Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Relations: Attraction

Attraction

Acts of aggression or acts of helping often involve isolated incidents. Someone cuts you off in traffic, and you angrily honk your horn; a stranger on a street corner asks you for a few coins, and you do (or perhaps don’t) give some. Other forms of social relationship are more enduring—and can color your life for many years. These long-lasting relation-ships include friendship and the exciting, comforting, and sometimes vexing relation that we call love.

What

initially draws people together as friends or lovers? How do we win someone’s

affections? How do close relationships change over the long term?

ATTRACTIVENESS

Common

sense tells us that physical appearance is an important determinant of attrac-tion,

and formal evidence confirms that point. In one study, freshmen were randomly

paired at a dance and later asked how much they liked their partner and whether

he or she was someone they might want to date. After this brief encounter, what

mainly determined each person’s desirability as a future date was his or her

physical attractive-ness (Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottman, 1966).

Similar results were found among clients of a commercial dating service who

selected partners based on files that included a photograph, background

information, and details about interests, hobbies, and personal ideals. When it

came down to the actual choice, the primary determinant was the photograph (S.

K. Green, Buchanan, & Heuer, 1984).

Physically

attractive individuals also benefit from the common tendency to associate

physical attractiveness with a variety of other positive traits, including

intelligence, happiness, and good mental health (e.g., Bessenoff & Sherman,

2000; Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972; Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, &

Longo, 1991; Feingold, 1992; Jackson, Hunter, & Hodge, 1995; Langlois et

al., 2000). This is, in fact, part of a larger pattern sometimes referred to as

the halo effect, a term that refers

to our tendency to assume that people who have one good trait are likely to

have others (and, conversely, that people with one bad trait are likely to be

bad in other regards as well). In some cases, there may be a kernel of truth in

this pattern of beliefs, but unmistakably the “halo” extends farther than it

should (Anderson, Adams, & Plaut, 2008). For example, people seem to make

judgments about how competent someone

is based only on facial appearance, and so, remarkably, judgments about

appearance turn out to be powerful predictors of whom people will vote for in

U.S. congressional elections (Todorov, Mandisodza, Goren, & Hall, 2005).

PROXIMITY

A

second important factor in determining attraction is sheer proximity (Figure

13.28). By now, dozens of studies have shown that if you want to predict who

will make friends with whom, the first thing to ask is who is nearby. Students

who live next to each other in a dormitory or sit next to each other in classes

develop stronger relations than those who live or sit only a bit farther away

(Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008). Similarly, members of a bomber crew

became much friendlier with fellow crew mem-bers who worked right next to them

than with others who worked only a few feet away (Berscheid, 1985).

In

this case, what holds for friendship also holds for mate selection. The

statistics are rather impressive. For example, one classic study considered all

the couples who took out marriage licenses in Columbus, Ohio, during the summer

of 1949. Among these couples, more than half were people who lived within 16

blocks of each other when they went out on their first date (Clarke, 1952).

Much the same holds for the

probability

that an engagement will ultimately lead to marriage; the farther apart the two

live, the greater the chance that the engagement will be broken off (Berscheid

& Walster, 1978).

Why

is proximity so important? Part of the answer simply involves logistics rather

than psychology. You cannot like someone you have never met, and the chances of

meeting that someone are much greater if he is nearby. In addition, even if you

have met someone and begun a relationship, distance can strain it. Indeed, the

prospect of commuting and of communicating only by email and phone calls

corrodes many marriages and ends many high school romances.

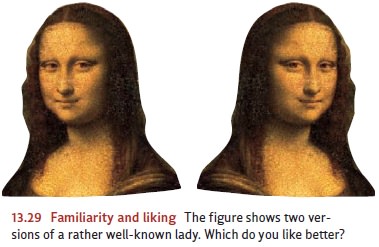

Beyond

these obvious points, though, it also turns out that getting to know some-one

makes him more familiar to you, and

familiarity in turn is itself a source of attrac-tion. Indeed, whether we are

evaluating a word in a foreign language, a melody, or the name of a commercial

product, studies indicate that the more often something is seen or heard, the

better it will be liked (Coates, Butler, & Berry, 2006; Moreland &

Zajonc, 1982; Zajonc, 1968; also see Norton, Frost, & Ariely, 2007).

Familiarity probably plays an important role in determining what we feel about

other people as well. For example, people judge photographs of strangers’ faces

to be more likable the more often they have seen them (Jorgensen & Cervone,

1978). Likewise, which is preferred—a photo of a familiar face, or a

mirror-image of that photo? If familiarity is the critical variable, our

friends should prefer a photograph of our face to one of its mirror image,

since they have seen the first much more often than the second. But we

ourselves should prefer the mirror image, which for us is far more familiar.

These predictions turn out to be correct (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977;

Figure 13.29).

SIMILARITY

Another

important factor that influences attraction is similarity, but in which direction does the effect run? Do “birds

of a feather flock together” or—perhaps in analogy with magnets—do “opposites

attract”? Birds have more to teach us in this matter than do magnets—the

evidence suggests that, in general, people tend to like others who are similar

to themselves (Figure 13.30). For example, elementary school students prefer

other children who perform about as well as they do in academics, sports, and

music (Tesser, Campbell, & Smith, 1984), and best friends in high school

tend to resemble each other in age, race, year in school, and grades (D. B.

Kandel, 1978).

Often

people who attract each other do differ in important personality characteris-tics,

so that an unaggressive person might be attracted to someone relatively

aggressive. On other dimensions, though, similarity is crucial. For example,

attributes such as race, ethnic origin, social and educational level, family

background, income, and religion do affect attraction in general and marital

choice in particular. Also relevant are behavioral patterns such as the degree

of gregariousness and drinking and smoking habits. One widely cited study

showed that engaged couples in the United States tend to be similar along all

of these dimensions (Burgess & Wallin, 1943), a pattern that provides

evi-dence for homogamy—a powerful

tendency for like to select like.

What

produces the homogamy pattern? One possibility is that similarity really does

lead to mutual liking, so that homogamy can be taken at face value. A different

possi-bility, though, is that similarity does not matter on its own; instead,

the apparent effects of similarity may be a by-product of proximity, of the

fact that “few of us have an opportunity to meet, interact with, become

attracted to, and marry a person markedly dissimilar from ourselves”. The

answer is uncertain, but in either case, the end result is the same. Like pairs

with like, and heiresses rarely marry the butler except in the movies. We are

not really surprised when a princess kisses a frog and he turns into a prince.

But we would be surprised to see the frog turn into a peasant and then see the

princess marry him anyway.

Related Topics