Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Liability for Supervising Other Professionals

Liability for Supervising Other

Professionals

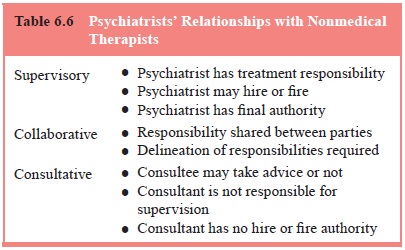

Psychiatrists work in a variety of settings and

interact in many different ways with other mental health professionals. One

as-pect of this interaction is the liability potential that psychiatrists

undertake in each of these relationships. The APA publication entitled

“Guidelines for psychiatrists in consultative, supervi-sory, or collaborative

relationships with nonmedical therapists’’ (1980) outlines the typical

consultative relationships and their corresponding degree of responsibility.

Broadly, the degree of li-ability correlates with the extent of authority to

make (as opposed to recommend) treatment decisions (Table 6.6).

Supervisory relationships are relationships in

which the psychiatrist is hierarchically and legally responsible for the

overall care of the patient, and will be held responsible for the treatment

provided by those he or she supervises. The American Psychiatric Association

(1980) guidelines state that:

In a supervisory relationship the psychiatrist

retains direct re-sponsibility for patient care and gives professional

direction and active guidance to the therapist. In this relationship the

non-medical therapist may be an employee of an organized health care setting or

of the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist remains ethi-cally and medically

responsible for the patient’s care as long as the treatment continues under his

or her supervision. The pa-tient should be fully informed of the existence and

nature of, and any changes in, the supervisory relationship.

Consultative relationships are different in terms of the level of responsibility and liability undertaken. Consultative ad-vice is given on a “take it or leave it’’ basis. Consultants are out-side the decision-making chain of command; they do not make treatment decisions, and do not have hiring and firing authority. As such, they generally are not held liable for treatment deci-sions (though psychiatrists practicing as consultants should be aware of any unusual legal provisions in the state in which they practice). The American Psychiatric Association (1980) guide-lines state that in this type of relationship the psychiatrist does not assume responsibility for the patient’s care. The psychiatrist evaluates the information provided by the therapist and offers a medical opinion which the therapist may or may not accept. Con-sultation is not a one-way process and psychiatrists do and should seek appropriate consultation from members of other disciplines in order to provide more comprehensive services to patients.

Risk Management Techniques

There is consensus among risk management experts

that various strategies can reduce medico–legal liability. The clinical

strate-gies of obtaining consultation on difficult cases, documenting the

rationale behind critical decisions, and using informed consent to build

rapport are valuable risk management techniques. In docu-mentation, “thinking

for the record’’ is advocated by Gutheil. The psychiatrist thus demonstrates

the use of judgment and ongoing risk benefit assessments. Institutional

strategies include regular quality assurance monitoring, training in

documentation, a sys-tem for working with patients and families on adverse

effects, and providing access to expert consultation.

In psychiatry, several areas deserve special

mention. Sui-cide and attempted suicide represent one of the most common and

expensive sources of lawsuits in psychiatry (Slawson, 1989). Psychiatrists

should assess the level of suicidality and the ability of patients to monitor

and report their suicidality (Gutheil et

al., 1986) and plan an appropriate strategy based on that assessment. In

lawsuits involving suicide, the patients are more commonly portrayed as the

victims, rather than agents in their own deaths. The psychiatrist who both

fosters and documents active col-laboration with the patient demonstrates good

risk management practice as well as clinical skill. Prescribing medications

also raises psychiatrists’ liability risk. Solid documentation of his-tory,

examinations, laboratory tests, indications for a medication and risk

assessment are essential to reduce liability. Consultation with a colleague

should be sought for difficult cases.

Duty to Warn, Duty to Protect

When a psychotherapist determines (or, pursuant to

the stand-ards of the profession, should determine) that his/her patient

represents a serious danger of violence to another, he/she incurs an obligation

to use reasonable care to protect the intended vic-tim against such danger. The

discharge of such duty, depending on the nature of the case, may call for the

therapist to warn the intended victim or others likely to appraise the victim

of the danger, to notify the police, or to take whatever other steps are

reasonably necessary under the circumstances.

This is the so-called Tarasoff principle,

established by California Judge Tobrinen in 1976 in the case of Tarasoff v. Regents (1976). It has generated controversy, spawned lawsuits, and initiated a fundamental

reexamination of the psychiatrist’s role vis-à-vis

members of the public.

The Tarasoff

case involved the tragic death of a Univer-sity of California student, Tatiana

Tarasoff, who was murdered by a fellow student, Prosenjit Poddar. Poddar was an

outpatient at the campus mental health clinic. He stated to his psycholo-gist

that he intended to kill Tarasoff. The therapist completedpaperwork to have

Poddar committed for 72-hour emergency psychiatric detention. The local police

detained Poddar, but re-leased him when he stated that he would “stay away from

that girl’’. Two months later he successfully carried out his threat to kill

Tarasoff.

This case, as well as subsequent cases and

legislation in other states, created new clinical and ethical dilemmas for

psy-chiatrists, as they now must balance confidentiality with the safety of

third parties in outpatient settings as well. At what point is the inherently

trusting nature of the psychiatrist–patient relationship impaired by the

legally driven obligation to report threats of harm? When should a psychiatrist

report a patient’s vague statement wishing to harm a third party? How should

the patient’s violent history be weighed in the assessment of whether to

violate confidentiality? Does the circle of responsibility in-clude only named

third parties, or does it extend to groups of reasonably identifiable potential

victims? Is a warning sufficient? Although these questions are ultimately

matters of clinical judg-ment, psychiatrists need to know whether their states

have estab-lished specific guidelines for settling them.

Related Topics