Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Relations: Helping and Altruism

Helping and Altruism

One

of our great sources of pride as a species is our ability to exhibit prosocial behav-iors, behaviors that

help others—assisting them in their various activities, supporting and aiding

them in their time of need. But, of course, we don’t always help. Sometimes we

ignore the homeless man as we walk by him; sometimes we throw away a charity’s

fundraising plea; sometimes we scurry past the person who has just dropped his

groceries. The question we need to ask, then, is why we sometimes help and

sometimes don’t. The answer, once again, involves a mix of factors—including

our personalities (whether we tend to be helpful overall) and our social

environment.

THE BY

STANDER EFFECT

Consider

the case of Kitty Genovese, who was attacked and murdered one early morn-ing in

1964 on a street in Queens, New York (Figure 13.24). While the details of the

case are disputed (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007), it is clear that the

assault lasted over half an hour, during which time Genovese screamed and

struggled while her assailant stabbed her repeatedly. Many of her neighbors

could see or hear her struggle but did not come to her aid. Why not? Why, in

general, do we often fail to help those who are obviously in need—perhaps even

in extreme danger?

According

to Latané and Darley, the failure to help is often produced by the way peo-ple

understand the situation. It’s not that people don’t care. It’s that they don’t

under-stand what should be done because the situation is ambiguous. In the

Genovese case, witnesses later reported that they were not sure what was

happening. Perhaps it was a joke, a drunken argument, a lovers’ quarrel. If it

were any of these, intervention might have been very embarrassing.

The

situation is further complicated by the fact that the various witnesses to the

Genovese murder realized that others were seeing or hearing what they did. This

circumstance created pluralistic

ignorance. Each of the witnesses was uncertain whether there really was an

emergency, and each looked to the others, trying to decide. Their rea-soning

was simple: “If my neighbors don’t react, then apparently they’ve decided

there’s no emergency, and, if there’s no emergency, there’s no reason for me to

react.” The tragedy, of course, is that the neighbors were thinking roughly the

same thoughts—with the consequence that each took the inactivity of the others

as a cue to do nothing.

Even

when people are convinced that they

are viewing an emergency, the presence of multiple bystanders still has an

effect. It creates a diffusion of responsibility,

with each bystander persuaded that someone else will respond to the emergency,

someone else will take the responsibility. This effect is illustrated by a

study in which participants were asked to join in what they thought was a group

discussion about college life with either one, three, or five other people.

Participants sat in individual cubicles and took turns talking to each other

over an intercom system. In actuality, though, there was only one participant;

all the other speakers were voices on a previously recorded tape. The

discussion began as one of these other speakers described some of his personal

prob-lems, which included a tendency toward epileptic seizures in times of

stress. When he began to speak again during the second round of talking, he

seemed to have a seizure and gasped for help. At issue was what would happen

next. Would the actual partici-pant take action to help this other person

apparently in distress?

The

answer was powerfully influenced by the “crowd size.” If the participant

believed that she had been having just a two-way discussion (so that there was

no one else around to help the person in distress), she was likely to leave her

own cubicle to help. But if the participant thought it was a group discussion,

a diffusion of responsibility occurred, and the larger the group the

participant thought she was in, the less likely she was to come to the victim’s

assistance (Darley & Latané, 1968).

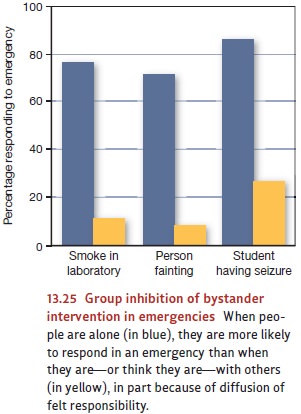

This

bystander effect has been

demonstrated in numerous other situations. In some, an actor posing as a fellow

participant seems to have an asthma attack; in others, someone appears to faint

in an adjacent room; in still others, the laboratory fills with

smoke.

Whatever the emergency, the result is always the same. The larger the group the

participant is in (or thinks he is in), the smaller the chance that he will

take any action (Latané & Nida, 1981; Latané, Nida, & Wilson, 1981;

Figure 13.25).

One

important qualification, however, is that larger (perceived) groups seem to

breed less helping only when the group members are strangers. When group

mem-bers are familiar others, larger group size can actually encourage helping

behavior (M. Levine & Crowther, 2008). But this, too, makes sense if we

consider the costs of not helping and

the benefits of helping. First, your

not taking action shifts the burden to someone else in the crowd—and if that

other person is someone you’re familiar with, you may feel uncomfortable

imposing on them in this way. Second, there’s likely to be some embarrassment

at not helping in an emergency situation, and that embarrassment grows if you

are with people you will be seeing again. Finally, taking action among friends

has the benefit of enhancing social cohesion and increasing a sense of pride in

group membership. Whether among strangers or friends, then, it appears that the

social setting guides your actions.

THE COST OF HELPING

Our

last example highlighted some of the costs of not helping, but there is also often a cost of helping—and both of

these costs shape our behavior. In some cases, the cost of helping lies in

physical danger—if, for example, you need to leap into an icy river to help

someone who is drowning. In others, the cost is measured simply in time and

effort. In all cases, though, the pattern is simple. The greater the cost of

helping and the smaller the cost of not helping, the smaller the chance that a

bystander will offer help to someone in need.

In

one study, for example, students had to go one at a time from one campus

build-ing to another to give a talk. They were told to hurry, since they were

already late. As students rushed to their appointments, they passed a shabbily

dressed man lying in a doorway groaning. Only 10% of the students stopped to

help this disguised confeder-ate. Ironically, the students were attending a

theological seminary, and the topic of their talk was the parable of the Good

Samaritan who came to the aid of a man lying injured on a roadside (Figure

13.26). It appears that if the cost—here in time—is high enough, even

theological students may not behave altruistically (Darley & Batson, 1973).

What is costly to one potential helper may not be equally so to another, however. Take physical danger. It is probably not surprising that bystanders who intervene in assault cases are generally much taller, stronger, and better trained to intervene than bystanders who do not intervene, and they are almost invariably men (Eagly & Crowley, 1986; Huston, Ruggiero, Conner, & Geis, 1981).

In

addition, the costs of providing help are sometimes weighed against the benefits of helping. Some of the

benefits are various signs of social approval, as with a donor to charity who

is sure to make a lavish contribution so long as everyone knows. A differ-ent

benefit is one we alluded to earlier—namely, the avoidance of shame or

embarrass-ment. Many city dwellers give 50 or 75 cents to a homeless person,

for example, not because they want to help but because it would be embarrassing

just to say no. Occasionally, the benefits of giving involve sexual attraction.

In one study, the investi-gators posed as motorists in distress trying to flag

passing cars to provide help with a flat tire. The passing cars were much more

likely to stop for a woman than for a man, and the cars that stopped were

generally driven by young men alone. The best guess is that the young men’s

altruism was not entirely unalloyed by sexual interest (West, Whitney, &

Schnedler, 1975).

One

additional factor that shapes whether people help each other is their cultural

context. Compared to Hindu Indians, for example, European Americans are less

likely to see that they have a moral imperative to help someone if they do not

like that person (J. G. Miller & Bersoff, 1998). European Americans also

see less of a moral imperative to help someone who has helped them in the past

(J. G. Miller, Bersoff, & Harwood, 1990). And because of the cultural

emphasis on taking care of “number one,” Americans will say that they are

acting out of self-interest, even when they are not (D. T. Miller, 1999).

Overall, these findings suggest that cultural emphasis on self-reliance and

self-interest may cause Americans and other members of individualistic

societies to think twice before helping, while the cultural emphasis on

relationships and connection may cause members of collectivistic societies to

offer aid more readily.

ALTRUISM AND SELF - INTEREST

The

preceding discussion suggests a somewhat unflattering portrait of human nature,

especially for those of us in individualistic cultures. It seems that we often

fail to help strangers in need, and when we do, our help is rather grudging and

calculated, based on some expectation of later reciprocation. But that picture

may be too one-sided. For while people can be callous and indifferent, they are

also capable of true generosity and even, at times, of altruism, or helping behavior that does not benefit the helper

(Figure 13.27). People share food, give blood, contribute to charities,

volunteer at AIDS hospices, and resuscitate accident victims. Even more

impressive are the unselfish deeds of living, genetically unrelated donors who

give one of their kidneys to a stranger who would oth-erwise die (Sadler,

Davison, Carroll, & Kounts, 1971). Consider too those commemorated by

Jerusalem’s Avenue of the Righteous—the European Christians who sheltered Jews

during the Holocaust, risking (and often sacrificing) their own lives to save

those to whom they gave refuge (London, 1970).

Why

do people engage in these activities? When asked, most report that such

altruistic actions make them better people (Piliavin & Callero, 1991; M.

Snyder & Omoto, 1992), and the major texts of all major religions support

this idea (Norenzayan & Shariff, 2008). Such acts of altruism suggest that

human behavior is not always selfish. To be sure, acts of altru-ism in which

the giver gets no benefits at all—no gratitude, no public acclaim—are fairly

rare. The true miracle is that they occur at all.

Related Topics