Chapter: Biology of Disease: Cancer

Colorectal Cancer: Treatment, Signs, symptoms, diagnosis and staging

COLORECTAL CANCER

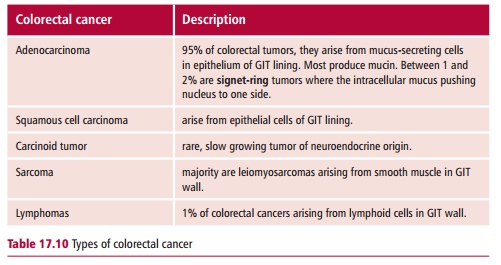

Colorectal cancer, otherwise known as bowel cancer, is one of the three most common cancers in men and women, both in the UK and in the USA. In the UK there are about 35 000 new cases each year, with a slight majority occurring in men. Approximately 60% of new cases are cancers of the colon while the remainder have cancers of the rectum. In the USA there are roughly 135 000 cases each year, about 70% being colon cancers. The five-year survival rate for colorectal cancer is 50–60%. The vast majority of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas and this section will concentrate on these. The remainder fall into several groups as shown in Table 17.10.

The risk factors for colorectal cancer include increasing age, a diet rich in fat and low in fiber, a history of inflammatory bowel disease and a hereditary predisposition. More than 80% are diagnosed in those aged over 60 years. A familial history of bowel cancer is also a strong risk factor as is the presence of polyps. A polyp is a benign tumor that arises from the epithelium of the GIT. Polyps range in size from a small bump to a lesion measuring 3 cm in diameter; most are asymptomatic.

Adenocarcinomas are known to originate from pre-existing polyps and the sequence of their development into a cancer is well documented. Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), a rare condition responsible for 1% of colorectal cancers, have a mutated form of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. This gene encodes a protein that degrades β -catenin, which activates growth-promoting oncogenes such as c-MYC. Mutations in APC lead to the production of inactive β -catenin, hence oncogenes are continuously activated. Patients with FAP are almost certain to develop colorectal cancer in middle age and they are recommended to have their colon removed by

The development of colorectal cancer is also associated with both hypomethylation and hypermethylation of DNA and this has been detected at the polyp stage. Methylation of DNA is involved in switching genes off, hence hypomethylation can result in activation of oncogenes, whereas hypermethylation could lead to inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Deletions in the long arm of chromosome 18 and in the short arm of chromosome 17 are also seen in colorectal cancers. Mutations in the RASgene have been detected in cells in the feces of patients with colorectal cancer and it is possible that this may be used as the basis for a noninvasive diagnostic procedure.

The condition, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is associated with inherited mutations in a number of genes involved in DNA repair that also predispose an individual to colon cancer. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer is estimated to cause between 2 and 5% of colorectal cancers and is linked to 40% of cases of colorectal cancer occurring in people below the age of 30 years. Other risk factors for colorectal cancer include being diabetic and being of Ashkenazi Jewish origin. This group also have a higher incidence of mutated BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and are therefore also more likely to develop breast cancer. The genetic link to colorectal cancer has not been fully elucidated.

Signs, symptoms, diagnosis and staging of colorectal cancers

Patients with colorectal cancer may present with symptoms that include loss of weight, bleeding from the rectum and/or blood in the feces, anemia resulting in fatigue and breathlessness, changes in bowel habits, including increased diarrhea, and pain in the abdomen. The tumor may cause a bowel obstruction and if this occurs the patient suffers abdominal pain, nausea and constipation. An initial detection of a lump in the abdomen or rectum means that the patient must be referred for further specialist examination. Colonoscopy is used to examine the whole colon and to obtain a biopsy for further investigation. An alternative to colonoscopy is flexible sigmoidoscopy, an endoscopic technique which examines only the lower part of the colon and the rectum. The concentration of CEA in the blood can be measured although increased values are not entirely specific for cancer and a poorly differentiated tumor may not produce CEA. This measurement may, however, be useful for monitoring disease progress and treatment. Abdominal CT scans are helpful in diagnosis of metastatic spread to the lymph nodes and liver, and chest X-rays are routinely used to detect metastases in the lungs. Prognosis is poor for patients with metastatic spread to these two organs.

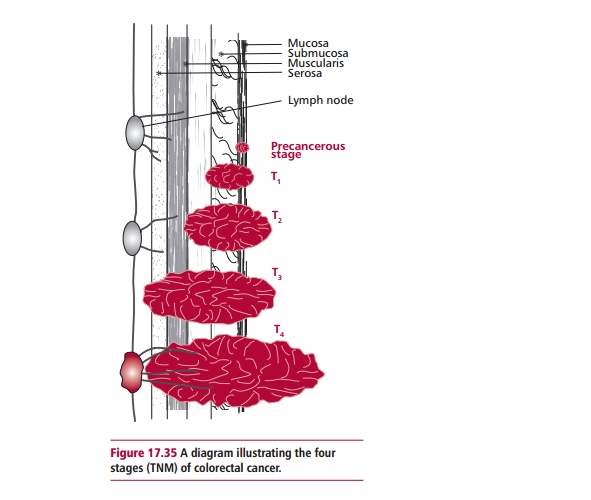

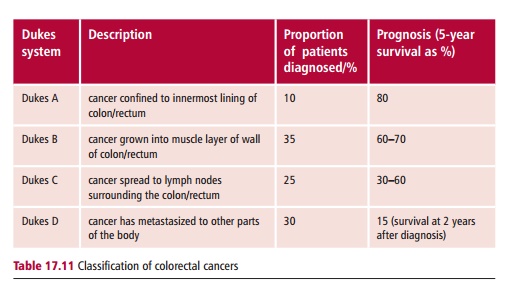

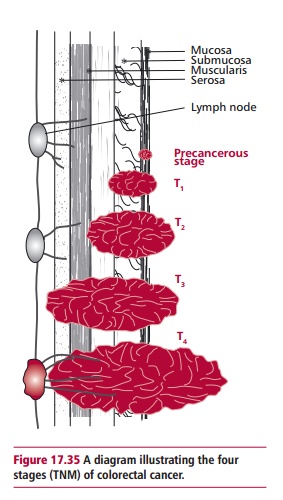

Several staging systems have been used for colorectal cancer. The Dukes system is shown in Table 17.11 which also documents the proportion of patients who present at this stage, together with the survival rates at five or two years.

The TNM staging system is also used increasingly for colorectal cancers (Figure 17.35). T1, T2 and T4 are equivalent to Dukes A, B and D respectively. T3 describes the situation if the tumor has broken the outermost membrane of the GIT. The lymph nodes are classified as N0 if there are none containing cancer cells, N1 where between one and three nearby lymph nodes are involved, and N3, where there are cancer cells in four or more lymph nodes that are more than 3 cm from the main tumor, or where there are cancer cells in lymph nodes connected to the main blood vessels around the GIT.

Treatment of colorectal cancer

The usual treatment for colorectal cancer is surgery. Various procedures may be used but, if possible, a resection, in which the length of GIT containing the tumor is excised and the two cut ends are stapled together to reinstate the integrity of the GIT, will be performed. The advantage of resection is that

Patients with rectal cancer may be given radiation treatment after surgery to reduce the risk of the tumor recurring locally. Radiation therapy may also be used in the palliative care of late stage metastatic cancer. Chemotherapy, 5-FU and leucovorin is sometimes offered postsurgery to patients with a Dukes B, and usually to those with Dukes C cancer. Chemotherapy of metastatic colorectal cancer uses 5-FU, leucovorin and irinotecan (CPT11). Combined oxaliplatin and 5FU treatment may also be used. Patients successfully treated for colorectal cancer should be regularly checked for several years after surgery to detect any recurrence of the tumor.

Related Topics