Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Confidentiality and Privilege

Confidentiality and Privilege

The principles of confidentiality and privilege

have a long and still evolving historical connection with the practice of

medicine and the role of the physician. The Hippocratic Oath states, “And about

whatever I may see or hear in treatment, or even without treatment, in the life

of human beings – things that should not ever be blurted out outside – I will

remain silent, holding such things to be unutterable [sacred, not to be

divulged]’’ (Von Staden, 1996). The elegant simplicity of this statement of principle

is now pitted against conflicting legal demands and societal values. The Tarasoff case (discussed below) and its

progeny, the increas-ing use of subpoenas for psychiatric records, the

complexity of interfacing with managed care, and confidentiality guidelines

related to human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) are just some of the

issues that complicate the psychiatrists’ oath of confidentiality.

Confidentiality

In the APA’s Principles

of Medical Ethics with Annotations Es-pecially Applicable to Psychiatry (1993),

Section 4, Annotation 1 reads,

“Confidentiality is essential to psychiatric treatment. This is based in part

on the special nature of psychiatric therapy as well as on the traditional

ethical relationship between physician and patient’’.

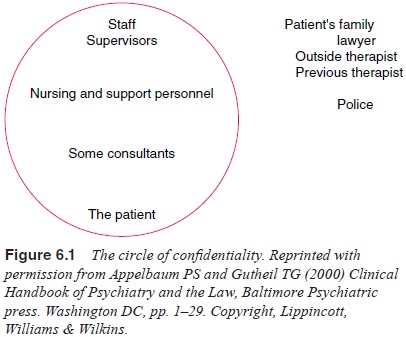

Appelbaum and Gutheil (2000) looked at practice in

psy-chiatric facilities, and devised the concept of a “circle of

confi-dentiality’’ (Figure 6.1). Within the circle, information about the

patient is shared without the patient’s consent. For instance, for a

hospitalized patient, the resident psychiatrist, the psychiatrist’s supervisor,

the staff and essential consultants are considered to be within the circle of

confidentiality. The patient’s family, the patient’s attorney, the patient’s

outside psychiatrist, the patient’s previous psychiatrist and the police are

outside the circle. As Appelbaum and Gutheil note, although the patient is

inside the circle, the patient may speak to anyone outside the circle without

restriction.

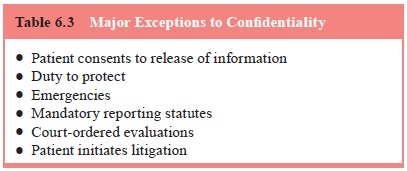

The duty of confidentiality is sometimes understood

in terms of the treatment contract between the patient and psy-chiatrist. There

is agreement between the legal system and the psychiatric profession that

confidentiality is not an absolute value. There are several major exceptions to

the obligation of

confidentiality, the most common of which is when

the patient consents to information being released. Psychiatrists and their

patients should be aware of the implications of releasing infor-mation to

insurance companies, family members, employers and so forth and should work

collaboratively in making these deci-sions (Table 6.3).

As a rule, the psychiatrist should get the

patient’s consent in writing and, optimally, the patient should read any

information that leaves the office before it is released.

The second exception is based on the duty to

protect, wherein the value of safety is given priority over the value of

confidentiality.

The third set of exceptions includes reporting

statutes, which mandate physician reporting of certain conditions. All states

have such laws in one form or another, and generally in-clude incidents of

infectious diseases, child abuse and elder abuse. If they are following any of

these statutes in good faith, psychiatrists run little risk of liability. See

the discussion of child abuse reporting, below.

The fourth set of exceptions includes emergencies.

For instance, when a psychiatrist is evaluating a patient in an emer-gency

department and the patient is grossly psychotic and unwill-ing to participate

in the interview, the psychiatrist is presented with the dilemma of whether to

contact family members or prior treaters without the expressed written consent

of the patient. This involves a risk–benefit assessment that the evaluating

psychiatrist must make. Psychiatrists must be aware of their states’ standards

concerning emergency breach of confidentiality; one state may require an

identifiable harm to be prevented, while another may permit breach when it is

necessary in the clinician’s judgment to gather the relevant information to

make a proper diagnosis or disposition for the patient.

Medical insurance has brought its own challenges to

the is-sue of confidentiality. Insurance companies may ask mental health

providers to sign a contract agreeing to release information to the insurer.

Patients may ultimately have to decide which they value more: their privacy or

the benefits obtained through the managed health company. Mental health

providers who are negotiating con-tracts with insurers should be mindful of any

obligation to provide confidential information without the patient’s consent.

Appelbaum and Gutheil (1991) state that

psychiatrists in the position of having to breach confidentiality should

observe certain basic principles. First, they should alert patients, whenever

pos-sible, of their intention to breach confidentiality before doing so.

Secondly, psychiatrists should use a hierarchy of confidentiality. Psychiatrists

do not need to jump to breach confidentiality in all situations where it is

necessary to communicate confidential in-formation. They often have time to

discuss issues with a patient, to consider alternatives and thus avoid such

confrontations. Finally, Appelbaum and Gutheil state that psychiatrists should

bear in mind that the alliance is based on the “healthy side’’ of the patient

against the patient’s illness. They suggested that when the patient is

expe-riencing impulses to harm another person, the psychiatrist and the patient

should attempt to make the call to warn the person together. The healthy side

of the patient is thus supported actively by the psy-chiatrist, as opposed to

having the psychiatrist “blow the whistle’’ on a patient who has become dangerous.

These recommendations emphasize the importance of the therapeutic alliance and

remind us that confidentiality is an important aspect of that alliance.

Psychiatrist–Patient Privilege

Privilege is defined as the patient’s right to

prevent testimony by a psychiatrist in a court setting (Gutheil, 1994;

Appelbaum and Gutheil, 1991). It rests on two primary justifications: 1) it

protects the patient’s interests in the privacy of treatment matters; and 2) it

may encourage patients to speak openly with their psychiatrists. The scope of

privilege is generally limited to the patient’s com-munications with the

psychiatrist. Observations of the patient’s demeanor, or his or her conduct or

even words in a public setting may not be covered within the privilege.

Privilege is a right belonging to the patient and

may be waived by the patient. Although the privilege does not belong to the

psychiatrist, he or she may have a duty to assert it in legal proceedings,

unless and until one of the exceptions to privilege applies. In the absence of

a release or waiver of privilege by the patient, psychiatrists should consult

with legal counsel if they are called to testify about their communications

with a patient.

Exceptions to the doctrine of privilege vary from

state to state and include situations when a patient has introduced his or her

mental state into litigation to which the patient is a party. In some states,

privilege does not apply in competence to stand trial, or criminal

responsibility evaluations. There are often exceptions in cases of child

custody, involuntary commitment proceedings, will contests, or malpractice

claims filed by the patient against a psychiatrist. Finally, state law may vary

on the scope of the exception once it is invoked.

Related Topics