Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Exceptions to Informed Consent

Exceptions to Informed Consent

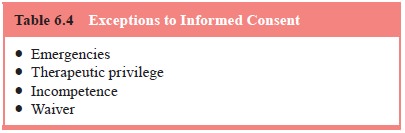

There are four primary exceptions to the general

rule that the pa-tient receiving treatment must give informed consent (Table

6.4). The first is a medical emergency. Consent is presumed when a person is

suffering from an emergent situation that requires treat-ment, but is unable to

give consent. Thus, for example, when a di-

abetic patient is in a coma and consent cannot be

obtained before giving the patient insulin, the treating physician may rely on

pre-sumed consent for treatment as a defense to a claim of battery. In

psychiatry, the definition of an emergency has been somewhat more ambiguous.

Because there is no national standard of what constitutes a psychiatric

emergency, clinicians should know the definitions (if any) in their state. They

should consider how emergent the situation is, document their assessment, and

note that it was not possible to gain the patient’s informed consent at the

time. Intervention in a psychiatric emergency, especially administration of

medication, is often not considered treatment in the same sense as emergency

treatment of a traditional medical condition. It is for this reason that many

states regulate adminis-tration of emergency psychiatric medications as

restraint, rather than as treatment.

Incompetence is the second exception to the need to

ob-tain informed consent from a patient. An incompetent person, by definition,

is incapable of giving informed consent; it can be granted only by that

person’s guardian, or other entity charged under state law with the authority

to give consent. (It is thus not truly an exception to the need for informed

consent, but a situa-tion in which the consent is obtained from a surrogate.)

Even in-competent patients should be engaged in the making of treatment

decisions, to the extent of their ability, and gaining their assent to

treatment is important, even if they do not have the legal capacity to render

informed consent. All states have procedures by which a person can be declared

incompetent; such a declaration usually requires a judicial finding, though

some states have administra-tive proceedings for resolving treatment issues

that do not require judicial intervention.

The third exception to informed consent arises from

the concept of therapeutic privilege. Psychiatrists use privilege when they

withhold information in the belief that giving a patient all of the information

necessary to make a decision would harm the patient. Invocation of therapeutic

privilege, rare in medicine, is even rarer in psychiatry, in which sharing

information is central to the work of the psychiatrist. Psychiatrists should

use this ex-ception to the informed consent doctrine exceedingly sparingly,

with extreme caution, and with great thought; here, the psychia-trist is taking

a maximally paternalistic posture in presuming what is not useful for a patient

to know. The psychiatrist assumes a grave risk of liability if the patient

suffers harm, and subse-quently proves that a reasonable patient would have

wanted to have the withheld information in order to make an informed choice

about treatment.

Waiver is the fourth exception in the informed

consent doctrine. Competent patients may request that their physicians not give

them information, effectively waiving their right to know. This circumstance

has become increasingly unusual over time as physicians are less likely to

withhold this information and patients less likely to request such a waiver.

Consent to the Treatment of Minors

Minors are considered to be incompetent for almost

all purposes, including the right to make medical decisions. Each state has its

own definition of the age that minors must attain to consent to different

treatments, and the age requirements may vary with the type of treatment. For instance,

a state may have a lower age of consent for treatment of sexually transmitted

diseases or mental illness than for traditional medical treatment.

Psychiatrists must become familiar with the law of the state or states in which

they practice.

Psychiatrists who work in schools must obtain the

consent of parents before initiating ongoing treatment. An emergency evaluation

of a student – performed without such consent – is permissible for the most

part under the doctrine of emergencies and must be documented as such (see

earlier discussion). Psychi-atrists who work in school settings also have to

work with parents who are separated or divorced. Psychiatrists are obligated to

de-termine which parent has legal custody and to obtain the consent of that parent

for the treatment of the child; documented proof of custody must be obtained.

Most states have laws by which minors may become emancipated, and therefore are

deemed competent to make their own decisions. The conditions of emancipation

typically include marriage, becoming a parent, entry into the armed services,

and sometimes a demonstrated ability of a minor to manage his or her own

financial affairs and to live on his or her own.

Related Topics