Chapter: Security in Computing : Program Security

How Viruses Attach

How Viruses Attach

A printed copy of a virus does nothing and

threatens no one. Even executable virus code sitting on a disk does nothing.

What triggers a virus to start replicating? For a virus to do its malicious

work and spread itself, it must be activated by being executed. Fortunately for

virus writers but unfortunately for the rest of us, there are many ways to

ensure that programs will be executed on a running computer.

For example, recall the SETUP

program that you initiate on your computer. It may call dozens or hundreds of

other programs, some on the distribution medium, some already residing on the

computer, some in memory. If any one of these programs contains a virus, the

virus code could be activated. Let us see how. Suppose the virus code were in a

program on the distribution medium, such as a CD; when executed, the virus

could install itself on a permanent storage medium (typically, a hard disk) and

also in any and all executing programs in memory. Human intervention is

necessary to start the process; a human being puts the virus on the

distribution medium, and perhaps another initiates the execution of the program

to which the virus is attached. (It is possible for execution to occur without

human intervention, though, such as when execution is triggered by a date or

the passage of a certain amount of time.) After that, no human intervention is

needed; the virus can spread by itself.

A more common means of virus

activation is as an attachment to an e-mail message. In this attack, the virus

writer tries to convince the victim (the recipient of the e-mail message) to

open the attachment. Once the viral attachment is opened, the activated virus

can do its work. Some modern e-mail handlers, in a drive to "help"

the receiver (victim), automatically open attachments as soon as the receiver

opens the body of the e-mail message. The virus can be executable code embedded

in an executable attachment, but other types of files are equally dangerous.

For example, objects such as graphics or photo images can contain code to be

executed by an editor, so they can be transmission agents for viruses. In

general, it is safer to force users to open files on their own rather than

automatically; it is a bad idea for programs to perform potentially

security-relevant actions without a user's consent. However, ease-of-use often

trumps security, so programs such as browsers, e-mail handlers, and viewers

often "helpfully" open files without asking the user first.

Appended Viruses

A program virus attaches

itself to a program; then, whenever the program is run, the virus is activated.

This kind of attachment is usually easy to program.

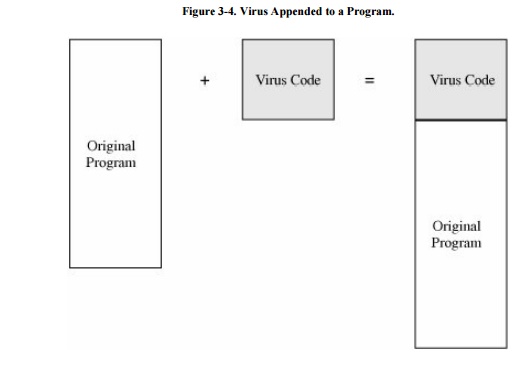

In the simplest case, a virus inserts a copy of

itself into the executable program file before the first executable

instruction. Then, all the virus instructions execute first; after the last

virus instruction, control flows naturally to what used to be the first program

instruction. Such a situation is shown in Figure

3-4.

This kind of attachment is

simple and usually effective. The virus writer does not need to know anything

about the program to which the virus will attach, and often the attached

program simply serves as a carrier for the virus. The virus performs its task

and then transfers to the original program. Typically, the user is unaware of

the effect of the virus if the original program still does all that it used to.

Most viruses attach in this manner.

Viruses That Surround a Program

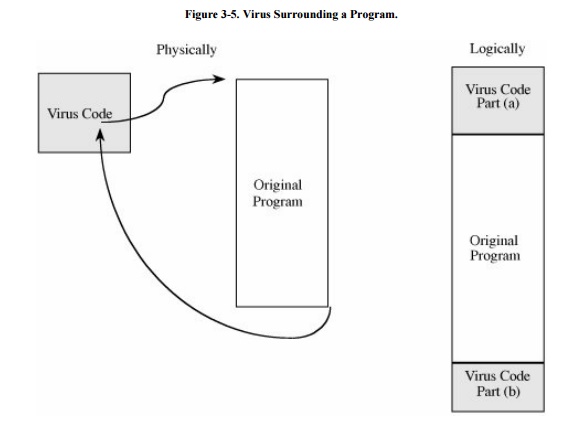

An alternative to the attachment is a virus

that runs the original program but has control before and after its execution.

For example, a virus writer might want to prevent the virus from being

detected. If the virus is stored on disk, its presence will be given away by

its file name, or its size will affect the amount of space used on the disk.

The virus writer might arrange for the virus to attach itself to the program

that constructs the listing of files on the disk. If the virus regains control

after the listing program has generated the listing but before the listing is

displayed or printed, the virus could eliminate its entry from the listing and

falsify space counts so that it appears not to exist. A surrounding virus is

shown in Figure 3-5.

Integrated Viruses and Replacements

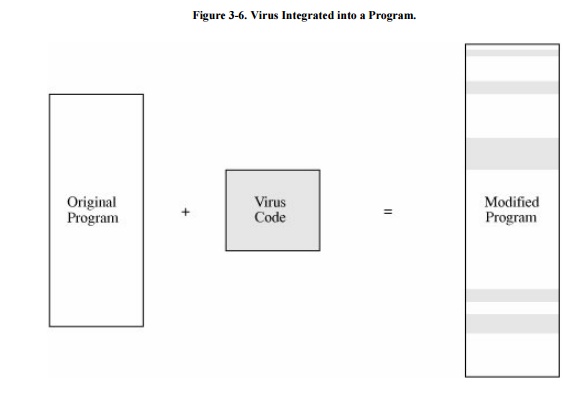

A third situation occurs when the virus

replaces some of its target, integrating itself into the original code of the

target. Such a situation is shown in Figure 3-6.

Clearly, the virus writer has to know the exact structure of the original

program to know where to insert which pieces of the virus.

Finally, the virus can replace

the entire target, either mimicking the effect of the target or ignoring the

expected effect of the target and performing only the virus effect. In this

case, the user is most likely to perceive the loss of the original program.

Document Viruses

Currently, the most popular

virus type is what we call the document

virus, which is implemented within a formatted document, such as a written

document, a database, a slide presentation, a picture, or a spreadsheet. These

documents are highly structured files that contain both data (words or numbers)

and commands (such as formulas, formatting controls, links). The commands are

part of a rich programming language, including macros, variables and

procedures, file accesses, and even system calls. The writer of a document

virus uses any of the features of the programming language to perform malicious

actions.

The ordinary user usually

sees only the content of the document (its text or data), so the virus writer

simply includes the virus in the commands part of the document, as in the

integrated program virus.

Related Topics