Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Teleosts at last II:spiny-rayed fishes

Series Percomorpha:basal orders

Series Percomorpha:basal orders

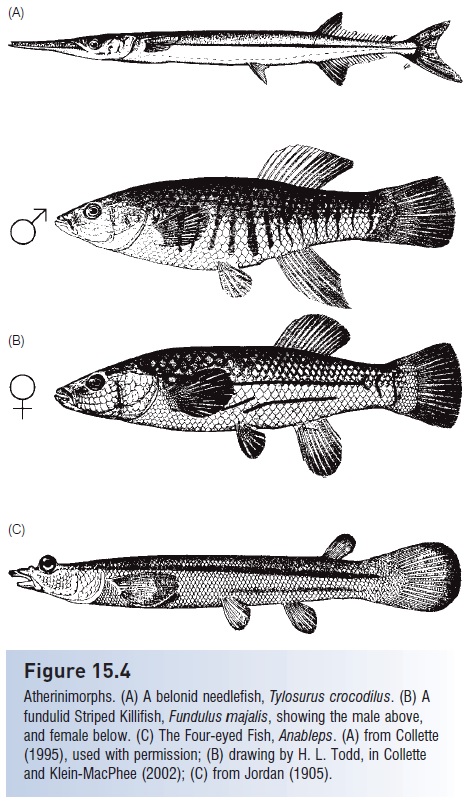

The cyprinodontid pupfishes are environmentally tolerantfishes that can live in water of highly variable salinity and temperature, characteristics that have allowed them to invade fluctuating environments such as saltmarshes, springs, and desert ponds. The isolated nature of many such habitats fuels rapid speciation but also makes the inhabitants extremely vulnerable to environmental disturbance; many pupfishes and their relativeshave been extinguished or currently have Critically Endangered status according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2004; see also www.desertfishes.org). Many species of Orestias have evolved in Andean lakes, including Lake Titicaca, which at 4570 m above sea level is the highest natural body of water populated by fishes. Anablepidfour-eyedfishes, a phylogenetically intermediate family within thecyprinodontiforms, is extraordinary in its eye structure(Fig. 15.4C). Four-eyed fishes are surface dwellers that swim with their protruding eyes half out of water. Thepupil of the eye itself is physically divided into dorsal andventral halves, the upper half capable of forming focused images of objects in air and the lower half simultaneouslyforming images of objects underwater (an intertidal labrisomid,the Galápagos four-eyed blenny, Dialommus fuscus,has converged on a similar eye structure). Some of thelive-bearing poeciliids are “species” that originated throughhybridization and today do not include functional males;females instead use males of other species to activateembryogenesis, male genetic material being excluded from future generations (Meffe & Snelson 1989; Houde 1997; Uribe & Grier 2005; Gender rolesin fishes). Poeciliids are an important ecological component of freshwater habitats on islands of the tropical western Atlantic and Caribbean, as well as coastal, tropical streams.

The most advanced euteleostean clade is the Percomorpha,a diverse and varied taxon that contains more than 13,000 species of largely marine families, although several successful freshwater groups also belong in this lineage. Percomorph have in common an anteriorly placed pelvic girdle

Figure 15.5

The Orange Roughy, Hoplostethus atlanticus, a trachichthyidberyciform. Photo by G. Helfman.

At the base of the percomorphs are two orders of eitherdeepsea or nocturnal fishes, the stephanoberyciform pricklefish taxa and the beryciform squirrelfish taxa. These large-headed, round fishes have many percomorph characteristics, except the tail fin has a primitivelylarge number of rays (18 or 19) as compared to the17 caudal rays that typify most advanced percomorphs. Theprimitivestephanoberyciforms (gibberfishes, pricklefishes,cetomimoid whalefishes) are largely deepsea forms characterizedby luminescent organs, weak or absent fin spines,and reduced squamation. Beryciforms often have the largeeyes typical of nocturnal fishes and possess strong spineson the head or gill covers. Included among the beryciformsre such relatively shallow water luminescent forms as pineconefishes and fl ashlight fishes, reef forms such as squirrelfishes, and the commercially important Orange Roughy,Hoplostethus atlanticus (Fig. 15.5). Beryciforms are wellrepresented in the fossil record, dating back to the LateCretaceous. Zeiforms are a confusing assortment of primitivemarine percomorphs that have highly protrusiblemouths and a unique caudal skeleton. Included in this orderare such commercial species as the European John Dory,Zeus faber.

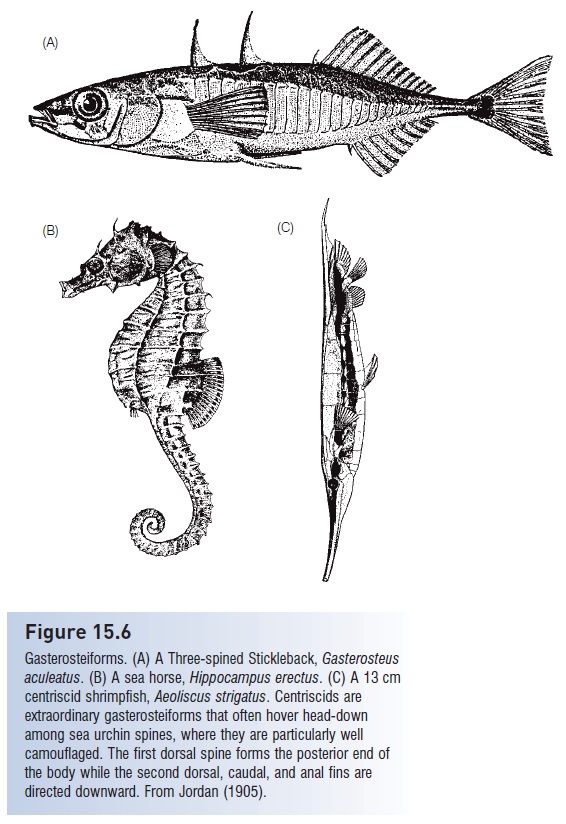

Figure 15.6

Gasterosteiforms. (A) A Three-spined Stickleback, Gasterosteusaculeatus. (B) A sea horse, Hippocampus erectus. (C) A 13 cmcentriscid shrimpfish,Aeoliscus strigatus. Centriscids areextraordinary gasterosteiforms that often hover head-downamong sea urchin spines, where they are particularly wellcamouflaged. The first dorsal spine forms the posterior end ofthe body while the second dorsal, caudal, and anal fins aredirected downward. From Jordan (1905).

.

Acanthopterygians as a group are not as well represented in the deep sea as are more primitive taxa. After the stephanoberyciformsand primitive beryciforms, few deepsea fishes occur. The most advanced beryciforms, such as thesquirrelfishes, are also the shallowest dwellers. It is possiblethat as more advanced clades arose within the Euteleostei,their specializations made them competitively superior toprimitive groups and the younger taxa displaced the olderout of productive shallow water habitats and into the lessproductive deepsea region. Alternatively, overriding trendswithin the Acanthopterygii include the development ofstout spines and other hard structures (bony skull crests,spined scales, dermal ossifi cations), which may have beendifficult to reverse. Since a common convergence amongdeepsea forms is the loss or reduction of hard body parts,acanthopterygians may have been phylogenetically constrainedfrom developing the energy-saving traits necessary for existence in the deep sea. Which is not to say thatdeepsea acanthopterygians are marginally successful in deep waters; the cetomimid flabby whale fishes are secondonly to the oneirodid anglerfishes (a paracanthopterygian)in species diversity among bathypelagic forms, and may exceed angler fishes in abudance in deeper waters. Interestingly, cetomimids have converged with angler fishes in having dwarf males, although whale fishes are not knownto be parasitic on the larger females.

Gasterosteiforms are generally small marine and freshwater fishes with dermal armor plates, small mouths, andunorthodox propulsion (Fig. 15.6). Sticklebacks are among the world’s most intensively studied fishes behaviorally,physiologically, ecologically, and evolutionarily (Wootton 1984; Bell & Foster 1994). Although only seven stickleback species are recognized, separate populations often divergein anatomical traits and may constitute distinct genomes.The extent of predator avoidance, spines, and dermal plates often vary in relation to the threat from predators experienced by a population, making them showcases of theevolutionary process, as is the repeated, independent appearance of species pairs in multiple lakes (e.g., Rundleet al. 2003; Boughman et al. 2005).

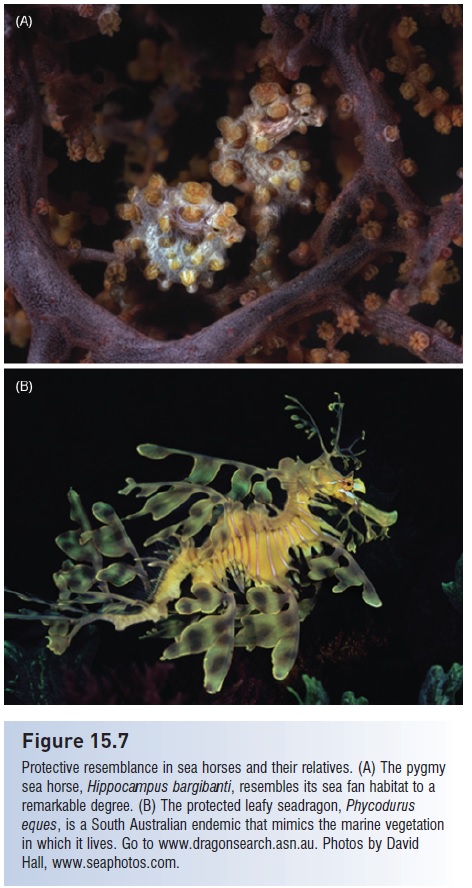

The suborder Syngnathoidei includes several unusually shaped fishes encased in bony rings, including pegasid seamoths and syngnathid pipefishes, sea dragons, and seahorses(Figs 15.6B, 15.7). In the primitive solenostomidghost pipefishes, the female carries developing eggs in abrood pouch formed by pelvic fins fused to the ventral body surface. In more advanced groups, sexual role reversal is the norm, and syngnathid pipefishes and seahorses are the only vertebrates in which the male literally becomes pregnant.An evolutionary gradient of degrees of male parentalcare exist within the family and correspond to the recognized phylogeny of the group. Pipe fish taxonomy is based in part on whether eggs are embeddedor attached to the male’s ventrum, whether the pouch is sealed or open, and whether plates or membranes protect the eggs. In primitive

Figure 15.7

Protective resemblance in sea horses and their relatives. (A) The pygmysea horse, Hippocampus bargibanti, resembles its sea fan habitat to aremarkable degree. (B) The protected leafy seadragon, Phycoduruseques, is a South Australian endemic that mimics the marine vegetationin which it lives. Go to www.dragonsearch.asn.au.

species, eggs are attached externally to the male’s ventral surface where they develop and hatch. In more advanced species, the eggs are deposited within a pouch, fertilized,and the embryos develop within the pouch, where they obtain protection, oxygenation, osmoregulation, and nutrition from the male. Such role reversal in reproductive behavior includes females that actively court and compete for males (e.g., Rosenqvist 1990). Locomotion is accomplished by rapid undulation of the small dorsal fin; the caudal fin is lacking in seahorses, which have transformed the caudal peduncle region into a prehensile structure for holding onto structures. Because of their attractiveness and small size, seahorses are actively pursued for the aquarium trade but their feeding and water quality requirements are such that few survive for long in glass boxes. Of greater

threat is unregulated and unsustainable harvest for traditional Asian medicinal preparations (Vincent 1996). Because they mate for life and reproduce slowly, seahorses are particularly vulnerable to over collecting. Fifty-one species have some international protection, with 39 listed inAppendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES; www.cites.org) and 16 consideredat risk by the IUCN .

Also exceptional within the gasterosteiforms are theaulostomoid trumpet fishes and cornet fishes, which are elongate, large (up to 1 m), lurking and stalking piscivoreswith very expandable mouths. The intriguing centriscidshrimpfishes of the Indo-Pacific are small, extremely compressed fishes with the shape and proportions of an ediblepeapod encased in thin bone (see Fig. 15.6C). Due to anal most right-angle fl exure in the vertebral column, their second dorsal, caudal, and anal fins all point ventrally and they tend to swim with their dorsal edge leading whileoriented head down. The fish typically hover head down among the spines of long-spined sea urchins where they are protected and difficult to see due to their thinness and along black lateral stripe.

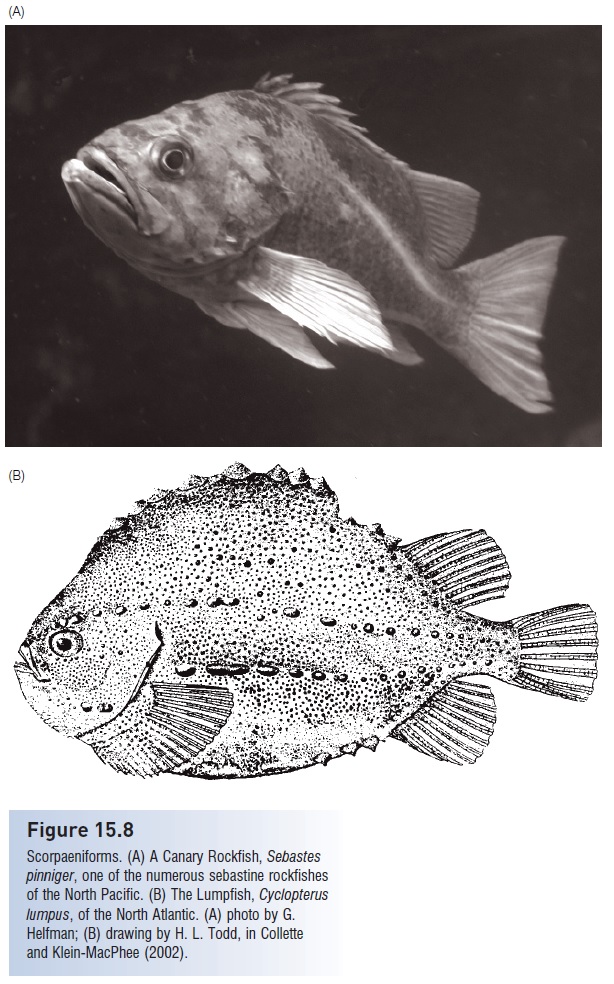

The synbranchiforms are a small order of primarily freshwater, eel-like fishes. The synbranchid swamp and riceeels are air-breathing fishes in Africa, Asia, and Central andSouth America. They have many unusual derivations,including loss of pectoral, pelvic, dorsal, anal, and, in some,caudal fins; most are protogynous (female first) hermaphrodites. Synbranchids also have a unique upper jaw arrangementin which the palatoquadrate attaches at two points to the skull, termed amphystilic suspension and not known inany other teleosts. Swamp and rice eels released by irresponsible aquarium keepers constitute a growing threat as aninvasive species in south Florida, Georgia, and Hawaii .The scorpaeniforms are a large order of predominantlymarine fishes (Fig. 15.8); their exact position within thepercomorphs is a matter of considerable debate. Most have

Figure 15.8

Scorpaeniforms. (A) A Canary Rockfish, Sebastespinniger, one of the numerous sebastine rockfishesof the North Pacific. (B) The Lumpfish,Cyclopteruslumpus, of the North Atlantic. (A) photo by G.Helfman; (B) drawing by H. L. Todd, in Colletteand Klein-MacPhee (2002).

spines projecting from different bones on the head, including a posteriorly directed spine derived from a bone below the eye, giving them the name “mail-cheeked fishes”. Manyscorpaeniforms lack scales, but this may be more part of a general suite of adaptations to benthic living than a phylogenetictrait. The dactylopterid flying gurnards have hugepectoral fins which they expand as they walk along the bottom on their elongate pelvic fins; it is unlikely that adult“flying” gurnards ever leap out of the water or for that matter ever swim far above the bottom. The scorpaenidscorpionfishes and rockfishes are a diverse group of benthicmarine fishes with large mouths and venomous spines in their dorsal, anal, and pelvic fins. The sebastinerock fishes are a diverse (133 species), important commercial group of often live-bearing, long-lived (up to >140 years), overexploited species of the temperate North Pacific (e.g., Boehlert& Yamada 1991; Love et al. 2002). Other subfamilies within this group include the colorful and venomous lionor turkey fishes (e.g., Pterois), as well as the camouflaged and highly venomous stonefishes (Synanceia) – the latter purported to possess the most deadly of fish venoms in their spines. The hexagrammid greenlings are littoral zone andkelp associated fishes endemic to the North Pacific. The family includes the highly edible, predatory, and significantly overfished Lingcod, Ophiodon elongatus.

The only freshwater scorpaeniforms are in the suborder Cottoidei, which includes the cottid sculpins of North American headwater streams and tidepools, as well as aspecies flock of comephorid oilfishes and other cottoid species in Lake Baikal in Asia. Many cottoidslack scales but have prickly skin. The Cabezon, Scorpaenichthysmarmoratus, of the Pacific coast of North Americais apparently unique among non-tetraodontiform teleostsin having toxic eggs. The most advanced scorpaeniformsare the cyclopteroid lumpfishes and snailfishes. The globoselumpfishes have bony tubercles arranged in rows around their body and a sucking disk made from modified pelvicfins, an unusual trait for fishes that do not frequent highenergyzones. The Lumpfish of the North Atlantic,Cyclopteruslumpus, is highly prized for its caviar and has been seriously depleted in parts of its range. Liparid snailfishes,which also have pelvic suction disks, occur broadly geographically and ecologically. They are found in most oceansfrom the Arctic to the Antarctic and can inhabit tidepoolsor benthic regions deeper than 7000 m.

Related Topics