Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Cognition: Person Perception

Person Perception

When

we make causal attributions, we go beyond the information available to our

senses in order to make sense of a particular action—why someone smiled, or did

well on a test, or didn’t help more after an accident. Th13 role of social

cognition— and our tendency to supplement what we perceive—is just as important

when we try to make sense of another person—that is, whenever we ask ourselves,

“What kind of person is she?”

IMPLICIT THEORIES OF PERSONALITY

Imagine

that a friend says her sister Marie is especially outgoing. Or say that you see Marie at several parties, and each time she’s

the center of attention. In either case, you’re likely to draw some inferences

from what you hear about Marie or how you see her behaving—but in the process,

you may lose track of which bits of information are based directly on what

you’ve heard or seen and which bits are merely your interpretation. Thus, if

you hear that Marie is outgoing, you may also remember (falsely) that your

friend said she loves crowds, even though that was never mentioned (N. Cantor

& Mischel, 1979; Dweck, Chiu, & Hong, 1995).

In

this way, social cognition works much like other kinds of cognition. Our

knowl-edge of the world is a blend of our own observations and the inferences

we have made using our schematic knowledge—knowledge

about the world in general. In the social domain, these schemas are called implicit theories of personality

(Bruner & Tagiuri, 1954; D. J. Schneider, 1973), and we use them to make

inferences about what a person is really like and how she is likely to behave

in the future. We all hold these informal the-ories, and they bring together a

cluster of beliefs, linking one trait (such as extraversion) to others (such as

loving crowds) but also linking these traits to specific behaviors—so that we have

expectations for what sort of husband the extravert will be, what sorts of

sports he is likely to enjoy, and more.

These implicit theories are another point on which cultures differ (Church et al., 2006). People in individualistic cultures tend to understand the self as being stable across time and situations and so are more likely to go beyond the information given and make global judgments about others’ personalities. People in collectivistic cul-tures, where the self is understood as changing according to relationships and situa-tions, tend to view personality as malleable. They therefore tend to make more cautious and more limited generalizations about other people’s personalities (Hong, Chiu, & Dweck, 1997).

STEREO TYPES

Implicit

theories of personality—like schemas in any other domain—are enormously

helpful. Thanks to these schemas, we do not have to scrutinize every aspect of

every situation we encounter, because we can fill in any information we are missing

by drawing on our schematic knowledge. Likewise, if our current information

about a person is lim-ited (perhaps because we only met her briefly), we can

still make reasonable assumptions about her based on what we know about people

in general. Though these steps make our social perception quick and efficient

and generally lead us to valid inferences, they do leave us vulnerable to

error, so that our perception (or recollection) of another person some-times

ends up more in line with our preconceptions than with the facts. In many cases

this is a small price to pay for the benefits of using schemas, and for that

matter, the errors pro-duced are often easily corrected. But schemas can also

lead to more serious errors.

The

hazard of schematic thinking is particularly clear in the case of social stereo-types, schemas about the

characteristics of whole groups that lead us to talk aboutGreeks, Jews, or

African Americans (or women, the elderly, or liberals and conservatives) as if

we know all of them and they are all the same (Figure 13.4). These stereotypes

are, on their own, worrisome enough, because they can lead us to make serious

errors of judgment about the different people we meet. Worse, stereotypes can

lead to deeper problems, including (at the extreme) wars, genocides, and

“ethnic cleansings.” These larger calamities, however, are not fueled by

stereotypes alone. They arise from prejudice,

which can be defined as a negative attitude toward another per-son based on his

group membership. Prejudice consists of three factors sometimes referred to as

the ABCs of prejudice: an affective

(emotional) component, which leads us to view the other group as “bad”; a behavioral component, which includes our

ten-dencies to discriminate against other groups; and a cognitive component (the stereo-type itself ). Prejudice can lead

to extreme cruelties and injustices, making the study of intergroup bias in

general, and stereotypes and prejudice in particular, a topic of some urgency.

ORIGINS AND MEASUREMENT OF STEREOTYPES

Whether

stereotypes are negative or positive, they often have deep historical roots and

are transmitted to each new generation both explicitly (“Never trust a . . .”)

and implic-itly (via jokes, caricatures, portrayals in movies, and the like). Thus,

in Western cul-tures, we hear over and over about athletic blacks, academic

Asians, moody women, and lazy Latinos, and, like it or not, these associations

eventually sink in and are likely to affect our behavior—regardless of whether

we believe that the association has any factual basis.

Other

factors also foster the creation and maintenance of stereotypes. Consider, for

example, the fact that most of us have a lot of exposure to people in our own

group, and as a result, we have ample opportunity to see that the group is

diverse and made up of unique individuals. We generally have less exposure to

other groups, and so, with little opportunity for learning, we are likely to

perceive the group as merely a mass of more or less similar people. This so-called

out-group homogeneity effect is

reflected in such statements as “All Asians are alike” or “All Germans are

alike.” The first statement is almost invariably made by a non-Asian; the

second, by a non-German.

Just

a few decades ago, many people did not hesitate to make derogatory comments in

public settings about blacks, or women, or Jews. This made studying stereotypes

relatively straightforward, in that researchers could use explicit measures, which involve some form of self-report, to

assess negative stereotypes about groups of individuals.

The

times have changed, however, and stereotyping has become much less socially

acceptable in most quarters of life. As a result, people are now much less

likely to endorse explicitly racist or sexist statements than they were in the

recent past. Does this mean stereotypes no longer matter? Unfortunately not.

Stereotypes still influence people’s behavior, but the effects are quite

subtle, often happening automatically, outside our awareness (Bargh, Chen,

& Burrows, 1996; but see also Cesario, Plaks, & Higgins, 2006).

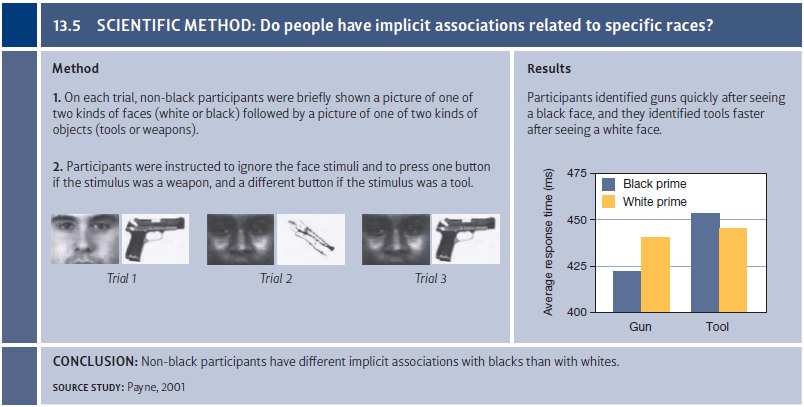

To

assess these less overt stereotypes, researchers have begun to use implicit measures. For example, some

researchers have measured brain responses to stereotype-relevant stimuli (Ito,

Willadsen-Jensen, & Correll, 2007) or response times to stereotype-related

questions (Fazio, 1995). These implicit measures allow us to detect biases that

people might prefer to keep hidden. They also allow us to observe biases that

people don’t even realize they have—biases that, in fact, conflict with the

person’s explicit (conscious) beliefs. Thus, people who explicitly hold

egalitarian views may still have assumptions about various outgroup members,

unconsciously believing, for example, that African Americans are more likely

than whites to be criminals, or that Hispanics are more hot-tempered than

non-Hispanics (Blair & Banaji, 1996; Chen & Bargh, 1997; Kawakami,

Dion, & Dovidio, 1998; Wittenbrink, Judd, & Park, 1997). In fact, this

conflict between conscious beliefs and unconscious assumptions and associations

seems to occur rela-tively often, thanks to the fact that our implicit and

explicit views are shaped by differ-ent influences, and so can sometimes

contradict each other (e.g., Nosek, 2007; Rydell, McConnell, Mackie, &

Strain, 2006).

Another

commonly used means of detecting implicit assumptions and associations is the

Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 2002; Greenwald, McGhee,

& Schwartz, 1998; Grenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003).* In the classic

version of the IAT, people are asked to make two types of judgments: whether a

face they see on the com-puter screen is that of a black person or a white

person, and whether a word they see on the screen is a “good” word (e.g., love, joy, honest, truth) or a “bad”

word (e.g., poison,agony, detest,

terrible). This seems simple enough, but the trick here is that the trials

withfaces (black or white) are intermixed with the trials with words (good or

bad), and par-ticipants must use the same two keys on the computer for both

judgments. Thus, in one condition, participants must use one key to indicate

“black” if a black face is shown and the same key to indicate “good” if a good

word is shown; a different key is used for “white” (for face trials) and “bad”

(for word trials). In another condition, things are arranged differently: Now

participants use one key to indicate “black” and “bad” (for faces and words,

respectively) and the other key to indicate “white” and “good.”

This

experiment assesses how easily the participants can manage each of these links.

Do they have an easier time putting “white” and “good” together (and so using

the same key to indicate both) than putting “white” and “bad” together? It

turns out that the first combination is easier for white research

participants—and for many African American participants as well (Figure 13.5).

This seems to suggest that the participants arrive at the experiment already

primed to associate each race with a certain evaluation

and

respond more slowly when the experiment requires them to break that association

(see, for example, W. A. Cunningham, Preacher, & Banaji, 2001; Greenwald et

al., 2002; Greenwald et al., 1998; B. K. Payne, 2001).

THE EFFECTS OF STEREOTYPES

Whether

implicit or explicit, stereotypes have multiple effects. They influence what we

believe about other people and how we act toward them. Perhaps worst of all,

stereo-types influence how the targets of our stereotypes act—so that,

specifically, the stereotype leads members of the targeted group to behave in a

way that confirms the stereotype. In this way, stereotypes create self-fulfilling prophecies.

In

a classic demonstration, Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) told a group of

elementary-school teachers that some of their students were “bloomers” and

could be expected to show substantial increases in IQ in the year ahead.

Although these “bloomers” were ran-domly chosen, they in fact showed

substantial increases in their test scores over the course of the next year, an

effect apparently produced by the teachers’ expectations. Several fac-tors

probably contributed to this effect, including the greater warmth and

encouragement the teachers offered, the individualized feedback they provided,

and the increased number of opportunities they gave the children they expected

would do well (M. J. Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; for a cautionary note about

the reliability of these effects, see Jussim & Harber, 2005; R. Rosenthal,

1991, 2002; H. H. Spitz, 1999).

How

does this finding apply to stereotypes? Here, too, it turns out that people are

heavily influenced by others’ expectations—even when we are considering

expectations for a group, rather than

expectations for an individual. As we saw, this influence is plainly visible in

the way that stereotype threatinfluences performance on tests

designed to measure intellectual ability. In one study, for example,

experimenters gave intelligence tests to African American students. Before

taking the test, half of the students were led to think briefly about their

race; the other half were not. The result showed—remarkably—that the students

who thought about their race did less well on the test (Steele, 1998). In other

studies, women have been given math tests, and just before the test, half have

been led to think briefly about their gender. This reminder leads the women to

do more poorly on the test (Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999).

What’s

going on in these studies? These reminders about group membership lead the test

takers to think about the stereotypes for their group—that African Americans

are unintelligent, or that women can’t do math—and this makes the test takers

anx-ious. They know that others expect them to do poorly, and they know that if

they do not perform well, they will just confirm the stereotype. These fears

distract the test takers, consume cognitive resources, and undermine their

performance—so that the stereo-type ends up confirming itself (Johns, Inzlicht,

& Schmader, 2008). In addition, the test takers may fear that the

stereotype is to some extent correct, and this fear may lead the test takers to

lower their expectations and not try as hard. This, too, would under-mine

performance, which in turn would confirm the ugly stereotype.

Related Topics