Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Relations: Love

Love

Attraction

tends to bring people closer together. If they are close enough, their

relationship may be more than friendship and become something we celebrate with

the term love. In fact, love involves

many elements: a feeling, a physiological upheaval, a desire for sexual union,

a set of living and parenting arrangements, a sharing of resources (from bank

accounts to friends), a mutual defense and caretaking pact, a merging of

extended families, and more. So complex is human love that, according to some

authorities, psychologists might have been “wise to have abdicated

responsibility for analysis of this term and left it to poets”. Wise or not,

psychol-ogists have tried to say some things about this strange state of mind

that has puzzled both sages and poets throughout the ages.

Psychologists

distinguish among different kinds of love, and some of the resulting

classification systems are rather complex. One scheme tries to analyze love

relation-ships according to the presence or absence of three main components: intimacy (feel-ings of being close), passion (sexual attraction), and commitment (a decision to stay with

one’s partner) (Sternberg, 1986, 1988). Other psychologists propose that there

are two broad categories of love. One is romantic—or passionate—love, the kind

of love that one “falls into,” that one is “in.” The other is companionate

love, a less turbulent state that emphasizes companionship, mutual trust, and

care (Hatfield, 1988).

ROMANTIC LOVE

Romantic love has been described as essentially

passionate: “a wildly emotional state[in which] tender and sexual feelings,

elation and pain, anxiety and relief, altruism and jealousy coexist in a

confusion of feelings”. Lovers feel that they are in the grip of an emotion

they cannot control, which comes across in the very language they use to

describe their love. They “fall in love,” “are swept off their feet,” and

“can’t stop themselves.” Perhaps surprisingly, men tend to fall in love more

often and more quickly than women do, and women tend to fall out of love more

easily than men do (Hill, Rubin, & Peplau, 1976).

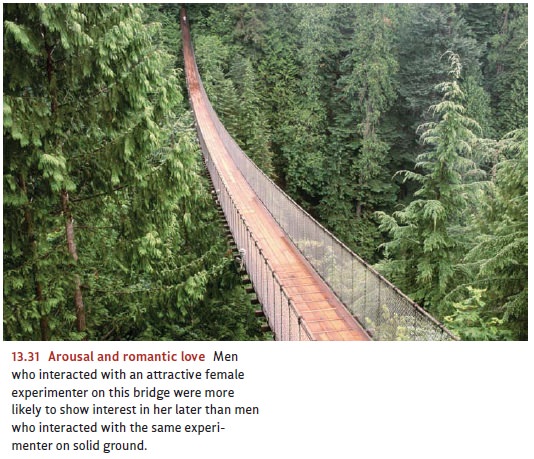

According

to some authors, romantic love involves two distinguishable elements: a state

of physiological arousal, and a set of beliefs and attitudes that leads the

person to interpret this arousal as passion. What leads to the arousal itself ?

One obvious source is erotic excitement, but other forms of stimulation may

have the same effect. Fear, pain, and anxiety can all heighten general arousal

and so can, in fact, lend fuel to romantic passion. One demonstration comes

from a widely cited experiment in which

men

were approached by an attractive young woman who asked them to fill out a

ques-tionnaire (allegedly to help her with a class project); she then gave them

her telephone number so they could call her later if they wanted to know more

about the project. The study was conducted in Capilano Park, just north of

Vancouver, British Columbia. The park is famous for its narrow, wobbly

suspension bridge, precariously suspended over a shallow rapids 230 feet below

(Figure 13.31). Some of the men in the study were approached while they were on

the bridge itself. Others were approached after they had already crossed the

bridge and were back on solid ground.

Did

the men actually call the young woman later—ostensibly to discuss the

experiment, but really to ask her for a date? The likelihood of their making

this call depended on whether they were approached while they were on the

bridge or later, after they had crossed it. If they filled out the

questionnaire while crossing the bridge—at which point they might well have

felt some fear and excitement—the chances were almost one in three that the men

would call. If they met the young woman when they were back on safe ground, the

chances of their doing so were very much lower (Dutton & Aron, 1974; but

see also Kenrick & Cialdini, 1977; Kenrick, Cialdini, & Linder, 1979).

What is going on here? One way to think about it is to call to mind the

Schachter-Singer theory of emotion. Being on the bridge would make almost

anyone feel a little jittery—it would, in other words, cause a state of

arousal. The men who were approached while on the bridge detected this arousal,

but they seem to have misinterpreted their own feelings, attributing their elevated

heart rate and sweaty palms not to fear, but to their interest in the woman.

Then, having misread their own state, they followed through in a sensible way,

telephoning a woman whom they believed had excited them.

This

sequence of events may help us understand why romantic love seems to thrive on

obstacles. Shakespeare tells us that the “course of true love never did run

smooth,” but if it had, the resulting love probably would have been lacking in

ardor. The fervor of a wartime romance or an illicit affair is probably fed in

part by danger and frustra-tion, and many a lover’s passion becomes all the

more intense for being unrequited. All of these cases involve increased

arousal, whether through fear, frustration, or anx-iety. We interpret this arousal

as love, a cognitive appraisal that fits in perfectly with our romantic ideals,

which include both the rapture of love and the agony.

An

interesting demonstration of this phenomenon is the so-called Romeo-and-Juliet effect (named after

Shakespeare’s doomed couple, whose parents violentlyopposed their love; Figure

13.32). This term describes the fact that parental opposition tends to

intensify a couple’s romantic passion rather than to diminish it. In one study,

couples were asked whether their parents interfered with their relationship.

The greater this interference, the more deeply the couples fell in love

(Driscoll, Davis, & Lipetz, 1972). The moral is that if parents want to

break up a romance, their best bet is to ignore it. If the feuding Montagues

and Capulets had simply looked the other way, Romeo and Juliet might well have

become bored with each other by the end of the second act.

COMPANIONATE LOVE

Romantic

love tends to be a short-lived bloom. That wild and tumultuous state, with its

intense emotional ups and downs, with its obsessions, fantasies, and

idealizations, rarely, if ever, lasts forever. Eventually the adventure is

over, and romantic love ebbs. Sometimes it turns into indifference or active

dislike. Other times (and hopefully more often) it transforms into a related

but gentler state of affairs—companionate

love (Figure 13.33). This type of love is sometimes defined as the

“affection we feel for those with whom our lives are deeply intertwined”. In

companionate love, the similarity of outlook, mutual caring, and trust that

develop through day-to-day living become more important than the fantasies and

idealization of romantic love, as the two partners try to live as happily ever

after as it is possible to do in the real world. This is not to say that the

earlier passion does not flare up occa-sionally. But it no longer has the

obsessive quality that it once had, in which the lover is unable to think of

anything but the beloved (Caspi & Herbener, 1990; Hatfield, 1988; Neimeyer,

1984).

CULTURE

AND

LOVE

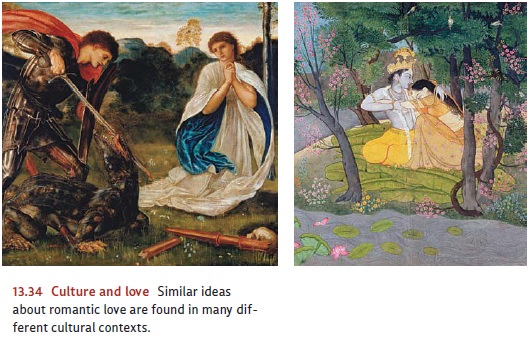

It

will come as no surprise that concep-tions of love are—like the many other

aspects of our interactions with others—a cultural product. Western cultural

notions of what love is and what falling in love feels like have been fashioned

by a histori-cal heritage that goes back to Greek and Roman times (with tales

of lovers hit by Cupid’s arrows), was revived during the Middle Ages (with

knights in armor slay-ing dragons to win a lady’s favor), and was finally

mass-produced by Hollywood (with a final fade-out in which the couple embraces

and lives happily ever after). This complex set of ideas about what love is,

and who is an appropriate potential love object, constitutes the context that

may lead us to interpret physiological arousal as love.

Similar

ideas about romantic love are found in many other cultures (Figure 13.34).

Hindu myths and Chinese love songs, for example, celebrate this form of love,

and, indeed, a review of the anthropological research revealed that romantic

love was pres-ent in 147 of 166 cultures (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992). Even

so, it seems unlikely that any other culture has emphasized romantic love over

companionate love to the extent that Western culture does (e.g., De Rougemont,

1940; V. W. Grant, 1976). This is reflected in many ways, including the fact

that popular American love songs are only half as likely as popular Chinese

love songs to refer to loyalty, commitment, and endur-ing friendship, all

features of companionate love (Rothbaum & Tsang, 1998).

Why

do cultures differ in these ways? One proposal derives, again, from the

contrast between individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Collectivistic

cultures emphasize connection to one’s group, and this makes it unsurprising

that (collectivistic) China would prefer songs emphasizing loyalty—a focus on

the relationship, rather than on each individual’s feelings. To put this point

differently, romantic love often places a high premium on pursuing personal

fulfillment, even, and perhaps especially, when it con-flicts with other

duties. On this basis, members of individualistic cultures are more likely than

those in collectivistic cultures to consider romantic love important for

mar-riage. (Dion & Dion, 1996).

Related Topics