Chapter: Psychology: Social Psychology

Social Cognition: Attitudes

Attitudes

As

we have now seen, our relations with the people who surround us depend to a

large extent on our beliefs. These

beliefs include our assumptions about how others’ behavior should be

interpreted, and our beliefs about how the various attributes in someone’s

personality fit together, and also our beliefs about Jews, or African

Americans, or the Irish. Moreover, these beliefs are not just “cold”

cognitions—dispassionate assertions about the world. Instead, they are often

“hot,” in the sense that they have motivational components and can trigger (and

be triggered by) various emotions. Psychologists refer to these beliefs as attitudes.

People

have attitudes about topics as diverse as the death penalty, abortion,

bilingual education, the importance of environmental pro-tection, and need for

civility in everyday social interaction (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). The belief

that defines each attitude is almost inevitably associated with emotional

feelings and a predisposition to act in accordance with the belief and

feelings. Thus, people who dif-fer in their attitudes on abortion are certain

to have different beliefs about the moral status of this procedure, but also

will have different feelings about the family planning clinic they pass every

day, and dif-ferent levels of commitment to showing up at a rally protesting

their state’s abortion laws (Figure 13.6).

ATTITUDE FORMATION

How

do attitudes arise? Some of our attitudes are based on our consideration of the

facts. We carefully weigh the pros and cons of an argument and make up our

minds about whether we should endorse the argument’s conclusion or not. In many

other cases, however, the sources of our attitudes are not quite so rational.

Sometimes

we acquire our attitudes through one of the forms of learning. In some cases,

the learning is akin to classical

conditioning. For exam-ple, we might repeatedly see a brand of cigarettes

paired with an appealing person or a cool cartoon character and wind up

associating the two, leaving us with a positive atti-tude toward that brand of

cigarettes (Figure 13.7; Cacioppo, Marshall-Goodell, Tassinary, & Petty,

1992). In other cases, attitudes can be formed via a process akin to operant conditioning, when, for example,

parents reward behavior they would like toencourage, such as hard work at

school and good table manners. The end result of this

training,

in many cases, is a favorable attitude toward certain work habits and certain

forms of etiquette. In still other cases, attitudes emerge from a sort of observationallearning. We see a

respected peer endorse a particular attitude, or we observe someonebenefit from

an attitude. In either case, we may then to endorse the attitude ourselves.

ATTITUDE CHANGE : BEING PERSUADED BY OTHERS

What

happens once we form an attitude? In many cases, we are bombarded by messages

exhorting us to change the attitude; sometimes these messages are effective and

some-times not. Sometimes a TV commercial persuades us to switch our brand of

toothpaste, but other times we remain loyal to our usual brand. Sometimes a

politician persuades us to change our vote, but other times we hold our ground.

Examples like these lead us to ask, When do attitudes change, and when do they

stay the same?

To

answer this question, we need to make a crucial distinction between two types

of persuasion, each based on a different mode of processing information (Petty

& Briñol, 2008). In the central

route to persuasion, we carefully track the information we receive and

elaborate its arguments with considerations of our own. We take this route if

the issue matters to us and if we are not diverted by other concerns. In this

case, we are keenly sensitive to the credibility and trustworthiness of the

message’s source (Aronson, Turner, & Carlsmith, 1963; Hovland and Weiss,

1952; Walster, Aronson, & Abrahams, 1966). We also pay close attention to

the content of the persuasive message, and so—sensibly—strong arguments will be

more effective in changing our mind than weak ones.

The

situation is different, though, if a message comes by way of the peripheral routeto persuasion. Here, we

devote far fewer cognitive resources to processing incominginformation. We use

this mode of information processing if we do not care much about an issue or if

we are distracted. In such circumstances, content and arguments matter little.

What counts instead is how and by whom the message is presented (Petty &

Briñol, 2008; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997;

for a closely related view, see Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989). Thus, we

are likely to be persuaded by an attractive and charismatic spokesperson

offering familiar catchphrases—even if she makes poor arguments (Figure 13.8).

ATTITUDE CHANGE : THE ROLE OF EXPERIENCE

Another

path to attitude change is direct experience with the target of one’s attitude.

This path has been particularly relevant in attempts to change prejudice toward

the members of a particular group. In one early study of this issue, twenty-two

11- and 12-year-old boys took part in an outdoor program at Robbers Cave State

Park in Oklahoma (so named because Jesse James was said to have hidden out

there). The boys were divided into two groups, each of which had its own

activities, such as baseball and swimming. Within a few days the two groups—the

Eagles and the Rattlers—had their own identities, norms, and leaders. The

researchers then began to encourage intergroup rivalry through a competitive

tournament in which valuable prizes were promised to the winning side.

Relations between the two groups became increasingly hostile and even violent,

with food fights, taunts, and fist fights (Sherif, 1966; Sherif, Harvey, White,

Hood, & Sherif, 1961).

At this point, the researchers intervened and established goals for the boys that could be achieved only through cooperation between the two groups. In one instance, the researchers disrupted the camp’s water supply, and the boys had to pool their resources in order to fix it. In another instance, the camp truck stalled, and the boys had to team up to get it moving. By working together on goals they all cared about—but could achieve only through collective effort—the boys broke down the divisions that had previously dominated camp life and ended their stay on good terms.

More

recent studies have confirmed the implication of this study—namely, that

intergroup contact can have a powerful effect on attitudes about the other

group, espe-cially if the contact is sustained over a period of time, involves

active cooperation in pursuit of a shared goal, and provides equal status for

all participants (see, for example, Aronson & Patnoe, 1997; Henry & Hardin,

2006; Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Tropp & Pettigrew,

2005). We can also take steps to increase outgroup empathy (T. A. Cohen &

Insko, 2008) and to encourage the prejudiced person to develop an

individualized perception of the other group and so lose the “they’re all

alike” attitude (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1999).

ATTITUDE

CHANGE : PERSUADING OURSELVES

Yet

another route to attitude change is through our own behavior. At first, this

may seem odd, because common sense argues that attitudes cause behavior, and

not the other way around. But sometimes our own behaviors can cause us to

change our views of the world.

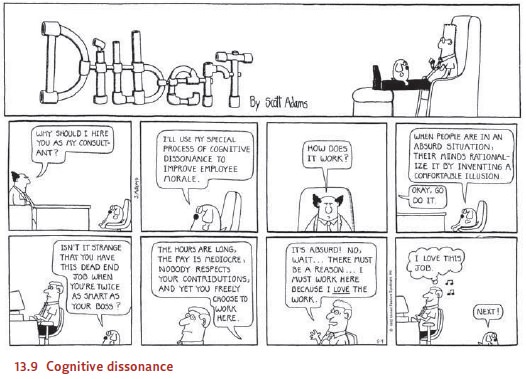

In

his classic work on this problem, Leon Festinger argued that people put a high

value on being consistent, so that any perceived inconsistency among their

beliefs, feelings, and behavior creates a very uncomfortable state of cognitive dissonance (Figure 13.9; J.

Cooper, 2007; Festinger, 1957, 1962; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999). How do

people escape this aversive state? In one study, Festinger and Carlsmith (1959)

asked participants to perform several extremely boring tasks, such as packing

spools into a tray and then unpacking them, or turning one knob after another

for a quarter turn. When they were finished, the participants were induced to

tell the next partici-pant that the tasks were very interesting. Half the

participants were paid reasonably well for this lie (they were given $20); the

others were given just $1. Later, when asked

how

much they enjoyed the tasks, the well-paid participants said that the tasks

were boring and that they understood that they had lied to the other

participants. In con-trast, the poorly paid participants claimed that the

monotonous tasks were fairly inter-esting, and that what they told the other

participants was the truth.

What

produces this odd pattern? According to Festinger, the well-paid liars knew why

they had mouthed sentiments they did not endorse: $20 was reason enough. The

poorly paid liars, however, had experienced cognitive dissonance, thanks to the

fact that they had misled other people without good reason for doing so. They

had, in other words, received insufficient

justification for their action. Taken at face value, this made them look

like casual and unprincipled liars, a view that conflicted with how they wanted

to see themselves. How could they reconcile their behavior with their

self-concept? One solution was to reevaluate the boring tasks. If they could

change their mind about the tasks and decide they were not so awful, then there

was no lie and hence no dissonance. Judging from the data, this is apparently

the solution that the partici-pants selected—bringing their attitudes into line

with their behavior.

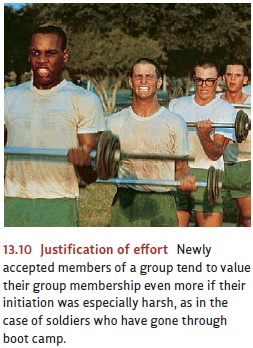

These

findings help make sense of why many organizations have difficult or aversive

entrance requirements (Figure 13.10). For example, many American college

fraternities have hazing rituals that are unpleasant and in some cases

humiliating or worse. Although these rituals may be objectionable, they do

serve a function. They lead new fraternity members to place a higher value on

their membership than they otherwise would. They know what they have suffered

to achieve membership, and it would create dissonance for them to believe that

they have suffered for no purpose. They can avoid this dissonance though, if

they are convinced that their membership is really valuable. In that case,

their suffering was “worth it.”

There

is no question about the data patterns associated with cognitive dissonance,

but many researchers have disagreed with Festinger over why the pattern

emerges. The most important challenge to Festinger’s account is Daryl Bem’s self-perception theory (1967, 1972).

According to this conception, there is no need to postulate the emotional

distress that allegedly accompanies cognitive dissonance and, according to

Festinger, propels atti-tude change. Instead, we can understand the data in

terms of the information available to the participants in these experiments.

Specifically, the research participants are simply try-ing to make sense of

their own behavior in much the same way that an outside observer might. Thus,

in the knob-turning study, self-perception theory would hold that a

partici-pant in the $1 condition would have known that $1 was insufficient

justification for lying and so would have concluded that he did not lie. On

this basis, if he said the task was fun and if he was not lying, then the task apparently

was fun.

This

line of interpretation makes sense of many other results as well. Consider

stud-ies of the so-called foot-in-the-door technique originally devised by

door-to-door salesmen. In one study, an experimenter asked suburban homeowners

to comply with an innocuous request, to put a 3-inch-square sign advocating

auto safety in a window of their home. Two weeks later, a different

experimenter came to visit the same home-owners and asked them to grant a much

bigger request, to place on their front lawn an enormous billboard that

proclaimed “Drive Carefully” in huge letters. The results showed that whether

people granted the larger request was heavily influenced by whether they had

earlier agreed to the smaller request. The homeowners who had com-plied with

the small request were much more likely to give in to the greater one (Freedman

& Fraser, 1966; although, for limits on this technique, see Burger &

Guadagno, 2003; Chartrand, Pinckert, & Burger, 1999).

According

to self-perception theory, the homeowners, having agreed to put up the small

sign, now thought of themselves as active citizens involved in a public issue.

“Why did I put up the sign? No one forced me to do it. I guess, therefore, that

this is an issue that I care about.” Thus, they interpreted their actions as

revealing a convic-tion that previously they did not know they had, and given

that they now thought of themselves as active, convinced, and involved, they

were ready to play the part on a larger scale. Fortunately for the neighbors,

the billboards were never installed—after all, this was an experiment. But in

real life we may not be so easily let off the hook, and the foot-in-the-door

approach is a common device for persuading the initially uncommitted.

ATTITUDE STABILITY

We’ve

now seen that attitudes can be changed in many ways—by certain forms of

persuasion (if the source is credible and trustworthy and if the message is

appropri-ate), by intergroup contact (in the case of prejudice), and by

tendencies toward cog-nitive consistency (especially with regard to acts we

have already performed). Given these points, and given all the many powerful

forces aimed at changing our attitudes, it might seem that our attitudes would

be in continual flux, changing from moment to moment and day to day. But on

balance, the overall picture is one of attitude sta-bility rather than attitude

change. Attitudes can be altered, but it takes some doing. By and large, we

seem to have a tendency to hold on to the attitudes we already have (Figure

13.11).

Why

should this be so? One reason for attitude stability is that people rarely make

changes in their social or economic environments. Their families, their friends

and fellow workers, their social and economic situations—all tend to remain

much the same over the years. All of this means that people will be exposed to

many of the same influences year in and year out, and this sameness will

obviously promote stability—in people’s beliefs, values, and inclinations.

Moreover, most of us tend to be surrounded by people with atti-tudes not so

different from our own. After all, top-level executives know other top

execu-tives, college students know other college students, and trade union

members know other union members. As a result, we are likely, day by day, to encounter

few challenges to our attitudes, few contrary opinions, and this, too, promotes

stability.

Of course, some events may transform attitudes completely—not just our own, but those of everyone around us. One example is the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Without a doubt, this led to an instant and radical change in Americans’ attitudes toward Japan. A more recent example is the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. These attacks dramatically increased Americans’ fear of terrorism and raised public support for a number of actions (including two wars that would never have unfolded if Americans had been less concerned about the country’s security). But by their very nature, such events—and the extreme changes in attitudes they produce—are rare.

Related Topics