Chapter: Psychology: Learning

Instrumental Conditioning: Changing Behaviors or Acquiring Knowledge?

Changing

Behaviors or Acquiring Knowledge?

We’ve almost finished our

discussion of instrumental conditioning, except for one cru-cial question: What

is it exactly that animals learn in an instrumental conditioning procedure? The

law of effect implies that the learning is best understood as a change in

behavior, in which responses are either being strengthened or weakened by the

mechanical effects of reinforcement. From the earliest days of learning theory,

however, there was an alternative view of conditioning—one asserting that

behavior change isn’t the key; what matters instead is the acquisition of new

knowledge.

One of the most prominent

proponents of this alternative view was Edward C. Tolman (1886–1959; Figure

7.26), and many forms of evidence support his position. For example, consider

cases of latent learning—learning

that takes place without any corresponding change in behavior. In one

experiment, rats were allowed to explore a maze, without any reward, for 10

days. During these days, there was no detectable change in the rats’ behavior;

and so, if we define learning in terms of behavior change, there was no

learning. But in truth the rats were

learning—and in particular, they were gaining knowledge about how to navigate

the maze’s corridors. This became obvious on the 11th day, when food was placed

in the maze’s goal box for the first time. The rats learned to run to this goal

box, virtually without error, almost immediately. The knowledge they had

acquired earlier now took on motivational significance, so the animals swiftly

displayed what they had learned (Tolman & Honzik, 1930; also H. Gleitman,

1963; Tolman, 1948).

In this case, the knowledge the

rats had gained can be understood as a mental

map of the maze—an internal representation of spatial layout that indicates

what is where and what leads to what. Other evidence suggests that many species

rely on such maps—to guide their foraging for food, their navigation to places

of safety, and their choice of a path to the watering hole. These maps can be

relatively complex and are typically quite accurate (Gallistel, 1994; J. Gould,

1990).

CONTINGENCY IN INSTRUMENTAL CONDITIONING

To understand latent learning or cognitive maps, we need to emphasize what an organ-ism knows more than what an organism does. We also need to consider an organism’s cognition for another reason: Recall that, in our discussion of classical conditioning, we saw that learning doesn’t depend only on the CS being paired with the US; instead, the CS needs to predict the US, telling the animal when the US is more likely and when it’s less likely. Similarly, instrumental conditioning doesn’t depend only on responses being paired with rewards. Instead, the response needs to predict the reward, so that (for example) the probability of getting a pellet after a lever press has to be greater than the probability of getting it without the press.

What matters for instrumental

conditioning, therefore, is not merely the fact that a reward arrives after the

response is made. Instead, what matters is the relationship between responding and getting the reward, and this

relationship actually gives the animal some control over the reward: By

choosing when (or whether) to respond, the animal itself can determine when the

reward is delivered. And it turns out that this con-trol is important, because

animals can tell when they’re in control and when they’re not—and they clearly

prefer being in control.

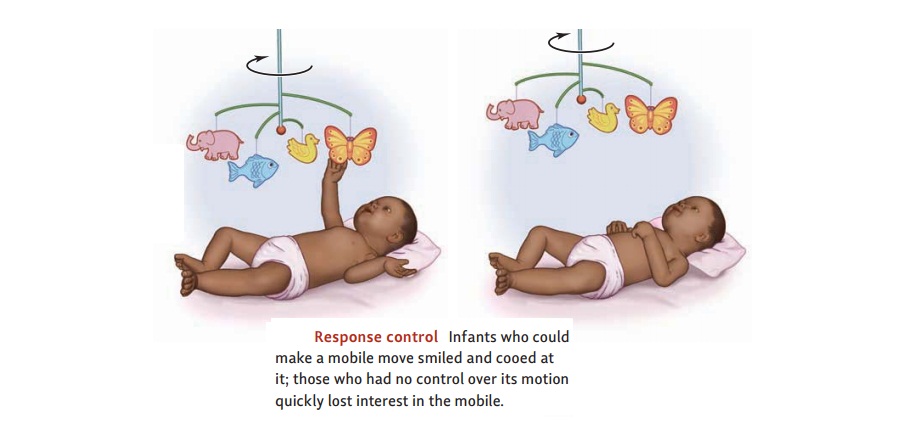

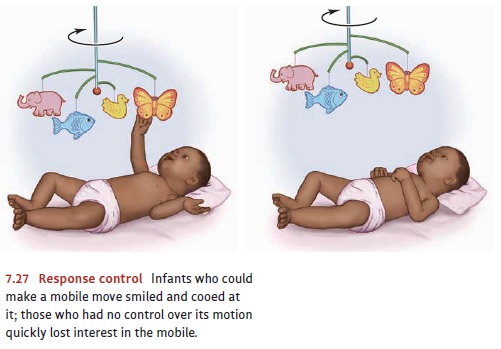

One line of evidence comes from a

study in which infants were placed in cribs that had colorful mobiles hanging

above them. Whenever the infants moved their heads, they closed a switch in

their pillows; this activated the overhead mobile, which spun merrily for a

second or so. The infants soon learned to shake their heads about, making their

mobiles turn. They evidently enjoyed this, smiling and cooing at their mobiles,

clearly delighted to see the mobiles move.

A second group of infants was

exposed to a similar situation, but with one important difference: Their mobile

turned just as often as the mobile for the first group; but it was moved for

them, not by them. This difference turned out to be crucial. After a few days,

these infants no longer smiled and cooed at the mobile, nor did they seem

particularly interested when it turned. This suggests that what the first group

of infants liked about the mobile was not that it moved, but that they made it

move. Even a 2-month-old infant wants to be the master of his own fate (J. S.

Watson, 1967; Figure 7.27).

This study with infants

illustrates the joy of mastery. Another series of studies demonstrates the

despair of no mastery at all. These studies focus on learnedhelplessness—an acquired sense that one has lost control

over one’s environment,with the sad consequence that one gives up trying

(Seligman, 1975).

The classic experiment on learned helplessness used two groups of dogs, A and B, which received strong electric shocks while strapped in a hammock. The dogs in group A were able to exert some control over their situation: They could turn the shock off whenever it began simply by pushing a panel that was placed close to their noses. The dogs in group B had no such power. For them, the shocks were inescapable. But the number and duration of the shocks were the same as for the first group. This was guar-anteed by the fact that, for each dog in group A, there was a corresponding animal in group B whose fate was yoked to that of the first dog. Whenever the group A dog was shocked, so was the group B dog. Whenever the group A dog turned off the shock, the shock was turned off for the group B dog. Thus, both groups experienced exactly the same level of physical suffering; the only difference was what the animals were able to do about it. The dogs in group A had some control; those in group B could only endure.

What did the group B dogs learn

in this situation? To find out, both groups of dogs were next presented with a

task in which they had to learn to jump from one compart-ment to another to

avoid a shock. The dogs in group A learned easily. During the first few trials,

they ran about frantically when the shock began but eventually scrambled over

the hurdle into the other compartment, where there was no shock. Based on this

experience, they soon learned to leap over the hurdle the moment the shock

began, eas-ily escaping the aversive experience. Then, with just a few more

trials, these dogs learned something even better: They jumped over the hurdle

as soon as they heard the tone signaling that shock was about to begin; as a

result, they avoided the shock entirely.

Things were different for the

dogs in group B, those that had previously experienced the inescapable shock.

Initially, these dogs responded to the electric shock just like the group A

dogs did—running about, whimpering, and so on. But they soon became much more

passive. They lay down, whined, and simply took whatever shocks were delivered.

They neither avoided nor escaped; they just gave up. In the earlier phase of

the experiment, they really had been objectively helpless; there truly was

nothing they could do. In the shuttle box, however, their helplessness was only

subjective because now they did have a way to escape the shocks. But they never

discovered it, because they had learned to be helpless (Seligman & Maier,

1967).

Martin Seligman, one of the

discoverers of the learned helplessness effect, asserts that depression in

humans can develop in a similar way. Like the dog that has learned to be

helpless, Seligman argues, the depressed patient has come to believe that

nothing she does will improve her circumstances. And Seligman maintains that,

like the dog, the depressed patient has reached this morbid state by

experiencing a situation in which she really was helpless. While the dog

received inescapable shocks in its hammock, the patient found herself powerless

in the face of bereavement, some career failure, or seri-ous illness (Seligman,

Klein, & Miller, 1976). In both cases, the outcome is the same—a belief that

there’s no contingency between acts and outcomes, and so there’s no point in

trying.

Related Topics