Chapter: Security in Computing : Program Security

Peer Reviews

Peer Reviews

We turn next to the process of developing

software. Certain practices and techniques can assist us in finding real and

potential security flaws (as well as other faults) and fixing them before we

turn the system over to the users. Pfleeger et al. recommend several key techniques for building what they call "solid

software":

·

peer reviews

·

hazard analysis

·

testing

·

good design

·

prediction

·

static analysis

·

configuration management

·

analysis of mistakes

Here, we look at each

practice briefly, and we describe its relevance to security controls. We begin

with peer reviews.

You have probably been doing

some form of review for as many years as you have been writing code:

desk-checking your work or asking a colleague to look over a routine to ferret

out any problems. Today, a software review is associated with several formal

process steps to make it more effective, and we review any artifact of the

development process, not just code. But the essence of a review remains the

same: sharing a product with colleagues able to comment about its correctness.

There are careful distinctions among three types of peer reviews:

Review: The artifact is presented informally to a team of reviewers; the

goal is consensus and buy-in before development proceeds further.

Walk-through: The artifact is presented to the team by its creator, who leads and

controls the discussion. Here, education is the goal, and the focus is on learning about a single document.

Inspection: This more formal process is a detailed analysis in which the

artifact is checked against a prepared list of concerns. The creator does not lead the discussion,

and the fault identification and correction are often controlled by statistical

measurements.

A wise engineer who finds a

fault can deal with it in at least three ways:

·

by learning how, when, and why errors occur

·

by taking action to prevent mistakes

·

by scrutinizing products to find the instances and effects of errors

that were missed

Peer reviews address this

problem directly. Unfortunately, many organizations give only lip service to

peer review, and reviews are still not part of mainstream software engineering

activities.

But there are compelling

reasons to do reviews. An overwhelming amount of evidence suggests that various

types of peer review in software engineering can be extraordinarily effective.

For example, early studies at Hewlett-Packard in the 1980s revealed that those

developers performing peer review on their projects enjoyed a significant

advantage over those relying only on traditional dynamic testing techniques,

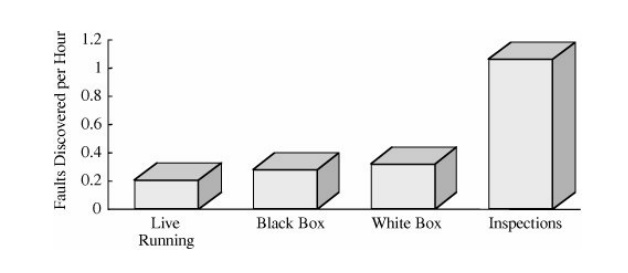

whether black box or white box. Figure 3 -19

compares the fault discovery rate (that is, faults discovered per hour) among

white-box testing, black-box testing, inspections, and software execution. It

is clear that inspections discovered far more faults in the same period of time

than other alternatives. This result is particularly compelling for large,

secure systems, where live running for fault discovery may not be an option.

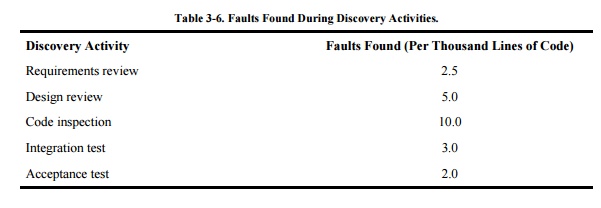

Researchers and practitioners have repeatedly

shown the effectiveness of reviews. For instance, Jones summarized the data in his large

repository of project information to paint a picture of how reviews and

inspections find faults relative to other discovery activities. Because

products vary so wildly by size, Table 3-6

presents the fault discovery rates relative to the number of thousands of lines

of code in the delivered product.

The inspection process involves several

important steps: planning, individual preparation, a logging meeting, rework,

and reinspection. Details about how to perform reviews and inspections can be

found in software engineering books such as [PFL01]

and [PFL06a].

During the review process,

someone should keep careful track of what each reviewer discovers and how

quickly he or she discovers it. This log suggests not only whether particular

reviewers need training but also whether certain kinds of faults are harder to

find than others. Additionally, a root cause analysis for each fault found may

reveal that the fault could have been discovered earlier in the process. For

example, a requirements fault that surfaces during a code review should

probably have been found during a requirements review. If there are no

requirements reviews, you can start performing them. If there are requirements

reviews, you can examine why this fault was missed and then improve the

requirements review process.

The fault log can also be

used to build a checklist of items to be sought in future reviews. The review

team can use the checklist as a basis for questioning what can go wrong and

where. In particular, the checklist can remind the team of security breaches,

such as unchecked buffer overflows, that should be caught and fixed before the

system is placed in the field. A rigorous design or code review can locate

trapdoors, Trojan horses, salami attacks, worms, viruses, and other program

flaws. A crafty programmer can conceal some of these flaws, but the chance of

discovery rises when competent programmers review the design and code,

especially when the components are small and encapsulated. Management should

use demanding reviews throughout development to ensure the ultimate security of

the programs.

Related Topics