphoresis. A

comparison of open and tension pneumothorax is shown in Figure 23-9.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

If

a tension pneumothorax is suspected, the patient should im-mediately be given a

high concentration of supplemental oxygen to treat the hypoxemia, and pulse

oximetry should be used to monitor oxygen saturation.

In an emergency situation, a tension pneumothorax can be de-compressed or quickly converted to a simple pneumothorax by inserting a large-bore needle (14-gauge) at the second intercostal space,

midclavicular line on the affected side. This relieves the pressure and vents

the positive pressure to the external environ-ment. A chest tube is then

inserted and connected to suction to remove the remaining air and fluid,

re-establish the negative pressure, and re-expand the lung. If the lung

re-expands and air leakage from the lung parenchyma stops, further drainage may

be unnecessary. If a prolonged air leak continues despite chest tube drainage

to underwater seal, surgery may be necessary to close the leak.

Related Topics