Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abnormal Labor and Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance

Operative Delivery

OPERATIVE DELIVERY

Operative vaginal deliveries are

accomplished by apply-ing direct traction on the fetal skull with forceps, or

by applying traction to the fetal scalp by means of a vacuum extractor. The

incidence of operative vaginal delivery in the United States is estimated to be

10% to 15%. Although considered safe in

appropriate circumstances, opera-tive vaginal delivery has the potential for

maternal and neo-natal complications. Operative vaginal delivery shouldbe

performed only by individuals with privileges for such procedures and in

settings in which personnel are read-ily available to perform a cesarean

delivery in the event the operative vaginal delivery is unsuccessful. However,

the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage is highest among infants delivered by

cesarean section following a failed vacuum or forceps delivery. The combination

of vacuum and forceps has a similar risk for intracranial hemor-rhage.

Therefore, an operative vaginal delivery should not be attempted when the

probability of success is very low

Classification

For both forceps and vacuum

extraction deliveries, the type of delivery depends on the fetal station—the

relationship between the leading portion of the fetal head and the level of the

maternal ischial spines. Outlet

operative vaginaldelivery is the application of forceps or vacuum under

thefollowing conditions:

·

The scalp is visible at the

introitus without separating labia.

·

The fetal skull has reached

pelvic floor.

·

The sagittal suture is in

anteroposterior diameter or right or left occiput anterior or posterior

position.

·

The fetal head is at or on the

perineum.

·

Rotation does not exceed 45°.

Low

operative vaginal delivery is the application offorceps or

vacuum when the leading point of the fetal skull is at station +2 or more and is not on the

pelvic floor. This type of operative vaginal delivery has two sub-types:

·

Rotation 45° or less (left or right occiput

anterior to occiput anterior, or left or right occiput posterior to occiput

posterior)

·

Rotation greater than 45°

Midpelvis

operative vaginal delivery is the applicationof forceps or

vacuum when the fetal head is engaged but the leading point of the skull is

above station +2. Under

very unusual circumstances, such as the sudden onset of severe fetal or

maternal compromise, application of for-ceps or vacuum above station +2 may be attempted while

simultaneously initiating preparation for a cesarean de-livery in the event

that the operative vaginal delivery is unsuccessful.

Indications and Contraindications

No indication for operative

vaginal delivery is absolute. The following indications apply when the fetal

head is engaged and the cervix is fully dilated:

· Prolonged

or arrested second stage of labor

· Suspicion

of immediate or potential fetal compromise

· Shortening

of the second stage for maternal benefit

In certain situations, operative

vaginal delivery should be avoided or, at the least, carefully considered in

terms of rel-ative maternal and fetal risks. Most authorities consider vac-uum

extraction inappropriate in pregnancies before 34 weeks of gestation because of

the risk of fetal intraventricular hemorrhage. Operative delivery also is contraindicated if alive fetus is known to

have a bone demineralization condition (e.g., osteogenesis imperfecta) or has a

bleeding disorder (e.g., allo-immune thrombocytopenia, hemophilia, or von

Willebrand dis-ease), and if the fetal head is unengaged or the position of the

fetal head is unknown

Forceps

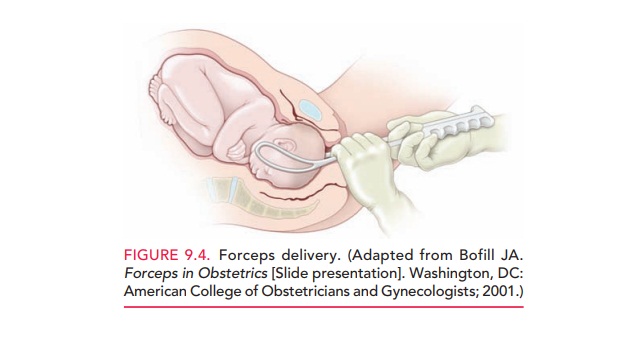

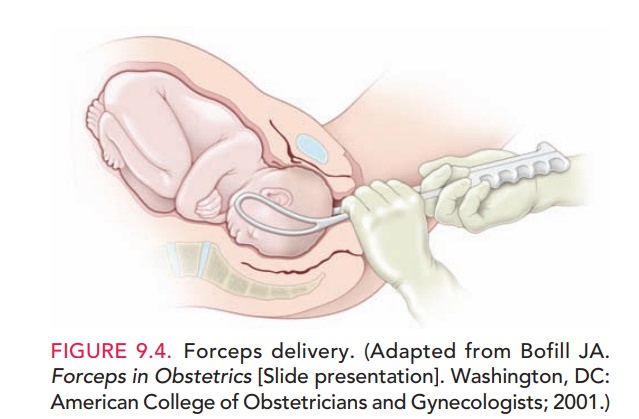

Forceps are

primarily used to apply traction to the fetalhead to augment the expulsive

forces, when the mother’s voluntary efforts in conjunction with uterine

contractions are insufficient to deliver the infant (Fig. 9.4). Occasionally,

forceps are used to rotate the fetal head before applying traction to complete

vaginal delivery. Forceps also may be used to control delivery of the fetal

head, thereby avoiding precipitous delivery. Different types of forceps are

available for the different degrees of molding of the fetal head.

Maternal complications of forceps

delivery include per-ineal trauma, hematoma, and pelvic floor injury. Neonatal

risks include injuries to the brain and spine, musculoskeletal injury, and

corneal abrasion if the forceps are mistakenly ap-plied over the neonate’s

eyes. The risk of shoulder dysto-cia, in

which the fetus’s anterior shoulder becomes lodgedagainst the pubic symphysis,

is increased in forceps deliver-ies of infants weighing over 4000 g.

Vacuum Extraction

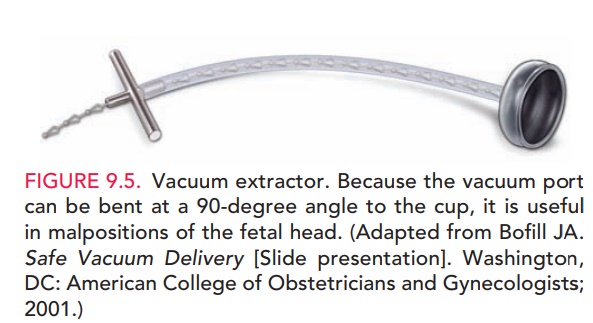

In vacuum extraction, a soft vacuum cup is applied to the fetal head

and suction is exerted by means of a mechanical pump (Fig. 9.5). Vacuum

extraction is associated with less maternal trauma than are forceps, but carries

significant neonatal risks. Although the amount of traction applied to the

fetal skull is less than that applied with forceps, it is still substantial and

can cause serious fetal injury. Neonatal risks include intracranial hemorrhage,

subgaleal hematomas, scalp lacerations (if torsion is excessive),

hyperbiliru-binemia, and retinal hemorrhage. In addition, separation of the

scalp from the underlying structures can lead to cephalohematoma. Overall, the incidence of serious

complica-tions with vacuum extraction is approximately 5%. It is

rec-ommended that rocking movements or torque not be applied to the device and

that only steady traction in the

Clinicians caring for the neonate should also be alerted that an

operative deliv-ery has been used so that they can monitor the neonate for

signs and symptoms of injury.

Related Topics