Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Fluid and Electrolytes: Balance and Distribution

Potassium Deficit (Hypokalemia)

POTASSIUM

DEFICIT (HYPOKALEMIA)

Hypokalemia

(below-normal serum potassium concentration) usually indicates an actual

deficit in total potassium stores. Hypo-kalemia may occur in patients with

normal potassium stores; however, when alkalosis is present, a temporary shift

of serum potassium into the cells occurs.

As stated earlier,

hypokalemia is a common imbalance (Gennari, 1998). GI loss of potassium is

probably the most common cause of potassium depletion. Vomiting and gastric

suction fre-quently lead to hypokalemia, partly because potassium is actu-ally

lost when gastric fluid is lost, but more so because potassium is lost through

the kidneys in association with metabolic alka-losis. Because relatively large

amounts of potassium are con-tained in intestinal fluids, potassium deficit

occurs frequently with diarrhea. Intestinal fluid may contain as much potassium

as 30 mEq/L. Potassium deficit also occurs from prolonged intes-tinal

suctioning, recent ileostomy, and villous adenoma (a tumor of the intestinal

tract characterized by excretion of potassium-rich mucus).

Alterations in acid–base balance have a significant effect on potassium

distribution. The mechanism involves shifts of hydro-gen and potassium ions

between the cells and the ECF. Hypo-kalemia can cause alkalosis, and in turn

alkalosis can cause hypokalemia. For example, hydrogen ions move out of the

cells in alkalotic states to help correct the high pH, and potassium ions move

in to maintain an electrically neutral state. (This is dis-cussed further in

the section on acid–base balance.)

Hyperaldosteronism increases renal potassium wasting and can lead to

severe potassium depletion. Primary hyperaldosteronism is seen in patients with

adrenal adenomas. Secondary hyperaldo-steronism occurs in patients with

cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, heart failure, and malignant hypertension

(Wilcox, 1999).Potassium-losing diuretics, such as the thiazides (eg,

chlorothi-azide [Diuril] and polythiazide [Renese]), can induce hypokalemia,

particularly when administered in large doses to patients with inadequate

potassium intake. Other medications that can lead to hypokalemia include

corticosteroids, sodium penicillin, carbeni-cillin, and amphotericin B (Cohn et

al., 2000; Gennari, 1998).

Because insulin promotes

the entry of potassium into skeletal muscle and hepatic cells, patients with

persistent insulin hyper-secretion may experience hypokalemia, which is often

the case in patients receiving high-carbohydrate parenteral fluids (as in

par-enteral nutrition).

Patients who are unable

or unwilling to eat a normal diet for a prolonged period are at risk for

hypokalemia. This may occur in debilitated elderly people, alcoholics, and

patients with anorexia nervosa. In addition to poor intake, people with bulimia

fre-quently suffer increased potassium loss through self-induced vom-iting and

laxative and diuretic abuse.

Magnesium depletion

causes renal potassium loss and must be corrected first; otherwise, urine loss

of potassium will continue. Penicillins may produce renal potassium loss by

acting as poorly reabsorbable anions and thus increasing distal sodium delivery

and sodium-potassium loss.

Clinical Manifestations

Potassium deficiency can result in widespread derangements in

phys-iologic function. Severe hypokalemia can cause death through car-diac or

respiratory arrest. Clinical signs rarely develop before the serum potassium

level has fallen below 3 mEq/L (3 mmol/L) un-less the rate of fall has been

rapid. Manifestations of hypokalemia include fatigue, anorexia, nausea,

vomiting, muscle weakness, leg cramps, decreased bowel motility, paresthesias

(numbness and tingling), dysrhythmias, and increased sensitivity to digitalis

(Gennari, 1998). If prolonged, hypokalemia can lead to an inability of the

kidneys to concentrate urine, causing dilute urine (resulting in poly-uria,

nocturia) and excessive thirst. Potassium depletion depresses the release of

insulin and results in glucose intolerance.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

In hypokalemia, the

serum potassium concentration is less than the lower limit of normal.

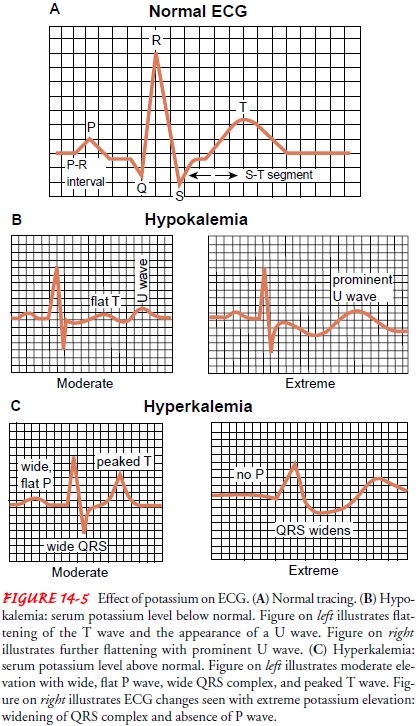

Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes can include flat T waves and/or inverted T

waves, suggesting ischemia, and depressed ST segments (Fig. 14-5). An elevated

U wave is specific to hypokalemia. Hypokalemia increases sensi-tivity to digitalis,

predisposing the patient to digitalis toxicity at lower digitalis levels.

Metabolic alkalosis is commonly associated with hypokalemia. This is discussed

further in the section on acid–base disturbances.

The source of the potassium loss is usually evident from a care-ful

history. When this is not the case, however, and the etiology of the loss is

unclear, a 24-hour urinary potassium excretion test can be performed to

distinguish between renal and extrarenal loss. Urinary potassium excretion

exceeding 20 mEq/24 h with hypo-kalemia suggests that renal potassium loss is

the cause.

Medical Management

If hypokalemia cannot be prevented by conventional measures such as increased intake in the daily diet, it is treated with oral or IV replacement therapy (Gennari, 1998). Potassium loss must be corrected daily; administration of 40 to 80 mEq/day of potassium is adequate in the adult if there are no abnormal losses of potassium.

For patients at risk for hypokalemia, a diet containing sufficient

potassium should be provided. Dietary intake of potassium in the average adult

is 50 to 100 mEq/day. Foods high in potassium in-clude fruits (especially

raisins, bananas, apricots, and oranges), vegetables, legumes, whole grains,

milk, and meat.

When dietary intake is

inadequate for any reason, the physi-cian may prescribe oral or IV potassium

supplements (Gennari, 1998). Many salt substitutes contain 50 to 60 mEq of

potassium per teaspoon and may be sufficient to prevent hypokalemia.When oral

administration of potassium is not feasible, the IV route is indicated. The IV

route is mandatory for patients with severe hypokalemia (eg, a serum level of 2

mEq/L). Although potassium chloride is usually used to correct

potassium deficits, the physician may prescribe potassium acetate or potassium

phosphate.

Nursing Management

Because hypokalemia can be life-threatening, the nurse needs to monitor

for its early presence in patients at risk. Fatigue, anorexia, muscle weakness,

decreased bowel motility, paresthesias, and dys-rhythmias are signals that

warrant assessing the serum potassium concentration. When available, the ECG

may provide useful in-formation. For example, patients receiving digitalis who

are at risk for potassium deficiency should be monitored closely for signs of

digitalis toxicity, because hypokalemia potentiates the action of digitalis.

Physicians usually prefer to keep the serum potassium level above 3.5 mEq/L

(3.5 mmol/L) in patients receiving digi-talis medications such as digoxin.

PREVENTING HYPOKALEMIA

Measures are taken to prevent hypokalemia when possible (Gen-nari,

1998). Prevention may involve encouraging the patient at risk to eat foods rich

in potassium (when the diet allows). Sources of potassium include fruit and

fruit juices (bananas, melon, citrus fruit), fresh and frozen vegetables, fresh

meats, and processed foods. When hypokalemia is due to abuse of laxatives or

diuretics, patient education may help alleviate the problem. Part of the health

his-tory and assessment should be directed at identifying problems amenable to

prevention through education. Careful monitoring of fluid intake and output is

necessary because 40 mEq of potassium is lost for every liter of urine output.

The ECG is monitored for changes, and arterial blood gas values are checked for

elevated bicarbonate and pH levels.

CORRECTING HYPOKALEMIA

Great care should be exercised when administering potassium,

particularly in older adults, who have lower lean body mass and total body

potassium levels and therefore lower potassium re-quirements. Additionally,

with the physiologic loss of renal func-tion with advancing years, potassium

may be retained more readily in older than in younger people.

ADMINISTERING IV POTASSIUM

Potassium should be

administered only after adequate urine flow has been established. A decrease in

urine volume to less than 20 mL/h for 2 consecutive hours is an indication to

stop the potassium infusion until the situation is evaluated. Potassium is

primarily excreted by the kidneys; therefore, when oliguria occurs, potassium

administration can cause the serum potassium concen-tration to rise

dangerously.

Each health care

facility has its own standard of care, which should be consulted; however, IV

potassium should not be ad-ministered faster than 20 mEq/h or in concentrations

greater than 30 to 40 mEq/L unless hypokalemia is severe, because this can

cause life-threatening dysrhythmias. When prepared for IV infusions, the fluid

should be agitated well to prevent bolus doses that can result when the potassium

concentrates at the bottom of the IV container.

When potassium is administered through a peripheral vein, the rate of

administration must be decreased to avoid irritating the vein and causing a

burning sensation during administration. In general, concentrations greater

than 60 mEq/L are not adminis-tered in peripheral veins because venous pain and

sclerosis may occur. For routine maintenance needs, potassium is suitably

di-luted and administered at a rate no faster than 10 mEq/h. In crit-ical

situations, more concentrated solutions (such as 40 mEq/L) may be administered

through a central line. Even in extreme hypo-kalemia, however, potassium should

be administered no faster than 20 to 40 mEq/h (suitably diluted). In such a

situation, the patient must be monitored by ECG and observed closely for other

signs and symptoms, such as changes in muscle strength.

Related Topics