Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Fluid and Electrolytes: Balance and Distribution

Sodium Excess (Hypernatremia)

SODIUM

EXCESS (HYPERNATREMIA)

Hypernatremia is a higher-than-normal serum sodium level (ex-ceeding 145

mEq/L [145 mmol/L]) (Adrogue & Madias, 2000a). It can be caused by a gain

of sodium in excess of water or by a loss of water in excess of sodium. It can

occur in patients with normal fluid volume or in those with FVD or FVE. With a

water loss, the patient loses more water than sodium; as a result, the serumsodium concentration

increases and the increased concentration pulls fluid out of the cell. This is

both an extracellular and intra-cellular FVD. In sodium excess, the patient

ingests or retains more sodium than water.

Pathophysiology

A common cause of hypernatremia is fluid deprivation in uncon-scious

patients who cannot perceive, respond to, or communicate their thirst (Adrogue

& Madias, 2000a). Most often affected in this regard are very old, very

young, and cognitively impaired patients. Administration of hypertonic enteral

feedings without adequate water supplements leads to hypernatremia, as does

wa-tery diarrhea and greatly increased insensible water loss (eg,

hyper-ventilation, denuding effects of burns).

Diabetes insipidus, a

deficiency of ADH from the posterior pituitary gland, leads to hypernatremia if

the patient does not ex-perience, or cannot respond to, thirst or if fluids are

excessively restricted. Less common causes are heat stroke, near-drowning in

sea water (which contains a sodium concentration of approxi-mately 500 mEq/L),

and malfunction of either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis proportioning

systems. IV administration of hypertonic saline or excessive use of sodium

bicarbonate also causes hypernatremia.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of hypernatremia are primarily neuro-logic

and are presumably the consequence of cellular dehydration (Adrogue &

Madias, 2000a). Hypernatremia results in a rela-tively concentrated ECF,

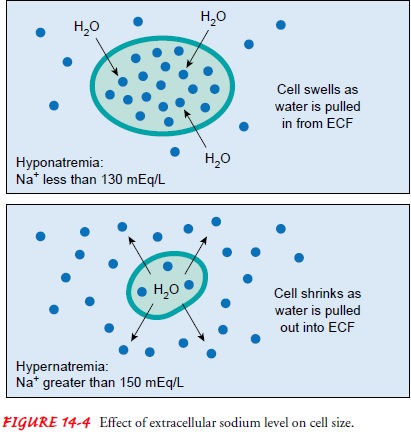

causing water to be pulled from the cells (see Fig. 14-4). Clinically, these

changes may be manifested by restlessness and weakness in moderate

hypernatremia and by dis-orientation, delusions, and hallucinations in severe

hypernatremia. Dehydration (resulting in hypernatremia) is often overlooked as

the primary reason for behavioral changes in the elderly patient. If

hypernatremia is severe, permanent brain damage can occur (especially in

children). Brain damage is apparently due to sub-arachnoid hemorrhages that

result from brain contraction.

A primary characteristic of hypernatremia is thirst. Thirst is so strong

a defender of serum sodium levels in healthy people that hypernatremia never

occurs unless the person is unconscious or is denied access to water.

Unfortunately, ill people may have an impaired thirst mechanism. Other signs

include a dry, swollen tongue and sticky mucous membranes. Flushed skin,

peripheral and pulmonary edema, postural hypotension, and increased mus-cle

tone and deep tendon reflexes are additional signs and symp-toms of

hypernatremia. Body temperature may rise mildly but returns to normal when the

hypernatremia is corrected.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

In hypernatremia, the serum sodium level exceeds 145 mEq/L (145 mmol/L)

and the serum osmolality exceeds 295 mOsm/kg (295 mmol/L). The urine specific

gravity and urine osmolality are increased as the kidneys attempt to conserve

water (provided the water loss is from a route other than the kidneys) (Fall,

2000).

Medical Management

Hypernatremia treatment consists of a gradual lowering of the serum

sodium level by the infusion of a hypotonic electrolyte so-lution (eg, 0.3%

sodium chloride) or an isotonic nonsaline solution(eg, dextrose 5% in water [D5W]). D5W is indicated when water needs to be replaced without sodium. Many

clinicians consider a hypotonic sodium solution to be safer than D5W because it al-lows a gradual reduction in

the serum sodium level and thereby decreases the risk of cerebral edema. It is

the solution of choice in severe hyperglycemia with hypernatremia. A rapid

reduction in the serum sodium level temporarily decreases the plasma

osmo-lality below that of the fluid in the brain tissue, causing danger-ous

cerebral edema. Diuretics also may be prescribed to treat the sodium gain.

There is no consensus

about the exact rate at which serum sodium levels should be reduced. As a

general rule, the serum sodium level is reduced at a rate no faster than 0.5 to

1 mEq/L to allow sufficient time for readjustment through diffusion across

fluid compartments. Desmopressin acetate (DDAVP) may be prescribed to treat

diabetes insipidus if it is the cause of hypernatremia.

Nursing Management

As in hyponatremia, fluid losses and gains are carefully monitored in

patients at risk for hypernatremia. The nurse should assess for abnormal losses

of water or low water intake and for large gains of sodium, as might occur with

ingestion of over-the-counter medications with a high sodium content (such as

Alka-Seltzer). Also, it is important to obtain a medication history because

some prescription medications have a high sodium content. In addi-tion, the

nurse notes the patient’s thirst or elevated body tem-perature and evaluates it

in relation to other clinical signs. The nurse monitors for changes in

behavior, such as restlessness, dis-orientation, and lethargy.

PREVENTING HYPERNATREMIA

The nurse attempts to

prevent hypernatremia by offering fluids at regular intervals, particularly in

debilitated patients unable to perceive or respond to thirst. If fluid intake

remains inadequate, the nurse consults with the physician to plan an alternate

route for intake, either by enteral feedings or by the parenteral route. If

enteral feedings are used, sufficient water should be administered to keep the

serum sodium and BUN within normal limits. As a rule, the higher the osmolality

of the enteral feeding, the greater the need for water supplementation.

For patients with

diabetes insipidus, adequate water intake must be ensured. If the patient is

alert and has an intact thirst mechanism, merely providing access to water may

be sufficient. If the patient has a decreased level of consciousness or other

dis-ability interfering with adequate fluid intake, parenteral fluid

re-placement may be prescribed. This therapy can be anticipated in patients

with neurologic disorders, particularly in the early post-operative period.

CORRECTING HYPERNATREMIA

When parenteral fluids are necessary for managing hyperna-tremia, the

nurse monitors the patient’s response to the fluids by reviewing serial serum

sodium levels and by observing for changes in neurologic signs. With a gradual

decrease in the serum sodium level, the neurologic signs should improve. As

stated in the dis-cussion on management, too-rapid reduction in the serum

sodium level renders the plasma temporarily hypo-osmotic to the fluid in the

brain tissue, causing movement of fluid into brain cells and dangerous cerebral

edema (Adrogue & Madias, 2000a).

Related Topics