Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Rights and Responsibilities

Rights and Responsibilities

Right to Treatment

Although the US Supreme Court has expounded no

national, con-stitutionally based right to treatment, there has been a

substantial amount of activity in this area since Birnbaum published “The Right

to Treatment’’ in 1960. At the time the article was published, it was common

for psychiatric patients to spend decades in hospi-tals, at times

involuntarily, while receiving little treatment or only custodial care. The

article attempted to upgrade the quality of care in hospitals by creating a

hospitalization-treatment quid pro quo. Birnbaum (1965) later criticized state

hospital conditions, declar-ing that “Personally, I should like to state that

as a doctor I often find it repugnant to use the term ‘patient’ to describe persons

in certain mental hospitals’’. He instead argued that “inmate’’ was a better

term if no treatment were given. Birnbaum’s landmark ar-ticles generated

interest in this key area of mental health policy.

Birnbaum’s quid pro quo rationale was endorsed in Rouse v. Cameron (1966) decided by Judge Bazelon of the District of Columbia Circuit Court. Rouse was found not guilty by reason of in-sanity on a misdemeanor charge and was thereafter civilly committed to St Elizabeth’s Hospital. He petitioned for his release based on the argument that he was not receiving treatment. Judge Bazelon ruled that hospitals must make real efforts to improve patients’ conditions and that lack of resources was not an adequate defense. In his decision he wrote, “The hospital need not show that the treatment will cure or improve him but only that there is a bona fide effort to do so’’.

The case of Wyatt

v. Stickney (1972), a class action suit against an Alabama hospital with

poor conditions for patients, led to definitions of humane environment, which

have been incorporated into a patient’s bill of rights in many states. Chief

Judge Johnson wrote for the US District Court, “[Involuntarily committed

patients] unquestionably have a constitutional right to receive such individual

treatment as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to

improve his or her mental condition’’. Although this case was not heard by the

US Supreme Court, it did have far-reaching social consequences for

institu-tions in that it prompted scrutiny of the services they provide.

It was not until 1982, in the case of Youngberg v. Romeo (1982), that the

Court held that a person who is involuntarily con-fined has a right to

“minimally adequate training’’. Romeo was a profoundly retarded man who

suffered injuries “on at least 63 occasions … by his own violence and by the

reactions of other residents to him’’ while he was an inpatient at Pennhurst

State Hospital in Pennsylvania. His mother sued, arguing that Romeo’s Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendment rights were being violated. The US Supreme Court

agreed that Romeo had “constitutionally protected liberty interests under the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to reasonably safe conditions of

confine-ment, freedom from unreasonable bodily restraints, and such minimally

adequate training as reasonably may be required by these interests’’.

“Minimally adequate training’’ required the ex-ercise of professional judgment,

which was held to be presump-tively valid and to which “courts must show

deference’’.

Most of the right to treatment cases attacked

institutional standards of care, and were based on efforts to expand the scope

of constitutional rights of inpatients. As will be seen below, cur-rent

litigation seeking to establish rights to treatment in the com-munity focuses

largely on the statutory rights afforded by such anti-discrimination statutes

as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Right to Refuse Treatment

Patients with little or no insight into the nature

of their psychiat-ric illness often refuse treatment. A compelling set of

ethical and legal questions arises when a person’s stated choice (not to

re-ceive treatment) appears to conflict with medical prediction that the

person’s insight and mental status would probably improve with treatment. In

the past, a general assumption that mentally ill patients were, by definition,

incompetent, led society to grant psychiatrists a great deal of autonomy in

selecting and adminis-tering treatments to patients. With the consumer activism

of the 1960s and 1970s and the accompanying development of patients’ rights,

however, psychiatrists and legal authorities have come to see that

involuntarily committed patients are not always glob-ally incompetent, and

efforts to support patients’ rights to refuse treatment have increased.

Although the US Supreme Court has not declared a

federal right to refuse treatment, federal Appeals Courts and most state courts

have found such rights in the federal or state constitutions, citing the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, within the right to privacy, bodily

integrity, or per-sonal security.

Appelbaum (1988) has described two broad models of

treatment refusal. The “rights-driven’’ model seeks to maximize patient

autonomy. It is based on the principle that competent adults have the right to

reject treatment, even if the rejection of such treatment may result in harm or

even death. States that adopt this model focus on the patient’s competence to

make the decision and often have considerable judicial procedures protecting

patients. The laws of these states typically remove decision-making power from

the psychiatrist and vest it in a guardian or the court. In these states the

guardian or court decides what the patient would want if he or she were

competent (the “substituted judgment’’ standard). The substituted judgment

doctrine requires a challenging deci-sion: it means that the judicial

decision-maker must decide, based not on his or her own values and interests,

or even on what may objectively be in the patient’s best interests, but instead

on what the patient would decide if he or she were competent.

The “treatment-driven’’ model tends to view

treatment as an essential element of commitment to a hospital. States with this

model tend to give psychiatrists more autonomy in making decisions for

patients. Procedural review is done primarily by psychiatrists and is usually

focused on whether the treatment is appropriate to the patients’ conditions. A

series of cases ema-nating from Massachusetts is emblematic of the

rights-driven model. In the matter of Guardianship

of Richard Roe III (1981), the court noted on involuntary psychiatric

medication for psychi-atric outpatients, stating, “If an incompetent individual

refuses antipsychotic drugs, those charged with his protection must seek

judicial determination of substituted judgment’’.

A later Massachusetts case, Rogers v. Commissioner of Mental

Health (1983), applied this rationale to involuntary inpa-tients.

Incompetent patients at Boston State Hospital were being given antipsychotic

medication without the opportunity to give informed consent. The Rogers case

upholds the right of com-mitted mentally ill patients to make treatment

decisions unless they have been adjudicated incompetent by a court. The Rogers

court also affirmed the holding that treatment with antipsychotic medication

constituted extraordinary treatment, and that author-ity to administer such

medication to an incompetent individual required the exercise of the

individual’s substituted judgment. The court outlined six factors that a judge

must assess when de-termining whether a patient should be permitted to refuse

treat-ment: 1) the patient’s previously expressed preference; 2) the patient’s

religious convictions; 3) the impact on family of the patient’s preference; 4)

probable side effects; 5) prognosis with treatment; and 6) prognosis without

treatment. Several cases il-lustrate the treatment-driven model. Rennie v. Klein (1983), de-cided in the

Third Circuit of the US Court of Appeals, held that New Jersey’s procedures for

reviewing the administration of antipsychotics to an unwilling patient were

consistent with due process: the “decision to administer such drugs against a

patient’s will must be based on accepted professional judgment’’. Rather than

have the courts superimpose procedural safeguards, treat-ment-driven model

cases defer to medical judgment. The Rennie decision relied on the US Supreme

Court’s deference to profes-sional judgment in Youngberg v. Romeo (1982).

Liberty and Civil Commitment

Although it is generally agreed that patients have

a right to be treated in the least restrictive setting, there are times when a

person’s mental illness is such that he or she must be

hospitalizedinvoluntarily. Each state has different provisions for short-term

emergency commitment. Many states have removed this process from the judicial

setting; some states, however, require a prob-able cause hearing before even an

emergency commitment. The purpose of such a hearing is to determine whether

there is prob-able cause to believe that the person meets the legal criteria

for involuntary hospitalization. If the patient is hospitalized after such a

hearing, it is generally for a short period of time for evalu-ation; if it is

determined that the patient needs longer involuntary hospitalization, then the

statutory procedures for long-term com-mitment must be followed.

In the case of O’Connor

v. Donaldson (1975), the US Supreme Court set a minimum below which states

cannot set their standards for civil commitment. The Court wrote: “The state

cannot constitutionally confine without more, a nondanger-ous, mentally ill

person who is capable of surviving safely by himself or with the help of family

or friends’’. While the Court did not state what it meant by “more’’, most

states now require a finding of dangerousness in addition to mental illness.

In Addington

v. Texas (1979), the US Supreme Court recog-nized the substantial liberty

interest involved in a commitment, and set the minimum standard of proof for

commitment cases as “clear and convincing’’. The court ruled: “The individual’s

lib-erty interest in the outcome of a civil commitment proceeding is of such

weight and gravity, compared with the state’s inter-ests in providing care to

its citizens who are unable, because of emotional disorders, to care for

themselves…that due process requires the State to justify commitment by proof

more substan-tial than mere preponderance of the evidence…. The reasonable- doubt

standard is inappropriate in civil commitment proceedings because, given the

uncertainty of psychiatric diagnosis, it may impose a burden the state cannot

meet and thereby erect an un-reasonable barrier to needed medical treatment’’.

(A few states do interpret their own constitutions to require proof beyond a

reasonable doubt.)

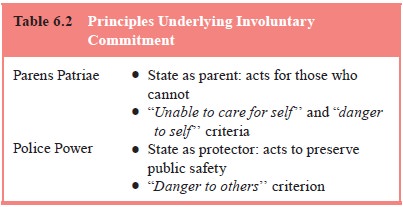

The standards for long-term commitment vary from

state to state, but they all rely on two broad principles of state power. One

is the parens patriae power; the

other, the police power. Parens patriae, translated from Latin as

“father of the country’’, histori-cally referred to the sovereign’s power to

make decisions for the subjects. A more contemporary translation is “state as

parent’’, which refers to the government’s interest in, and responsibility to

act for, individuals who are unable to care for themselves. Parens patriae is used as a rationale for commitment when a person is unable to care for herself or himself

as a result of a mental ill-ness or when he or she poses a danger to self. The

police power stems from the state’s interest in maintaining public safety. The

commitment criterion of “dangerousness to others’’ is derived from the police

power. Over time, the trend in legislation and in court action has been more

toward the dangerousness standard and less toward disability. Under all current

statutes, a finding of mental illness is a prerequisite to commitment Table

6.2.

The notion of dangerousness to others or to self is

a prob-lematical one for psychiatrists, given that prediction of harm is an inexact

science. Complicating the picture is the fact that states also require

different levels of proof that people are dangerous to themselves. Some states

require imminent harm, while oth-ers are more tolerant of general predictions

of future dangerous-ness based on a patient’s pattern of treatment

noncompliance and decompensation.

Finally, many states require a finding that

hospitalization is the least restrictive method to prevent the harm the patient

faces. In Lake

v. Cameron (1966), the District of Columbia Court of Appeals held that a

60-year-old demented homeless woman could not be involuntarily hospitalized if

there were other alter-natives. This case is most famous for the concept of

“least restric-tive alternative’’, as it focused on the place of confinement as

well as the fact of confinement.

The issues underlying the threshold for commitment

are fundamentally social, not psychiatric. They entail a balancing of rights

and liberty interests with needs for treatment and safety. This balance has

historically shifted with changes in the political and social climate, and

continues to be a source of debate in both the legal and mental health fields.

In 1985, the APA developed a Model Law for

Commitment, which generated considerable debate in the profession: “[I]t was

conceived in response to the…‘libertarian model,’ which many mental health

professionals and growing numbers of families be-lieved was unworkable,

unrealistic and inhumane’’ (Stone, 1985). Stone added that “the liberty of psychotic

persons to sleep in the streets of America is hardly a cherished freedom’’ and

advocated for greater discretion for psychiatric commitment as well as greater

resources for treatment once the patient is hospitalized.

Outpatient Commitment

Progress in the treatment of severe and chronic

mental illness often depends upon the patient’s compliance with medication and

other treatment regimens in the community. This has been a source of challenge

and frustration for psychiatrists who treat such patients. In recent years

there has been a growth of interest in the possibility that outpatient

commitment may offer a way to ensure that those who most need treatment will in

fact receive it. In principle, an outpatient commitment law allows the same

sort of treatment options as already exist with inpatient commit-ment: a

patient may be deprived of liberty and, if found to be incompetent to make

medication decisions, may be made to take medication against his will. While

inpatient commitment is justi-fied when a patient represents a danger or cannot

care for himself, how does one justify coercing a patient who may be stable,

rela-tively symptom-free and functioning in the community?

Here the legal debate splits into two camps. Those

in fa-vor of outpatient commitment make several arguments: 1) the treatments

are safe and effective; 2) untreated mental illness may increase the likelihood

of violence, homelessness, incarceration and suicide; and, more

controversially, 3) patients with severe mental illness frequently lack

awareness of their condition, and are therefore not really free when ill

(Torrey and Zdanowicz, 2001). Those opposing outpatient commitment counter

that:

better funded and staffed outpatient programs would

provide the kind of outreach which would make coercion unnecessary; 2) the

prospect of coercion may actually drive certain patients away from help; 3)

public safety would not be enhanced by outpatient commitment; and 4) even the

most ill patient is, in the eyes of the law, still competent to refuse treatment

(Allen and Smith, 2001).

At least 41 states permit some form of outpatient

com-mitment, yet the first two randomized trials examining its use (Steadman et al., 2001; Swartz et al., 2001) provided equivocal

evidence of efficacy (Appelbaum, 2001). The actual mechanics of apprehending a

nondangerous person, taking him/her to some facility, and injecting him/her

involuntarily with medication, all because he/she had not followed through on a

treatment plan, has proven difficult both to implement and to tolerate in a

society which still places great value on maintaining its citizens’ liberty

interests. The debate will continue as psychiatrists try to reduce the

aggregate suffering imposed on individuals and society by the effects of

untreated mental illness.

Related Topics