Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Influence: Group Dynamics

Group Dynamics

So

far, we have described social influence as though it were a “one-way street.”

The group presses you toward conformity. A salesperson leads you toward a

concession. But, of course, social interactions often involve mutual

influence—with each person in the group having an impact on every other person

in the group. The study of this sort of interaction is the study of group dynamics.

MERE PRESENCE EFFECTS

More

than a century ago, Triplett noticed that cyclists performed better when they

competed against others than when they competed against the clock (Triplett,

1898; Figure 13.20). This observation inspired him to conduct one of social psychology’s

first experiments, in which he told children to turn a fishing reel as quickly

as they could, either alone or with another child. Triplett found that children

turned the reel more quickly when they were with others than when they were

alone.

This

finding was subsequently replicated many times, and initial results suggested

that this mere presence effect was

uniformly beneficial. For example, when working alongside others who are

engaged in the same task, people learn simple mazes more

quickly

and perform more multiplication problems in the same period of time—

illustrations of a pattern known as social

facilitation (F. H. Allport, 1920). Other stud-ies, however, show that the

presence of others can sometimes hinder rather than help—an effect called social inhibition. While college

students solve simple mazes more quickly when working with others, they are

considerably slower at solving more complex mazes when others are around (Hunt

& Hillery, 1973; Zajonc, 1965, 1980). How can we reconcile such divergent

results?

Zajonc

(1965) argued that the presence of other people increases our level of bod-ily

arousal, which strengthens the tendency to perform highly dominant responses—

the ones that seem to come automatically. When the dominant response is also

the correct one, as in performing simple motor skills or learning simple mazes,

social presence should help. But when the task gets harder, as in the case of

complex mazes, then the dominant response is often incorrect. As a result,

performance gets worse when others watch, for in that case the dominant

response (enhanced by increased arousal) inhibits the less dominant but correct

reaction.

Evidence

supporting this view comes from a wide array of studies. In one study,

researchers observed pool players in a college union building. When good

players competed in front of an audience of four others, their accuracy rose

from 71 to 80%. But when poor players were observed, their accuracy dropped from

35 to 25% (Michaels, Bloomel, Brocato, Linkous, & Rowe, 1982). Similar

effects can be observed even in organisms very different from humans. In one

study, cockroaches learned to escape from a bright light by running down a

simple alley or by learning a maze. Some performed alone; others ran in pairs.

When in the alley, the cockroaches performed better in pairs than alone—for

this simple task, the dominant response was appro-priate. In the maze, however,

they performed better alone; for this more complex task, the dominant response

was incorrect and inappropriate (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969).

SOCIAL LOAFING

The

studies just described are concerned with people working independently of each

other or people working in the presence of an audience. But what about people

work-ing together—such as a committee working on an administrative project, or

a group of students working on a class project? In cases like these, everyone

is a performer and an audience member, because every member of the group is contributing

to the overall product. Likewise, everyone is able to see and perhaps evaluate

others’ contributions. How do group members influence each other in this

setting?

In

this situation, we are likely to observe a phenomenon known as social loafing (Latané, 1981), a

pattern in which individuals working together in a group generate less total

effort than they would if each worked alone. In one study, individual men were

asked to pull on a rope; the average force for these pulls was 139 pounds. When

groups of eight pulled together, the average was 546 pounds—only about 68

pounds per per-son. In another study, students were asked to clap and cheer as

loudly as they could, sometimes alone, sometimes in groups of two, four, or

six. Here, too, the results showed social loafing. Each person cheered and

clapped less vigorously the greater the number of others she was with (Latané,

Williams, & Harkins, 1979). This general finding that individuals work less

hard in groups has now been replicated many times in the United States, India,

and China (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Why do individuals work less hard in groups? One reason is that

they may feel less accountable and therefore are less motivated to try as hard

as they can. Another reason is that they may think that their contribution is

not crucial to group success (Harkins Szymanski, 1989). There is an old adage:

“Many hands make light work.” The trou-ble is that they do not always make it

as light as they could.

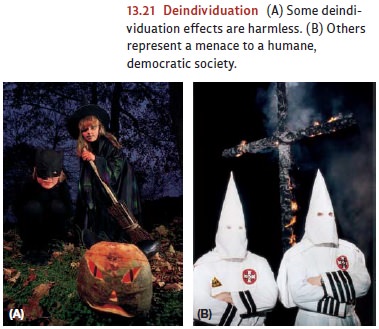

DEINDIVIDUATION

Apparently,

then, the presence of others can influence us in multiple ways—in some

circumstances facilitating our behavior, and in other circumstances inhibiting

us. But the presence of others can also dramatically change how we act. In a

riot or lynch mob, for example, people express aggression with a viciousness

that would be inconceivable if they acted in isolation. A crowd that gathers to

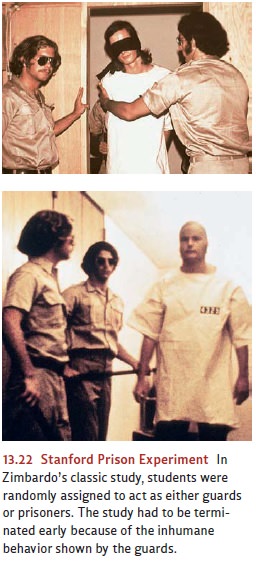

watch a disturbed person on a ledge atop a tall building often taunts the

would-be suicide, urging him to jump. What does being in a crowd do to people

to make them act so differently from their everyday selves?

One

perspective on these questions describes crowd behavior as a kind of mass

mad-ness. This view was first offered by Le Bon (1841–1931), a French social

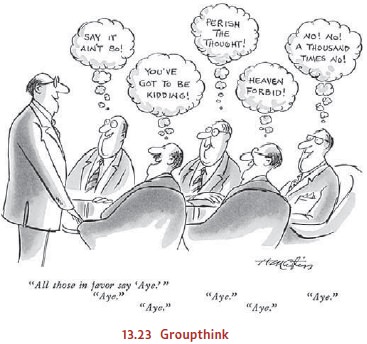

psychologist who contended that people in crowds become wild, stupid, and

irrational and give vent to primitive impulses. He believed their emotion

spreads by a sort of contagion, rising to an ever-higher pitch as more and more

crowd members become affected. Thus, fear becomes terror, hostility turns into

murderous rage, and each crowd member becomes a barbarian—“a grain of sand

among other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will” (Le Bon, 1895).

Many

modern psychologists believe that although Le Bon may have overstated his case,

his claims contain an important truth. To them, the key to crowd behavior is dein-dividuation, a state in which an

individual in a group loses awareness of herself as aseparate individual

(Figure 13.21). This state is more likely to occur when there is a high level

of arousal and anonymity—just as would be the case in a large and angry crowd

or a large and fearful gathering. Deindividuation tends to release impulsive

actions that are normally under restraint, and what the impulses are depends on

the group and the situation. In a carnival, the (masked) revelers may join in

wild orgies; in a lynch mob, the group members may torture or kill (Diener,

1979; Festinger, Pepitone, & Newcomb, 1952; Zimbardo, 1969).

To

study deindividuation, one investigation had college students wear identical

robes and hoods that made it impossible to identify them. Once in these hoods—

which, not coincidentally, looked just like Ku Klux Klan robes—the students

were asked to deliver an electric shock to another person; they delivered twice

as much shock as those not wearing the robes (Zimbardo, 1970). In the robes, it

seemed, the students felt free to “play the part”—and in this case the result

was ugly. Other stud-ies, though, reveal the good that can be produced by

deindividua-

tion.

In a different experiment, students were asked to wear nurses’ uniforms rather

than KKK costumes; dressed in this way, students delivered less shock than a

group without costumes (R . D. Johnson & Downing, 1979). Thus,

deindividuation by itself is not bad—it simply makes it easy for us to give in

to the impulses cued by the sit-uation, and the nature of those impulses

depends on the circum-stances.

Notice

also that deindividuation can happen in several different ways. Being in a

large crowd produces deindividuation; this is part of why mobs act as they do.

Wearing a mask can also produce dein-dividuation, largely because of the

anonymity it provides. But dein-dividuation can also result merely from

someone’s wearing a uniform and having an assigned role—in essence, he

“becomes” the

role.

This third factor was plainly revealed in a classic study known as the StanfordPrison Experiment, in which

Philip Zimbardo transformed the basement of StanfordUniversity’s psychology

department into a mock prison and randomly assigned male undergraduate

participants to the role of either guards or prisoners (Figure 13.22; Haney,

Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973; Zimbardo, 1973; see also Haney & Zimbardo,

1998). Guards and prisoners wore uniforms appropriate to their roles, and

prisoners were called by assigned numbers instead of their names. The

experimenter gave the partic-ipants few instructions, and placed few

constraints on their behavior. What rapidly evolved was a set of behaviors

remarkably similar to those sometimes observed in actual prisons—with cruelty,

inhumane treatment, and massive disrespect evident in all the participants. The

behaviors observed were sufficiently awful that Zimbardo ended his study after

only 6 days, before things got really out of hand, rather than let-ting it run

for 2 weeks, as was originally planned.

Sadly,

the powerful effects of deindividuation and stepping into a role extend well

beyond the confines of the laboratory setting. As we saw, one now-infamous

real-world example is the abusive behavior exhibited by military personnel at

Abu Ghraib prison. In the face of worldwide condemnation, Americans of all

stripes struggled to understand how their own countrymen and countrywomen could

behave in such an unconscionable fashion. Mindful of the lessons of the

Stanford Prison Experiment, though, Zimbardo and other social psychologists

have argued that powerful social forces were at work here that included—among

others— the power of deindividuation through reducing people to their roles

(Zimbardo, 2007). As a result, the situation itself may have done far more to

create these abuses than the personal qualities of any of the soldiers

involved.

GROUP POLARIZATION

Being

in a group doesn’t just influence our behavior; it also influences our

thoughts— and often for the worse. For example, consider the phenomenon of group polarization, a tendency for

group decisions to be more extreme than the decisions that would have been made

by any of the members on their own. This pattern arises in many different group

contexts, such as when juries decide how much money to award a plaintiff at the

end of a lawsuit.

Often

the polarization takes the form of a so-called risky shift, in which groups appear more willing to take risks, or

more willing to take an extreme stance, than the group members would be

individually (Bennett, Lindskold, & Bennett, 1973; C. P. Morgan & Aram,

1975; Schroeder, 1973). However, group polarization can also take the opposite

form. If the group members are slightly cautious to begin with or slightly

con-servative in their choices, then these tendencies are magnified, and the

group’s decision will end up appreciably more cautious than the decisions that

would have been made by the individuals alone (Levine & Moreland, 1998;

Moscovici & Zavalloni, 1969).

What

produces group polarization? One factor is the simple point that, during a

dis-cussion, individuals often state, restate, and restate again what their

views are, which helps to strengthen their commitment to these views (Brauer,

Judd, & Gliner, 1995). Another factor involves the sort of confirmation

bias that we discussed— the fact that people tend to pay more attention to, and

more readily accept, information that confirms their views, in comparison to

their (relatively hostile) scrutiny of information that challenges their views.

How does this shape a group discussion? In the discussion, people are likely to

hear sentiments on both sides of an issue. Owing to confirmation bias, the

arguments that support their view are likely to seem clear, persuasive, and

well informed. Opposing arguments, however, will seem weak and ambiguous. This

allows people to conclude that the arguments favoring their view are strong,

while the counterarguments are weak, which simply strengthens their commit-ment

to their own prior opinion (for the classic example of this pattern, see C. G.

Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979; also Kovera, 2002).

Another

factor leading to group polarization hinges on two topics we have already

mentioned. On the one hand, people generally try to conform with the other

mem-bers of the group, both in their behavior and in the attitudes they

express. But, in addition, people in individualistic cultures want to stand out

from the crowd and be judged “better than average.” How can they achieve both

of these goals—conform-ing and excelling? They can take a position at the

group’s “leading edge”—similar enough to the group’s position so that they have

honored the demands of conform-ity, but “out in front” of the group in a way

that makes them seem distinctive. Of course, the same logic applies to everyone

in the group, so everyone will seek to take positions and express sentiments at

the group’s leading edge. As a result, this edge will become the majority view!

In this way, right at the start the group’s sentiments will be sharpened and

made a step or two more extreme—exactly the pattern of group polarization.

GROUP THINK

Group

decision making also reveals a pattern dubbed groupthink (Janis, 1982). This pattern is particularly likely when

the group is highly cohesive—such as a group of friends or people who have

worked together for many years—and when the group is facing some external

threat and is closed to outside information or opinions. In this setting, there

is a strong tendency for group members to do what they can to promote the sense

of group cohesion. As a result, they downplay doubts or disagreements,

celebrate the “moral” or “superior” status of the group’s arguments, stereotype

enemies (“our opponents are stupid” or “evil”), markedly overestimate the

likelihood of success, and dis-count or ignore risks or challenges to the group

(Figure 13.23).

Arguably,

groupthink caused a number of disastrous decisions, including the U.S.

government’s decision to invade Cuba in the early 1960s (Janis, 1971) and the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration’s decision to launch the Challenger on a cold day in 1986 despite

the knowledge that one part of the space shuttle did not perform well at very

cold temperatures (Moorhead, Ference, & Neck, 1991). Social psychologists

are still working to understand exactly when the groupthink pattern emerges and

what steps can be taken to limit the negative effects of groupthink on decision

making (Kruglanski, Pierro, Mannetti, & De Grada, 2006; Packer, 2009).

Related Topics