Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Sources of Psychiatric Ethics

Sources of Psychiatric Ethics

Law

Ethics and law are closely related, but they are

not synonymous (Ellis, 1991). Courts and legislatures attempt to embody

ethi-cal principles in their creation and interpretation of law. But not every

ethically supportable course of conduct is, or should be, codified in the form

of mandatory or prohibitory legal provisions backed up by the government’s

authority to punish, and not every legal mandate is consistent with medical

ethics.

Religion

It is beyond the scope to deal comprehensively with

the ethical codes established by the world’s various reli-gions. Suffice it to

say that many ethical decisions that confront psychiatrists have their roots in

religion. Indeed, almost to the end of the 19th century, the treatment of

mental disorders was conducted, to a great extent, under the auspices of

religious insti-tutions or at least in concert with the prevailing religious

ideas of the time. Today’s issues include treatment refusal, abortion and end

of life decisions, among many others. Psychiatrists must be sensitive to the

impact that their own and their patients’ religious beliefs have on their

understanding of human behavior.

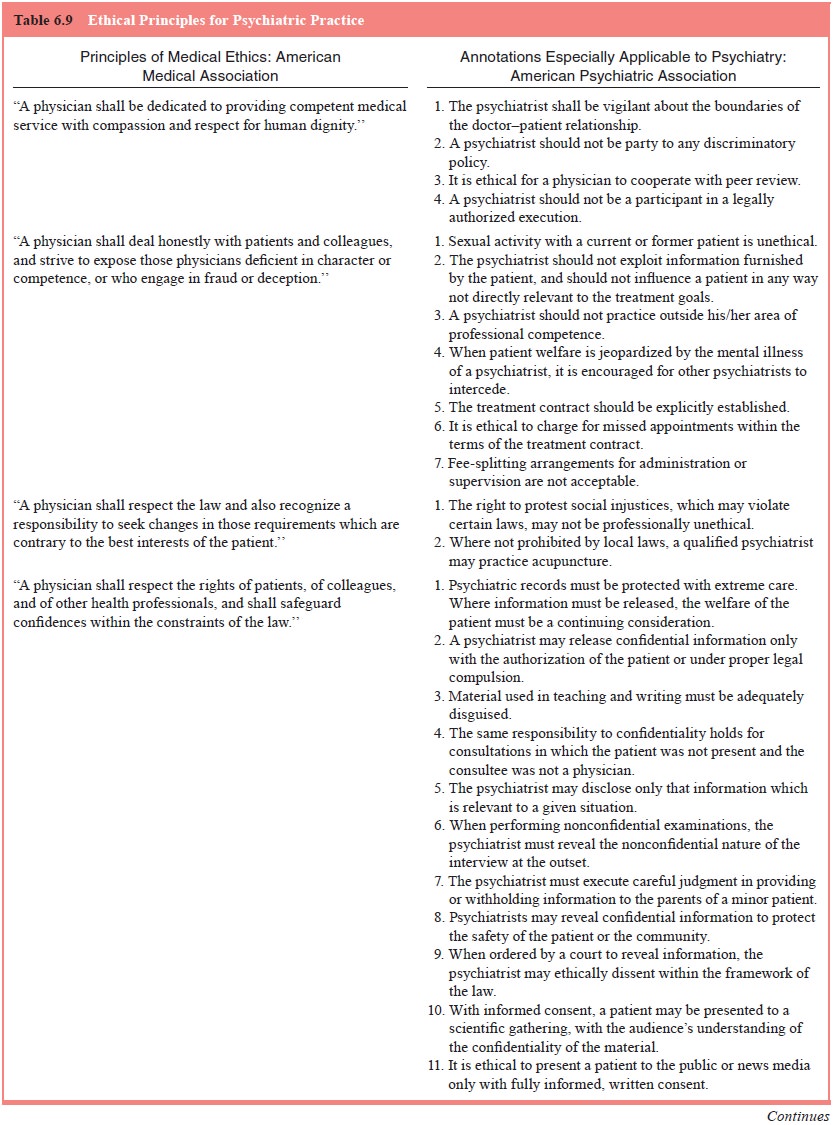

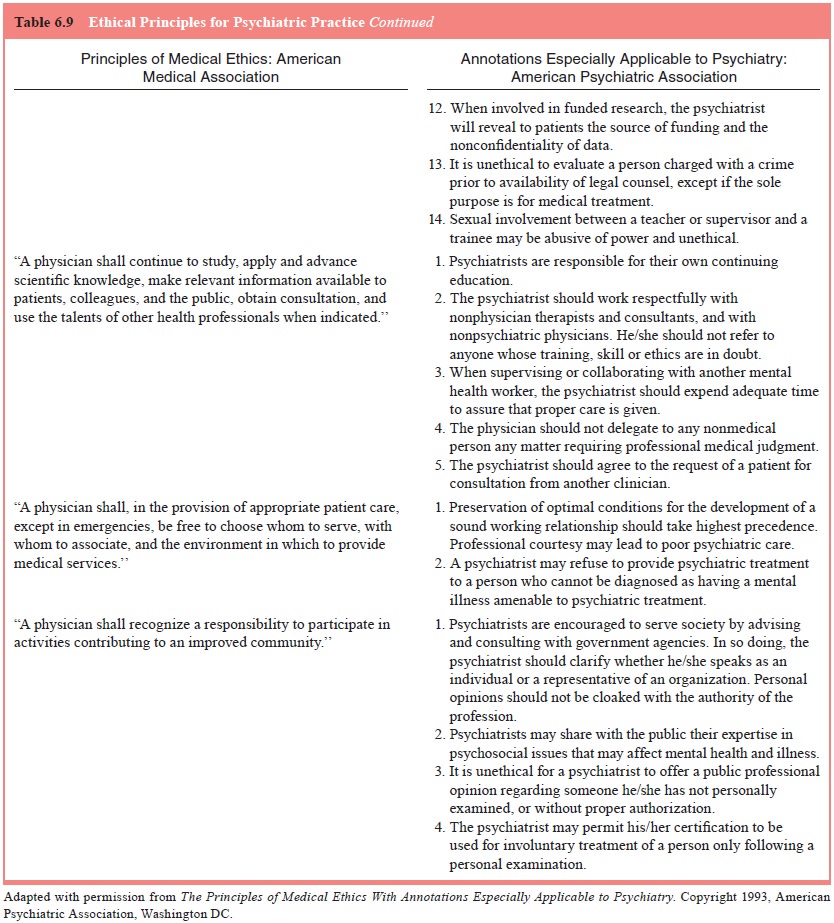

Professional Associations

One of the hallmark characteristics of a learned

profession is its development and adoption of a unique code of ethics to guide

its practitioners. The APA has adopted such a code since 1989. Although

“psychiatrists are assumed to have the same goals as all physicians’’, these

principles have been revised “with anno-tations especially applicable to

psychiatry’’. The rationale was that “there are special ethical problems in

psychiatric practice that differ in coloring and degree from ethical problems

in other branches of medical practice’’ (Table 6.9).

Related Topics