Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Cognition: Attribution

Attribution

People

everywhere spend a lot of time and energy observing the people around them and

asking , “ Why did she (or he) do that?” Social psychologists call the process

of answering this question causal

attribution, and the study of how people form attri-butions is one of

social psychology ’s central concerns (see, for example, F. Heider, 1958; E. E.

Jones, & Nisbett, 1972; H. H. Kelley, 1967; H. H. Kelley & Michela,

1980). As we saw, thinking about the world often requires us to go beyond the

information we are actually given. We interpret the visual images on our

retinas, for example, by using top-down knowledge to supplement what we see. We

draw inferences from the observations we make, to reach broader conclusions

about the world. As we will see, similar intellectual activity is essential in

the social domain.

ATTRIBUTION ASLAY SCIENCE

People

make attributions in roughly the same way that scientists track down the causes

of physical events (H. H. Kelley, 1967). For a scientist, an effect (such as an

increase in gas pressure) is attributed to a particular condition (such as a

rise in temperature) if the effect occurs when the condition is present but

does not occur when the condition is absent. In other words, the scientist

needs to know whether the cause and the effect covary. According to social

psychologist Harold Kelley, when people try to explain the behavior of others,

they use a similar covariation principle.

This

means that, to answer the question “Why did Mary smile at me?” we have to

consider when Mary smiles. Does she smile consistently whenever you walk into

the room? Does she refrain from smiling when others arrive? If the answer to

both of these questions is yes, then her smile does covary with your arrival,

and so is probably best understood as a result of her feelings about you. If it

turns out, though, that Mary smiles just as broadly when greeting others, then

we have to come up with a different explanation (F. Heider, 1958; H. H. Kelley,

1967).

Causal

attributions can be divided into two broad types—those that focus on factors

external to the person (e.g., Mary smiled because the situation demanded that

she be polite) and those that focus on the person herself (e.g., Mary smiled

because she is friendly). Explanations of the first type are called situational attributions and involve

factors such as other people’s expectations, the presence of rewards or

punishments, or even the weather. Explanations of the second type, dispositional attributions, focus on

factors that are internal to the person, such as traits, preferences, and other

personal qualities (Figure 13.1).

CULTURE

AND

ATTRIBUTION

How

do people choose attributions for the behaviors they observe? Kelley ’s

proposal was that people are sensitive to the evidence they encounter, just as

a scientist would be, and draw their conclusions according to this evidence. It

turns out, how-ever, that this is not quite right, because people have strong

biases in the way they interpret the behavior of others, biases that can

sometimes lead them to overrule the evidence. These biases come from many

sources, including the culture in which someone lives.

Every

person is a part of many cultures—those defined by race, nationality, and

ethnicity, and also those defined by gender, socioeconomic status, sexual

preference, urbanicity (e.g., city dwelling or rural dwelling), economy (e.g.,

agricultural or industrial), and historical cohort (e.g., baby boomer or gen

Xer). This diversity means that cultures differ on many dimensions, but there

is reason to believe that one dimension is especially important—whether a

culture is more individualistic or more collectivistic (Triandis, 1989, 1994).

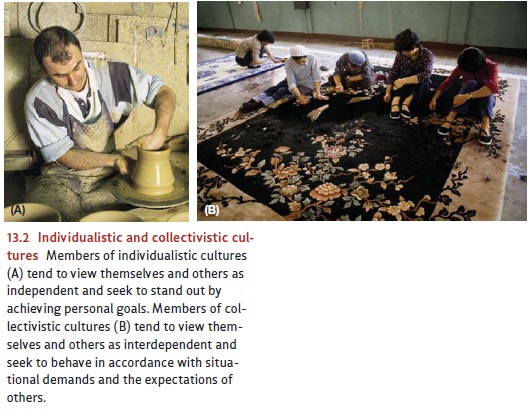

As

the name suggests, individualistic

cultures cater to the rights, needs, and preferences of the individual. The

majority cultures (e.g., middle-class, of European her-itage) of the United

States, western Europe, Canada, and Australia are individualistic (Figure

13.2). In these cultures, people tend to view themselves and others as

independent entities—that is, as fundamentally separate from others and their

environ-ment. They also generally think that people behave according to their

internal thoughts, feelings, needs, and preferences (A. P. Fiske, Kitayama,

Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; Markus & Kitayama, 1991), and not according to

outside influences, such as other people’s expec-tations or the demands of a

situation. To emphasize their independence and distinctive-ness, people in

individualistic cultures often strive to stand out by achieving personal goals.

They still feel obligated to their families and communities, but regularly

override these social obligations in order to pursue their own paths.

Collectivistic cultures, on the other hand, stress the importance of maintainingthe norms, standards, and traditions of families and other social groups. Most of the world’s cultures are collectivistic, including many of those of Latin America, Asia, and Africa. In collectivistic cultures, people tend to view themselves and others as interdependent—that is, as fundamentally connected to the people in their immedi-ate community and to their environment. They usually think that people behave according to the demands of a situation or the expectations of others, and not according to their personal preferences or proclivities. People still have their own dreams, desires, and life plans, of course, but they are more likely to create those plans according to the wishes and expectations of others, and to change them when the situation demands.

It

bears emphasizing that not everyone in collectivistic cultures has an

interdependent notion of the person, just as not everyone in individualistic

cultures has an independent notion. Instead, these terms describe what is

typical, as well as what each culture’s traditions, laws, religions, schools,

and media encourage.

THE FUNDAMENTAL ATTRIBUTION ERROR

These

differences among cultures influence us in many ways—including the ways we

think about other people’s behavior. In particular, people from

indi-vidualistic cultures routinely ascribe others’ behavior to dispositions

and not to situations—even when there is ample reason to believe that

situations are playing a crucial role (Figure 13.3). Thus North Americans of

European her-itage tend to see people on public assistance as lazy (a

dispositional attri-bution), for example, rather than struggling in an economy

with high unemployment and few entry-level positions (a situational

attribu-tion). Likewise, members of these cultures tend to view poor performance

on a test as a sign of low

intelligence(disposition) rather than as a result of an overly difficult exam

(situation). Thisbias is so pervasive that it is called the fundamental attribution error(D.T. Gilbert & Malone, 1995; L . Ross, 1977;

Sabini,Siepmann, & Stein, 2001).

To

dramatize this error, one early study had American college students

partici-pate in a simulated TV quiz show. Students were run in pairs and drew

cards to decide who would be the “quizmaster” and who the “contestant.” The

quizmaster had to make up questions, drawn from any area in which she had some

expertise; the contestant had to try to answer these questions. The game then

proceeded, and, inevitably, some of the quizmasters’ questions were extremely

difficult (e.g., “What do the initials W.

H. stand for in the poet W. H. Auden’s name?”).* A student audience watched

and subsequently rated how knowledgeable the two participants were.

The

situation plainly favored the quizmasters, who could choose any question or

topic they wished. Hence, if a quizmaster had knowledge of just one obscure

topic, he could focus all his questions on that topic, without revealing that

he had little knowledge in other domains. The contestants, on the other hand,

were at the mercy of whatever questions their quizmaster posed. Any

interpretation of the quizmasters’ “superiority” should take this obvious

situational advantage into account. But theobservers consistently failed to do

this. They knew that the roles in the setting—who was quizmaster, who was

contestant—had been determined by chance, for they had witnessed the entire

procedure. Even so, they could not help regarding the quizmas-ters as more

knowledgeable than the contestants—a tribute to the power of the fun-damental

attribution error (L .Ross, Amabile, & Steinmetz, 1977).

The

pattern of attributions is quite different, though, in collectivistic cultures.

In one study, Hindu Indians and European Americans were asked to discuss

vignettes about other people’s actions. Consistent with other research, the

European Americans’ comments included twice as many dispositional explanations

as situational explana-tions. The Hindu Indians showed the opposite pattern.

They gave twice as many situa-tional explanations as dispositional

explanations. As an illustration, one of the vignettes used in the study

described an accident in which the back wheel of a motor-cycle burst, throwing

the passenger off the motorcycle, and the driver had done little to help the

hurt passenger. Overall, the Americans typically described the driver as

“obvi-ously irresponsible” or “in a state of shock,” whereas the Indians

typically explained that it was the driver’s duty to be at work or that the

other person’s injury must not have looked serious (J. G. Miller, 1984; see

also A. P. Fiske et al., 1998; Maass, Karasawa, Politi, & Suga, 2006; P. B.

Smith & Bond, 1993).

Related Topics