Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Competence, Capacity and Guardianship

Competence, Capacity and

Guardianship

Competence is best understood as a legal term

referring to an individual’s capacity to make informed decisions. Adult

indi-viduals are presumed to be legally competent, unless and until there is a

court finding of incompetence. A finding of incom-petence means that a physical

or mental illness has caused a defect in cognition or judgment, regarding the

specific area in question, such that the individual lacks the capacity to make

in-formed decisions. When a court determines that an individual is incompetent,

a guardian may be appointed to make decisions for that person.

Competence is often used as a general term, but it

should be defined specifically. With the advent of modern psychophar-macology,

competence in severely mentally ill patients is often related to medication

compliance. Even floridly psychotic pa-tients may become competent after they

are stabilized on medi-cations. Since the legal decision-making for incompetent

patients often involves determining what the individual would want if he or she

were competent to choose, it is important that the psychia-trist assess the

person’s capacity when he/she is doing clinically well, in addition to when he/she

is doing poorly.

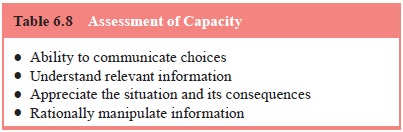

Assessing a patient’s capacity to give consent is

based on several general principles (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988). The patient

must be able to 1) communicate choices, 2) under-stand the relevant

information, 3) appreciate the situation and its consequences, and 4)

manipulate the information rationally (Table 6.8).

There is general agreement that the standard for

judging competence also varies with the presented task. For instance the

standard for competence to consent to take an experimental drug is higher than

for taking an aspirin. The greater the risk in the

intervention, the more the psychiatrist needs to be

clear about the four elements noted in the preceding paragraph.

Several other competencies require attention in

civil mat-ters. For example, testamentary capacity (the capacity to make a

will) may be challenged by disgruntled and disinherited par-ties. For this

reason, some people obtain an evaluation of their capacity to make a will

before their death. Testamentary capacity requires that individuals understand

1) the nature of a will, 2) the extent of their assets, 3) the identity of

their natural heirs, and 4) that they should not be under undue influence.

Decision-making can be based on either the “best interests’’ standard or the

“substituted judgment’’ model. The best interests model is a paternalistic

approach that assumes that decision-makers know what is in the patient’s best

interests, and that they will act ac-cordingly. It is a value laden paradigm

that requires guardians to be aware of their own value systems, and to be on

guard against the risk that their values may conflict with those that might

apply to the patient. Perhaps more onerous, but more individualized, is the

substituted judgment model, discussed briefly above in the section on informed

consent. Here, the guardian attempts to act in the manner the person would want

under the circumstances. This is a difficult task. When an individual has never

considered a possibility, such as being in a coma, it cannot be known with

certainty what the individual’s wishes would be. While it might be generally

agreed that individualized decision-making is a preferable model, it is easy to

see why the relative comfort of the best interest approach makes this model the

one that is most widely applied.

Related Topics