Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Influence: Conformity

Conformity

People

often do what they see others do. Sometimes this is a good thing, such as when

people cross at the crosswalk, throw their trash in garbage cans, or drive on

the side of the road they are supposed to. However, people’s propensity to do

as others do can also be a bad thing, as when people litter or even steal when

they see that others are failing to behave appropriately (Keizer, Lindenberg,

& Steg, 2008). Confirmity occurs

when-ever people change their behavior because of social pressure (either

explicit or implicit).

One

early demonstration of conformity comes from a classic study by Sherif (1937).

In this study, participants seated in a dark room saw a point of light appear,

move, and then disappear. This happened a number of times, and the

participants’ task was sim-ply to judge how far the light had moved on each

trial. In reality, however, the light never moved, and the appearance of

movement was the result of a perceptual illusion known as the autokinetic

effect.

When

participants made their judgments alone, their responses differed

substan-tially from one person to the next, ranging from an inch to more than a

foot. Participants’ responses also varied considerably from trial to trial.

When participants viewed the light with one or two other people, however, their

responses quickly began to converge with those of the other members of their

group. Different groups converged upon different answers, but in each case the

participants rarely strayed from the norm that had developed in their

particular group.

Most

telling, perhaps, was what Sherif found when he placed a confederate into the

situation, someone who appeared to be a participant, but who in reality was an

accom-plice of the experimenters. When the confederate made responses that were

much lower than those typically made by solitary participants, the other (real)

participants quickly followed suit, and a group norm emerged that was much

lower than normal. Similarly, when the confederate made responses that were

much higher than typical, the others again followed this lead, and the

resulting group norm was much higher than usual.

Sherif ’s findings are provocative because they suggest that others can influence even our basic perceptions of the world. Note, though, that Sherif had concocted a highly ambiguous situation in which participants were literally groping in the dark for an answer. Do people conform even when the correct answer is obvious?

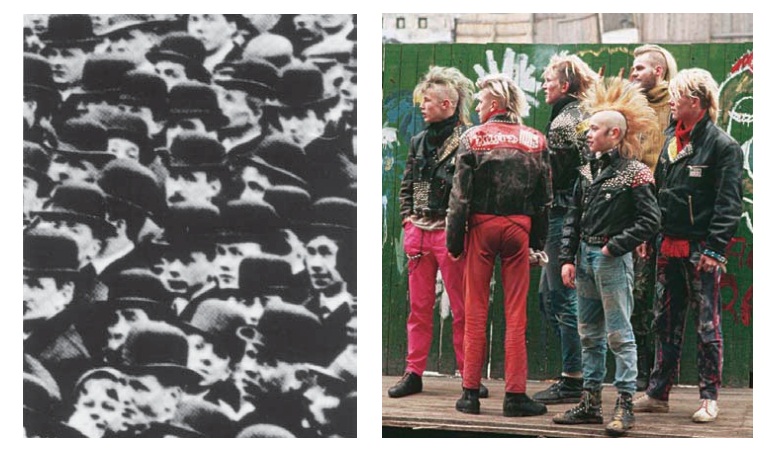

Solomon

Asch developed a procedure in which there could be no doubt as to the cor-rect

response (Asch, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1956). In his experiments, Asch brought

groups of people into the laboratory and showed them pairs of cards, placed a

few feet away (Figure 13.12). On one card was a black line, say, 8 inches long.

On the other card were three lines of varying lengths, say, 6, 8, and 7 inches.

The participants were asked sim-ply to pick which of the three lines on the one

card was equal in length to the single line on the other card.

The

three lines were clearly different, and one of them exactly matched the

origi-nal line, so the task was absurdly simple. But there was a catch. There

was actually only one real participant. All of the others were confederates,

with their seats arranged so that most of them would call out their judgments

before the real partici-pant had his turn.

In

the first few trials, the confederates each called out the correct response and

the real participant did the same. After the initial trials, however, the

confederates began to unanimously render false judgments on most of the

trials—declaring, for example, that a 6-inch line equaled an 8-inch line, and

so on (Figure 13.13). In this situation, the clear evidence of the

participant’s senses was contradicted by everyone around him, so what should he

do? Asch found that most participants wavered—sometimes offering the correct

response but on many other trials yielding to the obviously mistaken suggestion

offered by the group. Indeed, the chances were less than one in four that the

participant would be fully independent and would stick to his guns on all trials

on which the group disagreed with him (for an analysis that highlights the

striking independence of some participants, see Friend, Rafferty, & Bramel,

1990).

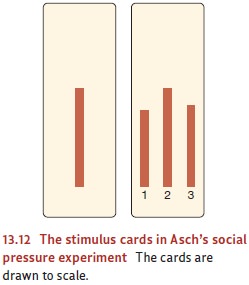

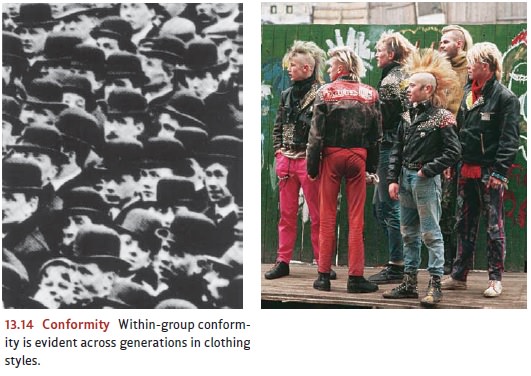

THE CAUSES OF CONFORMITY

Why

do people conform—in Asch’s studies, and in many other settings (Figure 13.14)?

Two influences appear to be crucial (M. Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The

first—known as informational influence—involves

people’s desire to be right (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Researchers have

demonstrated the role of this sort of influence by altering the Asch-type

experiment to make discriminating among the line segments very difficult. In

this setting, we might expect people to be confused about the correct answer,

and therefore more likely to seek out other cues for how they should respond.

Plausibly, they might listen more to what others say—leading to the predic-tion

that with more difficult discriminations, more social conformity will occur.

This prediction is correct (Crutchfield, 1955). Conversely, we can alter the

situation so that participants have less

reason to listen to others (e.g., by convincing participants they are more

competent or knowledgeable than others in some domain). In this case, we would

expect the participants to rely less on the others’ views, and so we would

predict less conformity. This prediction also is correct (Campbell, Tesser,

& Fairey, 1986; Wiesenthal, Endler, Coward, & Edwards, 1976).

This line of reasoning helps to explain why, in general, people seek the opinion of others when they encounter a situation that they do not fully understand. To evaluate the situation, they need more information. If they cannot get it firsthand, they will ask others, and if that is not an option, then they can try to gain information by comparing their own reactions to those of others (Festinger, 1954; Suls & Miller, 1977). This pat-tern of relying on others in the face of uncertainty can also be observed in young children, and even in infants. Infants who confront a scary situation and do not know whether to advance or retreat will glance toward their caretaker’s face. If she smiles, the infant will tend to advance; if she frowns, he will tend to withdraw and return to her. This early phenomenon of socialreferencing may be the prototype for what happens all our lives, a general process ofvalidating our reactions by checking on how others are behaving.

Another

aspect of informational influence is that the decisions of other people can

shape the information we receive, and this, too, can lead to conformity.

Suppose you’re trying to decide what type of car to buy. If two of your

neighbors have purchased Toyotas, you’ll have a chance to observe these cars

closely and learn about their attrib-utes. In this way, your neighbors’

selection will bias the information available and may lead you to follow their

lead when you choose your own car (Denrell, 2008).

A

second reason for going along with the crowd—known as normative influence— revolves around people’s desire to be liked, or

at least not to appear foolish (B. Hodges & Geyer, 2006). Consider the

original Asch study in which a unanimous majority made an obviously incorrect

judgment. In this context, the participant likely saw the world much as it is,

but he had every reason to believe that the others saw it differently. If he

now said what he believed, he could not help but be embarrassed; the others

would probably think that he was a fool and might laugh at him. Under the

circumstances, the participant would prefer to disguise what he really believed

and go along, preferring to be “normal” rather than correct.

Direct evidence for the role of embarrassment as a normative influence comes from a variant of the Asch experiment in which the participant entered the room while the experiment was already in progress. The experimenter told her that since she arrived late, it would be simpler for her to write down her answers rather than to announce them out loud. Under these circumstances, there was little conformity. The lines being judged were of the original unambiguous sort (e.g., 8 inches vs. 6 inches in height), so that there was no informational pressure toward conformity. Since the judgments were made in private (no one else knew what she had written down), there was no (or little) motivational pressure either. As a result, participants showed a great deal of independ-ence (Asch, 1952).

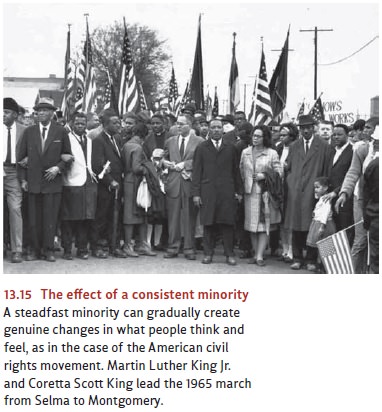

MINORITY INFLUENCE

Asch’s

studies tell us that a unanimous majority exerts a powerful effect that makes

it difficult for any individual to stray from the majority ’s position. What

happens, though, when the individual is no longer alone? In one variation of

his experiment, Asch had one of the confederates act as the participant’s ally;

all of the other con-federates gave wrong answers, while the ally ’s judgments

were correct. Under these conditions, the pressure to conform largely

evaporated, and the participant yielded rarely and was not particularly upset

by the odd judgment offered by (the majority of ) the confederates.

Was

the pressure to conform reduced because the ally shared the participant’s

views? Or was it merely because the consensus was broken, so that the

participant was no longer alone in questioning the majority view? To find out,

Asch conducted a variation of the study in which a confederate again deviated

from the other confederates, but did not do so by giving the correct answer. On

the contrary, she gave an answer even farther from the truth than the group’s.

Thus, on a trial in which the correct answer was 6 1/4 inches and

the majority answer was 6 3/4 inches, the confederate’s answer might

be 8 inches. This response did not sup-port the participant’s perception (or

reflect the truth!), but it helped to liberate him even so. The participant now

yielded much less than when he was confronted by a unanimous majority. What

evidently mattered was the group’s unanimity; once this was broken, the

par-ticipant felt that he could speak up without fear of embarrassment (Asch,

1952). Similar studies have been performed in other laborato-ries with similar

results (V. L. Allen, 1975; V. L. Allen & Levine, 1971; Nemeth &

Chiles, 1988). The power of even a lone dissident sug-gests that totalitarian

systems have good reason to stifle dissent of any kind. The moment one

dissident voice is raised, unanimity is broken, and then others may (and often

do) find the courage to express their own dissent (Figure 13.15).

CULTURE

AND

CONFORMITY

Asch’s

studies of conformity and most others like it were conducted on participants

from an individualistic society, the United States. Many of these participants

did conform but experienced enormous discomfort as a result, plainly suffering

from the contrast between their own perceptions and the perceptions of others.

The pattern is different in collectivistic cultures. Here individuals are less

distressed about conform-ing even when it means being wrong. Over two dozen

Asch-type conformity studies have now been conducted in collectivistic

cultures, and they support such a conclusion (Bond & Smith, 1996).

Members of collectivistic and individualistic societies tend to differ in other ways too. Consider the group pressure that presumably led to conformity in Asch’s experi-ments. On the face of it, one might expect collectivists to be more sensitive to this pres-sure, and so to endorse the group’s judgments more often than do individualists. But it turns out that for collectivists, the likelihood of conformity depends on the nature of the group. Collectivists are more likely to conform with members of a group to which they are tied by traditional bonds—their family (including extended family), class-mates, close friends, and fellow workers. In contrast, they are less affected than are indi-vidualists by people with whom they do not share close interpersonal bonds (Moghaddam, 1998).

Related Topics