Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Fluid and Electrolytes: Balance and Distribution

Nursing Management of the Patient Receiving IV Therapy

Nursing

Management of the Patient Receiving IV Therapy

Venipuncture, or the ability to gain access to the venous system for

administering fluids and medications, is an expected nursing skill in many

settings. This responsibility includes selecting the appropriate venipuncture

site and type of cannula and being pro-ficient in the technique of vein entry.

PREPARING TO ADMINISTER IV THERAPY

Before performing venipuncture, the nurse carries out hand hy-giene,

applies gloves, and informs the patient about the proce-dure. Next the nurse

selects the most appropriate insertion site and type of cannula for a

particular patient. Factors influencing these choices include the type of

solution to be administered, the expected duration of IV therapy, the patientŌĆÖs

general condition, and the availability of veins. The skill of the person

initiating the infusion is also an important consideration.

CHOOSING AN IV SITE

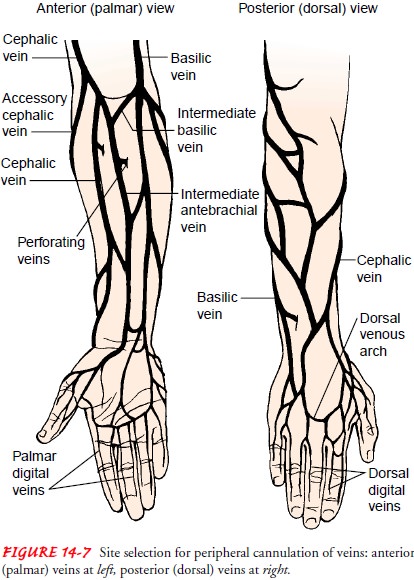

Many sites can be used for IV therapy, but ease of access and po-tential

hazards vary. Veins of the extremities are designated as pe-ripheral locations

and are ordinarily the only sites used by nurses. Because they are relatively

safe and easy to enter, arm veins are most commonly used (Fig. 14-7). The

metacarpal, cephalic, basilic, and median veins as well as their branches are

recommended sites be-cause of their size and ease of access. More distal sites

should be used first, with more proximal sites used subsequently. Leg veins

should rarely, if ever, be used because of the high risk of thromboembolism.

Additional sites to avoid include veins distal to a previous IV infil-tration

or phlebitic area, sclerosed or thrombosed veins, an arm with an arteriovenous

shunt or fistula, or an arm affected by edema, in-fection, blood clot, or skin

breakdown. The arm on the side of a mastectomy is avoided because of impaired

lymphatic flow.

Central veins commonly used by physicians include the sub-clavian and internal jugular veins. It is possible to gain access to (or cannulate) these larger vessels even when peripheral sites have collapsed, and they allow for the administration of hyperosmolar solutions. Hazards are much greater, however, and may include inadvertent entry into an artery or the pleural space.

Ideally, both arms and

hands are carefully inspected before choosing a specific venipuncture site that

does not interfere with mobility. For this reason, the antecubital fossa is

avoided, except as a last resort. The most distal site of the arm or hand is

gener-ally used first so that subsequent IV access sites can be moved

pro-gressively upward. The following are factors to consider when selecting a

site for venipuncture:

┬Ę Condition of the vein

┬Ę Type of fluid or

medication to be infused

┬Ę Duration of therapy

┬Ę PatientŌĆÖs age and size

┬Ę Whether the patient is

right- or left-handed

┬Ę PatientŌĆÖs medical

history and current health status

┬Ę Skill of the person

performing the venipuncture

After applying a

tourniquet, the nurse palpates and inspects the vein. The vein should feel

firm, elastic, engorged, and round, not hard, flat, or bumpy. Because arteries

lie close to veins in the antecubital fossa, the vessel should be palpated for

arterial pulsa-tion (even with a tourniquet on), and cannulation of pulsating vessels

should be avoided. General guidelines for selecting a can-nula include:

┬Ę Length: 3Ōüä4 to 1.25 inches long

┬Ę Diameter: narrow

diameter of the cannula to occupy mini-mal space within the vein

┬Ę Gauge: 20 to 22 gauge

for most IV fluids; a larger gauge for caustic or viscous solutions; 14 to 18

gauge for blood ad-ministration and for trauma patients and those undergoing

surgery

Hand veins are easiest

to cannulate. Cannula tips should not rest in a flexion area (eg, the

antecubital fossa) as this could in-hibit the IV flow.

SELECTING VENIPUNCTURE DEVICES

Equipment used to gain

access to the vasculature includes can-nulas, needleless IV delivery systems,

and peripherally inserted central catheter or midline catheter access lines.

Cannulas.

Most peripheral access devices are

cannulas. Theyhave an obturator inside a tube that is later removed. ŌĆ£CatheterŌĆØ

and ŌĆ£cannulaŌĆØ are terms that are used interchangeably. The main types of

cannula devices available are those referred to as winged infusion sets

(butterfly) with a steel needle or as an over-the-needle catheter with wings,

indwelling plastic cannu-las inserted over a steel needle, and indwelling

plastic cannulas inserted through a steel needle. Scalp vein or butterfly

needles are short steel needles with plastic wing handles. These are easy to

insert, but because they are small and nonpliable, infiltration occurs easily.

The use of these needles should be limited to ob-taining blood specimens or

administering bolus injections or in-fusions lasting only a few hours, as they

increase the risk for vein injury and infiltration. Insertion of an

over-the-needle catheter requires the additional step of advancing the catheter

into the vein after venipuncture. Because these devices are less likely to

cause infiltration, they are frequently preferred over winged in-fusion sets.

Plastic cannulas

inserted through a hollow needle are usually called intracatheters. They are

available in long lengths and are well suited for placement in central

locations. Because insertion requires threading the cannula through the vein

for a relatively long distance, these can be difficult to insert. The most

com-monly used infusion device is the over-the-needle catheter. A hol-low metal

stylet is preinserted into the catheter and extends through the distal tip of

the catheter to allow puncture of the ves-sel, in an effort to guide the

catheter as the venipuncture is per-formed. The vein is punctured and a

flashback of blood appears in the closed chamber behind the catheter hub. The

catheter is threaded through the stylet into the vein and the stylet is then

re-moved. There are many safety over-the-needle catheter designs available with

retracting stylets to protect health care workers from needlestick injuries.

Many types of cannulas are available for IV therapy. Some of the

variations in these cannulas include the thickness of the cannula wall (affects

rate of flow), the sharpness of the insertion needles (determines needle

insertion technique), the softening properties of the cannula (influences the

length of time the can-nula can remain in place), safety features (minimizes

risk of needlestick injuries and blood-borne exposure), and the number of

lumens (determines the number of solutions that can be infused simultaneously).

Cannula systems that help prevent needlesticks and transmission of blood-borne

diseases are discussed below. Most standard peripheral catheters are composed

of some form of plastic. Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene)ŌĆōcoated catheters have

less thrombogenic properties and are less inflammatory than polyurethane or

PVC. Catheter size for steel needles can range from 3Ōüä8 to 1.5 inches in length and 27 to 13 gauge. Plastic catheters range in

length from 5Ōüä8 to 2 inches or as long as 12 inches. The

size of the catheter ranges from 27 to 12 gauge.

To select the ideal product for use, consideration should be given to

which product provides the greatest patient satisfaction and offers quality,

cost-effective infusion care. All devices should be radiopaque to determine

catheter location by x-ray, if indicated. All catheters are thrombogenic and

differ only in their degree of thrombus occurrence. Biocompatibility, another

characteristic of a catheter, ensures that inflammation and irritation do not

occur. Silicone catheters are the most bioinert catheter available today.

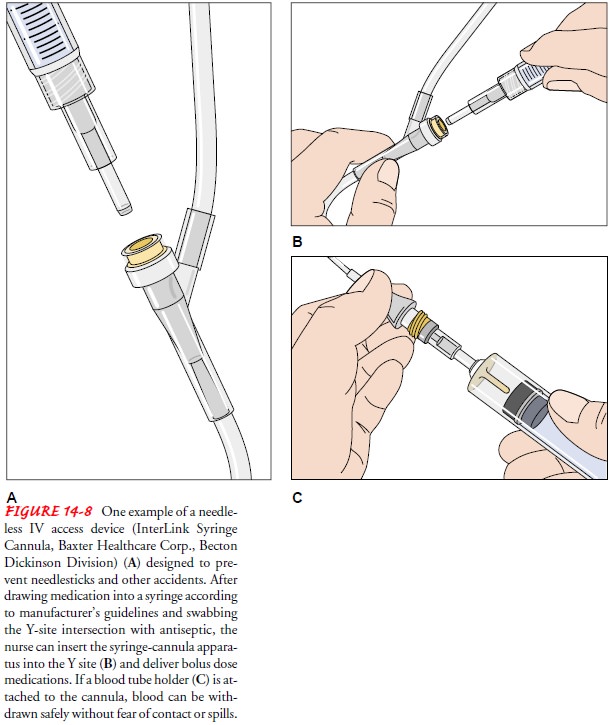

Needleless IV Delivery Systems.

In an effort to decrease needle-stick injuries and exposure to HIV,

hepatitis, and other blood-borne pathogens, agencies have implemented

needleless IV delivery systems. These systems have built-in protection against

needle-stick injuries and provide a safe means of using and disposing of an IV

administration set (which consists of tubing, an area for in-serting the tubing

into the container of IV fluid, and an adapter for connecting the tubing to the

needle). Numerous companies produce needleless components. IV line connectors

allow the si-multaneous infusion of IV medications and other intermittent

medications (known as a piggyback delivery) without the use of needles (Fig.

14-8). Technology is advancing and moving away from use of the traditional

stylet. An example is a self-sheathing stylet that is recessed into a rigid

chamber at the hub of the catheter when its insertion is complete. Other

designs have placed the stylet at the end of a flexible wire to avoid

needlesticks.

Many examples of these devices are on the market. Each insti-tution must

evaluate products to determine its own needs based on OSHA guidelines and the

institutionŌĆÖs policies and procedures.

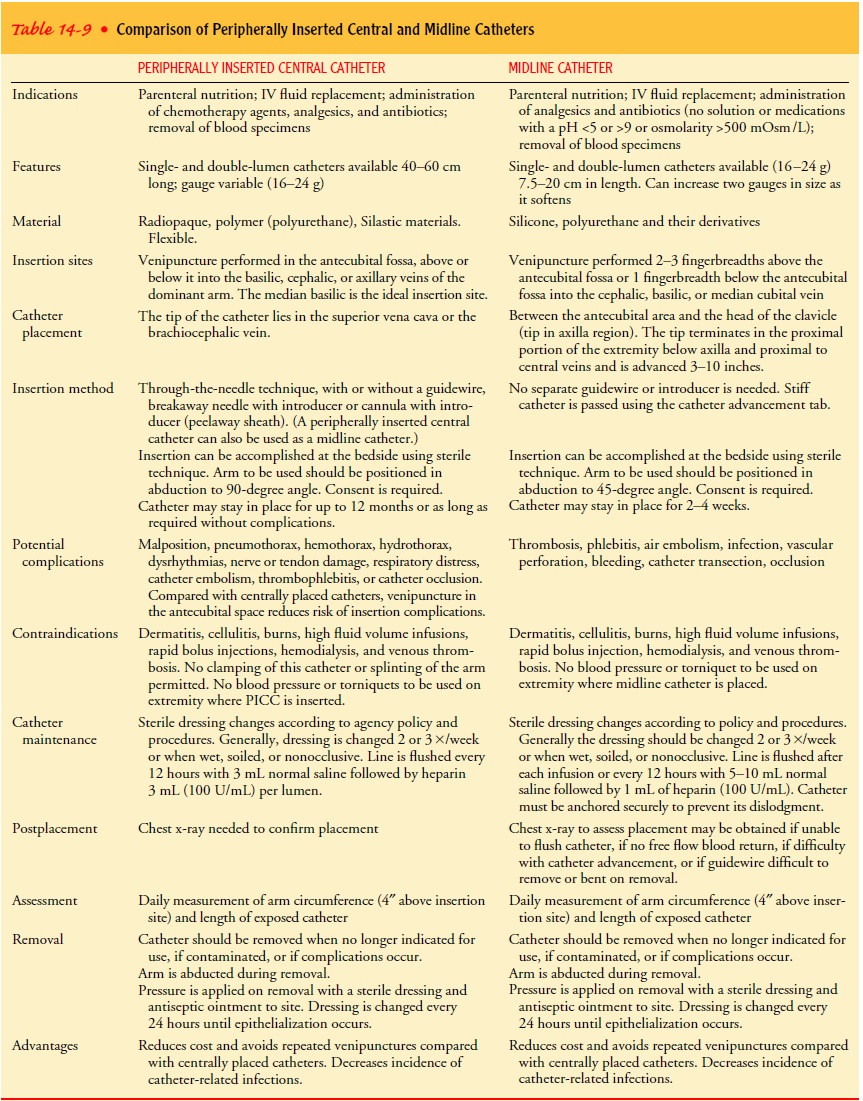

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter or Midline Catheter Access Lines.

Patients who need moderate- to long-termparenteral therapy often receive a peripherally inserted central catheter or a midline catheter. These catheters are also used for

patients with limited peripheral access (eg, obese or emaciated patients,

IV/injection drug users) who require IV antibiotics, blood, and parenteral

nutrition. For these devices to be used, the median cephalic, basilic, and

cephalic veins must be pliable (not sclerosed or hardened) and not subject to

repeated puncture. If these veins are damaged, then central venous access via

the sub-clavian or internal jugular vein, or surgical placement of an

im-planted port or a vascular access device, must be considered as an

alternative. Table 14-9 compares peripherally inserted central and midline

catheter lines.

The principles for

inserting these lines are much the same as those for inserting peripheral

catheters; however, their insertion should be undertaken only by those who are

experienced and spe-cially skilled in inserting IV lines.

The physician prescribes

the line and the solution to be in-fused. Insertion of either line requires

sterile technique. The size of the catheter lumen chosen is based on the type

of solution, the size of the patient, and the vein to be used. The patientŌĆÖs

consent is obtained before use of these catheters. Use of the dominant arm is

recommended as the site for inserting the can-nula into the superior vena cava

to ensure adequate arm move-ment, which encourages blood flow and reduces the

risk of dependent edema.

TEACHING THE PATIENT

Except in emergency situations, a patient should be prepared in advance

for an IV infusion. The venipuncture, the expected length of infusion, and

activity restrictions are explained. Then the pa-tient should have an

opportunity to ask questions and voice con-cerns. For example, some patients

believe they will die if small bubbles in the tubing enter their veins. After

acknowledging this fear, the nurse can explain that usually only relatively

large vol-umes of air administered rapidly are dangerous.

PREPARING THE IV SITE

Before preparing the

skin, the nurse should ask the patient if he or she is allergic to latex or

iodine, products commonly used in preparing for IV therapy. Excessive hair at

the selected site may be removed by clipping to increase the visibility of the

veins and to facilitate insertion of the cannula and adherence of dressings to

the IV insertion site. Because infection can be a major com-plication of IV

therapy, the IV device, the fluid, the container, and the tubing must be

sterile. The insertion site is scrubbed with a sterile pad soaked in 10%

povidoneŌĆōiodine (Betadine) or chlorhexidine gluconate solution for 2 to 3

minutes, working from the center of the area to the periphery and allowing the

area to air day. The site should not be wiped with 70% alcohol be-cause the

alcohol negates the effect of the disinfecting solution. (Alcohol pledgets are

used for 30 seconds instead, only if the pa-tient is allergic to iodine.) The

nurse must perform hand hygiene and put on gloves. Nonsterile disposable gloves

must be worn during the venipuncture procedure because of the likelihood of

coming into contact with the patientŌĆÖs blood.

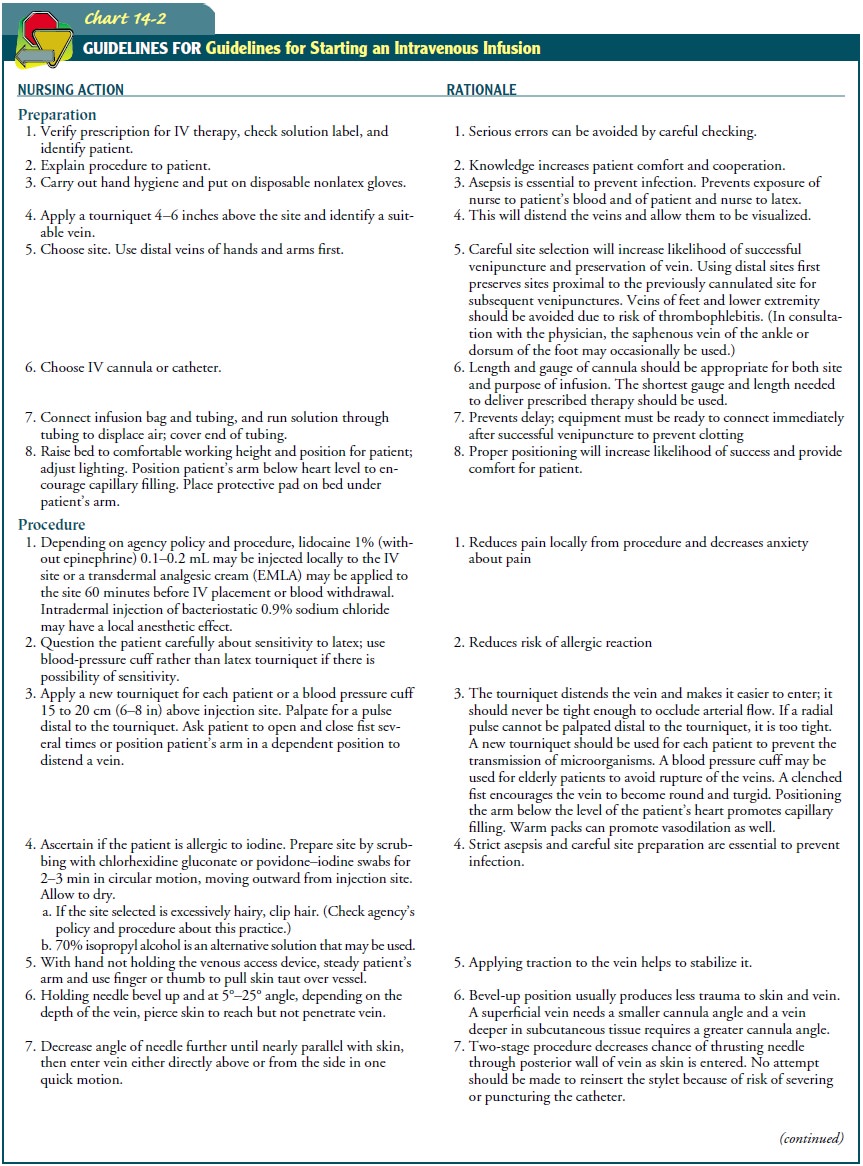

PERFORMING VENIPUNCTURE

Guidelines and a suggested sequence for venipuncture are pre-sented in

Chart 14-2. For veins that are very small or particularly fragile,

modifications in the technique may be necessary. Alter-native methods can be

found in journal articles or in specialized textbooks of IV therapy.

Institutional policies and procedures determine whether all nurses must be certified

to perform venipuncture.

A nurse certified in IV therapy or an IV team can be consulted to assist with

initiating IV therapy.

MAINTAINING THERAPY

Maintaining an existing IV infusion is a nursing responsibility that

demands knowledge of the solutions being administered and the principles of

flow. In addition, patients must be assessed care-fully for both local and

systemic complications.

FACTORS AFFECTING FLOW

The flow of an IV

infusion is governed by the same principles that govern fluid movement in

general.

ŌĆó

Flow is directly proportional to the height of the

liquid col-umn. Raising the height of the infusion container may im-prove a

sluggish flow.

ŌĆó

Flow is directly proportional to the diameter of

the tubing. The clamp on IV tubing regulates the flow by changing the tubing

diameter. In addition, the flow is faster through large-gauge rather than

small-gauge cannulas.

ŌĆó

Flow is inversely proportional to the length of the

tubing. Adding extension tubing to an IV line will decrease the flow.

ŌĆó

Flow is inversely proportional to the viscosity of

a fluid. Vis-cous IV solutions, such as blood, require a larger cannula than do

water or saline solutions.

MONITORING FLOW

Because so many factors influence gravity flow, a solution does not

necessarily continue to run at the speed originally set. There-fore, the nurse

monitors IV infusions frequently to make sure that the fluid is flowing at the

intended rate. The IV container should be marked with tape to indicate at a

glance whether the correct amount has infused. The flow rate is calculated when

the solu-tion is originally started, then monitored at least hourly. To

cal-culate the flow rate, the nurse determines the number of drops delivered

per milliliter; this varies with equipment and is usually printed on the administration

set packaging. A formula that can be used to calculate the drop rate is:

gtt/mL of infusion

set/60 (min in hr) ├Ś total hourly vol = gtt/min

Flushing of a vascular device is performed to ensure patency and prevent

the mixing of incompatible medications or solutions. This procedure should be

carried out at established intervals, ac-cording to hospital policy and

procedure, especially for intermit-tently used catheters. Most manufacturers

and researchers (LeDuc, 1997) suggest the use of saline for flushing. The

volume of the flush solution should be equal to at least twice the volume

capacity of the catheter. The catheter should be clamped before the syringe is

completely empty and withdrawn to prevent reflux of blood into the lumen, which

could cause catheter clotting.

A variety of electronic infusion devices are available to assist in IV

fluid delivery. These devices allow more accurate administration of fluids and

medications than is possible with routine gravity-flow setups. A pump is a

positive-pressure device that uses pressure to infuse fluid at a pressure of 10

psi. Newer models use a pressure of 5 psi. The pressure exerted by the pump

overrides vascular resis-tance (increased tubing length, low height of the IV

container).

Volumetric pumps calculate the volume delivered by measur-ing the volume in a reservoir that is part of the set and calibrated in mL/h. A controller is an infusion assist device that relies on gravity for infusion; the volume is calibrated in drops/min.

A controller uses a drop sensor to monitor the flow. Factors essential for the safe

use of pumps include alarms to signify the presence of air in the IV line and

occlusion. The standard for the accurate delivery of fluid or medication via an

electronic IV infusion pump is plus or minus 5%. The manufacturerŌĆÖs directions

must be read care-fully before using any infusion pump or controller, because

there are many variations in available models. Use of these devices does not

eliminate the need for the nurse to monitor the infusion and the patient

frequently.

DISCONTINUING AN INFUSION

The removal of an IV

catheter is associated with two possible dan-gers: bleeding and catheter

embolism. To prevent excessive bleed-ing, a dry, sterile pressure dressing

should be held over the site as the catheter is removed. Firm pressure is

applied until hemostasis occurs.

If a plastic IV catheter is severed, the loose fragment can travel to

the right ventricle and block blood flow. To detect this complication when the

catheter is removed, the nurse compares the expected length of the catheter

with its actual length. Plastic cathe-ters should be withdrawn carefully and

their length measured to make certain that no fragment has broken off.

Great care must be exercised when using scissors around the dressing

site. If the catheter clearly has been severed, the nurse can attempt to

occlude the vein above the site by applying a tourni-quet to prevent the

catheter from entering the central circulation (until surgical removal is

possible). As always, however, it is better to prevent a potentially fatal

problem than to deal with it after it has occurred. Fortunately, catheter

embolism can be prevented easily by following simple rules:

ŌĆó

Avoid using scissors near the catheter.

ŌĆó

Avoid withdrawing the catheter through the

insertion needle.

ŌĆó

Follow the manufacturerŌĆÖs guidelines carefully (eg,

cover the needle point with the bevel shield to prevent severance of the

catheter).

MANAGING SYSTEMIC COMPLICATIONS

IV therapy predisposes

the patient to numerous hazards, includ-ing both local and systemic

complications. Systemic complica-tions occur less frequently but are usually

more serious than local complications. They include circulatory overload, air

embolism, febrile reaction, and infection.

Fluid Overload.

Overloading

the circulatory system with excessiveIV fluids causes increased blood pressure

and central venous pres-sure. Signs and symptoms of fluid overload include

moist crack-les on auscultation of the lungs, edema, weight gain, dyspnea, and

respirations that are shallow and have an increased rate. Possible causes

include rapid infusion of an IV solution or hepatic, cardiac, or renal disease.

The risk for fluid overload and subsequent pul-monary edema is especially

increased in elderly patients with car-diac disease; this is referred to as

circulatory overload.

The treatment for

circulatory overload is decreasing the IV rate, monitoring vital signs

frequently, assessing breath sounds, and placing the patient in a high FowlerŌĆÖs

position. The physician is contacted immediately. This complication can be

avoided by using an infusion pump for infusions and by carefully monitoring all

infusions. Complications of circulatory overload include heart failure and

pulmonary edema.

Air Embolism.

The

risk of air embolism is rare but ever-present.It is most often associated with

cannulation of central veins. Man-ifestations of air embolism include dyspnea

and cyanosis; hypo-tension; weak, rapid pulse; loss of consciousness; and

chest, shoulder, and low back pain. Treatment calls for immediately clamping

the cannula, placing the patient on the left side in the Trendelenburg

position, assessing vital signs and breath sounds, and administering oxygen.

Air embolism can be prevented by using a Luer-Lok adapter on all lines, filling

all tubing completely with solution, and using an air detection alarm on an IV

pump. Complications of air embolism include shock and death. The amount of air

necessary to induce death in humans is not known; however, the rate of entry is

probably as important as the actual volume of air.

Septicemia and Other Infection.

Pyrogenic substances in eitherthe infusion solution or the IV

administration set can induce a febrile reaction and septicemia. Signs and

symptoms include an abrupt temperature elevation shortly after the infusion is

started, backache, headache, increased pulse and respiratory rate, nausea and

vomiting, diarrhea, chills and shaking, and general malaise. In severe

septicemia, vascular collapse and septic shock may occur. Causes of septicemia

include contamination of the IV product or a break in aseptic technique,

especially in immunocompromised patients. Treatment is symptomatic and includes

culturing of the IV cannula, tubing, or solution if suspect and establishing a

new IV site for medication or fluid administration.

Related Topics