Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Law, Ethics and Psychiatry

Criminal Law and Psychiatry

Criminal Law and Psychiatry

The psychiatrist’s role in the courtroom is

substantially different from that in the clinical setting (Rappeport, 1982). In

criminal cases, psychiatrists are commonly called on to evaluate defen-dants’

competence to stand trial or (less commonly) criminal responsibility. In

perhaps the most challenging of situations, psy-chiatrists are faced with the

ethically challenging task of evaluat-ing defendants’ competence to understand

the death penalty.

The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness

Psychiatrists may work in forensic settings as

agents of the court, providing impartial evaluations for the judge, or may

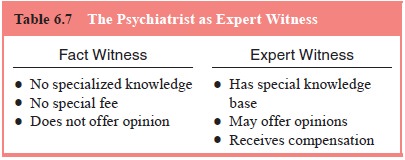

function as experts for the defense or prosecution. As opposed to fact

wit-nesses, who can testify only as to facts that they have observed, expert

witnesses may review records, conduct tests, perform evaluations or other

research, and provide opinions (such as di-agnoses) in court. Expert witnesses,

by definition, are familiar with a body of professional knowledge that is not

well known to the layperson (Table 6.7).

When asked to serve as an expert witness, the

psychiatrist should have a clear understanding of the legal question or

stan-dard being addressed. The expert witness should inform the client that

patient–psychiatrist confidentiality is not to be expected and that the

information being elicited will be presented to the court to help the judge or

jury make a decision. In general, attorneys attempt to establish the

credibility of their experts by presenting their qualifications to the court,

either by testimony, or by ad-mitting the expert’s resumé. Psychiatrists who

offer themselves as expert witnesses should be prepared to have their

credentials challenged by the attorney for the opposing side. Good expert

witnesses take these challenges in stride. They

respond to ques-tions calmly, without becoming defensive or arrogant. Good

ex-pert testimony is given in understandable, jargon-free language, with short,

concise answers. Expert testimony is a challenging and difficult professional

task.

Competence to Stand Trial Evaluations

In order for a criminal case to proceed, the

defendant must be competent to stand trial. This is a constitutional standard

that has its roots in old English law. Although specific standards of

competence are determined on a state-by-state basis, the federal standard has

provided the basis for each state’s law. The test is “whether [the defendant]

has sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable

degree of rational understand-ing and whether he has a rational as well as a

factual understand-ing of the proceedings against him’’ (Dusky v. United States, 1960).’’ The legal standard is not an

exacting one. Only a small proportion of criminal defendants are referred for

competency evaluations.

Although there is no universally accepted clinical

standard for assessing competence, the McGarry (McGarry et al., 1973) criteria have been empirically validated and are the

most com-monly used sources of evaluation. This standard encourages the

psychiatrist to assess 13 different areas of functioning, including the

patient’s behavior, ability to relate to an attorney, ability to plan a legal

strategy, and motivation and capacity to testify, in addition to the patient’s

understanding of the charges, possible consequences, and likely outcomes.

Psychiatrists must remember that when they are

conduct-ing evaluations on behalf of the court, they are agents of the court;

the usual rules of the psychiatrist–patient relationship (including

confidentiality and privilege) are thereby waived. Those being examined must be

informed of these different ground rules, in accordance with the requirements

of the particular state. Since the defendant’s understanding of his or her

waiver of confiden-tiality is often an issue, the evaluator should carefully

document the defendant’s response to the information, using direct quotes, when

possible. States have different requirements in cases where the patient appears

incompetent to give informed consent for a “stand trial’’ evaluation. The

psychiatrist needs to be aware of these requirements, and to be prepared to

proceed accordingly (some states permit the evaluation to proceed; others might

re-quire further hearings). The fate of defendants found incompe-tent to stand

trial was addressed in Jackson v. Indiana

(1972). Jackson was mentally retarded, deaf and mute; he was charged with two

counts of petty larceny. The psychiatrist who evaluated Jackson concluded that

he was almost completely unable to com-municate; in addition to his lack of

hearing, his mental deficiency left him unable to understand the nature of the

charges against him or to participate in his defense. Based on this evidence,

the trial court found that Jackson “lacked comprehension sufficient to make his

defense’’ and ordered him committed to the Indiana Department of Mental Health

until that department could certify to the court that he was “sane’’.

Since it was clear that Jackson would never become

“sane’’, (that is, competent to stand trial), his commitment es-sentially

amounted to imposition of a life sentence, without his ever being convicted of

a crime. The court held that this outcome violated Jackson’s Fourteenth

Amendment right to due process and that a defendant cannot be committed

indefinitely just be-cause he is incompetent to stand trial. His commitment

must be for a purpose permitted under state law (and the Constitution).

Thus, if the defendant may reasonably be restored

to competence with treatment, he may be committed for that purpose. If it is

unlikely that the defendant will be restored to competence (as in Jackson’s

case), then his commitment must meet other legitimate state purposes, such as

prevention of harm under civil commit-ment standards. If the defendant does not

meet the criteria for such a commitment, he must be released.

Insanity Defense

There is an important distinction between a finding

of incom-petence to stand trial and a finding of not guilty by reason of

insanity (NGRI). The former means that defendants do not have a chance to

defend themselves until competence is restored. The latter is a not guilty

finding, based on the defendant’s inability to have formed the state of mind

requisite for a criminal con-viction. It is not a matter of restoration or

recovery from men-tal illness; once a defendant is found NGRI, the criminal

case is permanently resolved. Criminal responsibility and competency

evaluations are often requested together, but they are separate and distinct.

In order to be convicted, a defendant must be shown

both to be guilty of committing an illegal act (actus reus) and to have had the intention of committing the crime (mens rea). Criminal responsibility

evaluations focus on the mens rea

component of criminal acts. The psychiatrist involved in an insanity defense is

presented with a more challenging assignment than that of the competence to

stand trial evaluation. Assessing a patient’s men-tal state retrospectively is

a task fraught with difficulties. The de-fendant may forget, lie, or “fill in’’

details of the events. For this reason, this evaluation typically involves more

collateral inves-tigation, such as reviewing the prosecutor’s file including

police, witness, victim and perhaps even autopsy reports, in addition to

standard history such as past psychiatric records. The clinical interview

should include the confidentiality warning, a detailed present-day mental

status examination, and direct queries into the defendant’s recollected mental

state and in-depth recall of the crime. This detective work, together with

careful questioning, as well as psychological or neurological assessment when

indicated, is necessary to enable the psychiatrist to present as clear a

picture as possible of the defendant’s state of mind at the moment of the

crime.

The first appellate decision in English law

involving the in-sanity defense was M’Naghten’s

case. In 1843, Daniel M’Naghten shot and killed Edward Drummond, who was

secretary to the prime minister. Apparently, M’Naghten was under the delusion

that he was being persecuted by the prime minister as well as other people

throughout all of England. After this case, the stan-dard for criminal

responsibility became known as the M’Naghten rule: “To establish a defense on

the grounds of insanity it must be conclusively proved that, at the time of

committing the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of

reason, from the disease of the mind, as to not know the nature and quality of

the act he was doing; or if he did know it that he did not know what he was

doing was wrong’’. This standard allows either a cognitive test (did he know

what he was doing?) or a moral test (did he know it was wrong?). It addresses

itself to the specific criminal act, as opposed to assessing the defendant from

the per-spective of a broad-reaching sense of right and wrong.

The American Law Institute standard provides: “A

person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such con-duct

as a result of a mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either

to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct orto conform his conduct to the

requirements of the law’’ (Model Penal Code, 1955). This test incorporates the

cognitive compo-nent of the M’Naghten rule but, by use of the terms “mental

dis-ease or defect’’, allows for the possibility that conditions other than

psychotic illnesses (such as impulse disorders) may result in a lack of

criminal responsibility. Contrary to public perception, a successful insanity

defense does not usually result in freedom. In fact, when a defendant is found

not guilty by reason of insanity, he or she may face years of confinement in a

hospital setting. As Elliot and colleagues (1993) note:

Acquittals by reason of insanity are unlike

acquittals in crimi-nal law. The criminal defendant who wins an outright

acquittal is free of state control and may simply walk away from the court

house after the trial. But the defendant found [NGRI] typically remains

confined….

The hurdles to commitment are typically much lower

and the barriers to release much higher. Especially when charged with

misdemeanors, insanity acquittees generally remain hospitalized far longer than

ordinary civil acquittees and may remain con-fined for periods greater than the

maximum sentence that would have been possible on conviction of the criminal

charges.

Related Topics