Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Abnormal Labor and Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance

Abnormal Labor

ABNORMAL LABOR

Abnormal

labor, or labor

dystocia (literally, “difficultlabor or childbirth”) is characterized by

the abnormal pro-gression of labor. Dystocia is the leading indication for

primary cesarean delivery in the United States. Despite thehigh prevalence of labor disorders, considerable variability

exists in the diagnosis, management, and criteria for dystocia that re-quires

intervention. Because dystocia can rarely be diag-nosed with certainty, the

relatively imprecise term “failure to progress” has been used, which includes

lack of pro-gressive cervical dilation or lack of descent of the fetal head or

both.

Factors That Contribute to Normal Labor— The Three Ps

Labor is the

occurrence of uterine contractions of suffi-cient intensity, frequency, and

duration to bring about demonstrable effacement and dilation of the cervix. Dystocia

results from what have been categorized classi-cally as abnormalities of the

“power” (uterine contractions or maternal expulsive forces), “passenger”

(position, size, or presentation of the fetus), or “passage” (pelvis or soft

tissues).

UTERINE CONTRACTIONS (“POWER”)

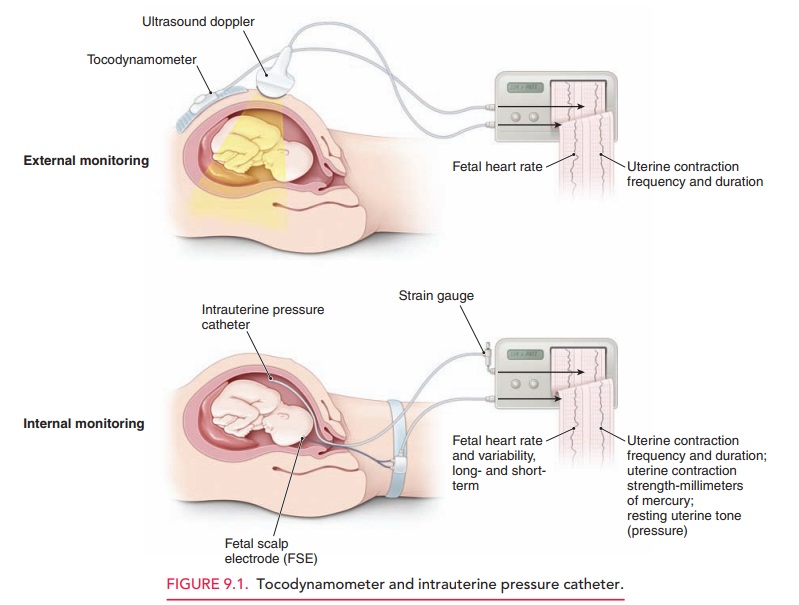

Uterine

activity can be monitored by palpation, external tocody-namometry, or by using

intrauterine pressure catheters (IUPCs) (Fig.

9.1). A tocodynamometer is an external strain gauge that is placed on the

maternal abdomen. It records the frequency of uterine contractions and

relaxations, as well as the duration of each contraction. An IUPC, in ad-dition

to recording contraction frequency and duration, also directly measures the

pressure generated by uterine contractions, via a catheter inserted into the

uterine cav-ity. The catheter is attached to a gauge that measures

intra-uterine pressure in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg).

Recent

studies suggest that the use of an IUPC instead of external tocodynamometry

does not affect the outcome in cases of abnormal labor.

However, an IUPC may be useful in

specific situations, such as maternal obesity or other factors that may prevent

accurate clinical evaluation of uterine contractions.

For cervical dilation and fetal

descent to occur, each uterine contraction must generate at least 25 mm Hg of

peak pressure. Optimal intrauterine pressure is 50 to 60 mm Hg. The frequency

of uterine contractions is also impor-tant in generating a normal labor

pattern: the optimal fre-quency of uterine contractions is a minimum of three

contractions in a 10-minute interval, often described as “adequate.” Uterine

contractions that are too frequent are not optimal, because they prevent

intervals of uterine re-laxation. During this “rest interval,” the fetus receives

unimpeded uteroplacental blood flow for oxygen and waste transport. Without

these rest periods, fetal oxygenation may be compromised.

Another unit of measure commonly

used to assess con-tractile strength is the Montevideo unit (MVU). This unit is the number of uterine

contractions in 10 minutes times the average intensity (above the resting

baseline intrauterine pressure). Normal

progress of labor is usually associated with 200or more Montevideo units.

FETAL FACTORS (“PASSENGER”)

Evaluation of the passenger

includes clinical estimation of fetal weight and clinical evaluation of fetal

lie, presenta-tion, position, and attitude. If

a fetus has an estimated weightgreater than 4000 to 4500 grams, the risk of

dystocia, includ-ing shoulder dystocia and fetopelvic disproportion, is

greater. Because ultrasound estimation of fetal weight is often in-accurate

by as much as 500 to 1000 grams when the fetus is near term (40 weeks’

gestational age), this information must be used in conjunction with other

parameters when making management decisions.

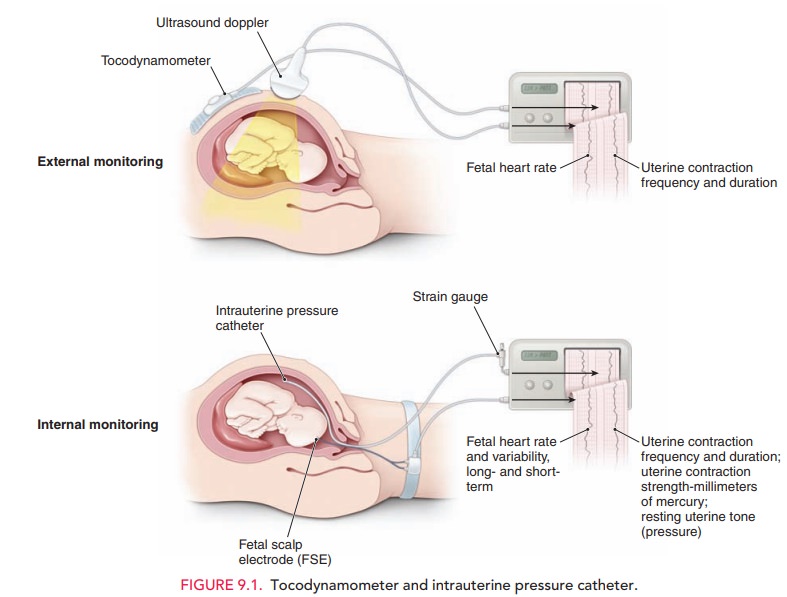

Fetal

attitude, presentation, and lie also play a role in the progress of labor (Fig.

9.2). If the fetal head is asynclitic (turnedto one side; asynclitism) or extended (extension),

a larger cephalic diameter is presented to the pelvis, thereby increas-ing the

possibility of dystocia. A brow

presentation (about 1 in 3000 deliveries) typically converts to either a

vertex or face presentation, but, if persistent, may cause dystocia re-quiring

cesarean delivery. Likewise, a face

presentation (about 1 in 600 to 1000 deliveries) requires cesarean

deliv-ery in most cases. However, a mentum

anterior presenta-tion (chin toward mother’s abdomen) may be

deliveredvaginally if the fetal head undergoes flexion, rather than the normal

extension. A persistentoccipitoposterior positionis

alsoassociated with longer labors (approximately 1 hour in multiparous patients

and 2 hours in nulliparous patients). Incompoundpresentations, when one or more limbs prolapse alongsidethe

presenting part (about 1 in 700 deliveries), the extrem-ity usually retracts

(either spontaneously or with manual as-sistance) as labor continues. When it

does not, or in the 15% to 20% of compound presentations associated with

umbilical cord prolapse, cesarean delivery is required.

Fetal anomalies, such as

hydrocephaly and soft tissue tumors, may also cause dystocia. The routine use

of prena-tal ultrasound for other causes has allowed identification of these

situations, significantly reducing the incidence of un-expected dystocia of

this kind.

MATERNAL FACTORS (“PASSAGE”)

A number of maternal factors are

associated with dystocia. Dystocia can result from maternal skeletal or

soft-tissue anomalies that obstruct the birth canal. Cephalopelvicdisproportion, in which the size of the maternal

pelvis isinadequate to the size of the presenting part of the fetus, may impede

fetal descent into the birth canal.

Clinical,

radiographic, and CT measurements of the bony pelvis are poor predictors of

successful vaginal delivery, due to the inaccuracy of these measurements as

well as case-by-case differences in fetal accommodation and mechanisms of

labor.

Clinical

pelvimetry, the manual evaluation of the diam-eters of the

pelvis, is also a poor predictor of successful vaginal birth, except in rare

circumstances when the pelvic diameters are so small as to render the pelvis

“completely contracted.” Although radiographic and CT pelvimetry can be helpful

in some cases, the progress of descent of the presenting part in labor is the

best test of pelvic adequacy.

Soft-tissue causes of dystocia

include abnormalities of the cervix, tumors or other lesions of the colon or

adnexa, distended bladder, uterine fibroids, an accessory uterine horn, and

morbid obesity. Epidural anesthesia may con-tribute to dystocia by decreasing

the tone of the pelvic floor musculature.

Risks

Dystocia

may be associated with serious complications for both the woman and the fetus. Infection

(chorioamnionitis) is aconsequence of prolonged labor, especially in the

setting of ruptured membranes. Fetal infection and bacteremia, including

pneumonia caused by aspiration of infected amniotic fluid, is linked to

prolonged labor. In addition, there are the attendant risks of cesarean or

operative de-livery, such as maternal soft tissue injury to the lower genital

tract and fetal trauma

Diagnosis and Management of Abnormal Labor Patterns

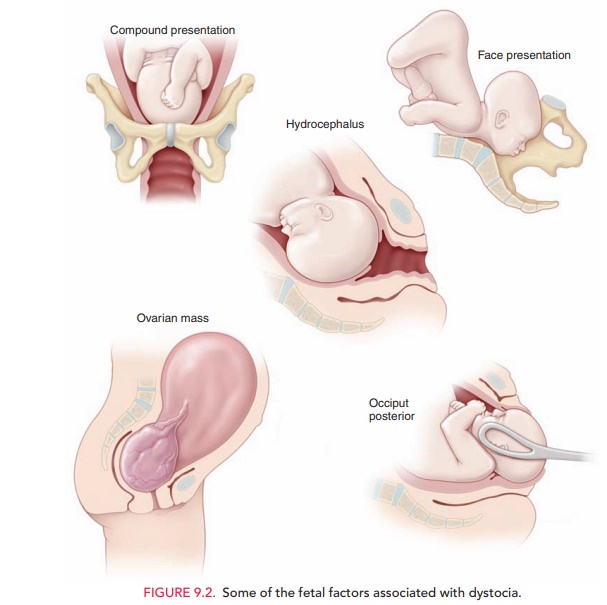

Graphic documentation of

progressive cervical dilation and effacement facilitates assessing a patient’s

progress in labor and identifying abnormal labor patterns. The Friedman Curve

is commonly used for this purpose. Labor abnormalities can be categorized into

two general types: protraction disorders,

in which labor is slow to progress, and arrest

disorders, in which labor ceases to progress (Table 9.1). Protraction can

occur dur-ing both the latent and active phases of labor, while arrest is

recognized only in the active phase. Although the defi-nition of the latent phase of labor is controversial,

in gen-eral it can be defined as the phase in which the cervix effaces but

undergoes minimal dilation.

Management of abnormal labor

encompasses a wide range of options, from observation to operative or cesarean

delivery. Management choice depends on several factors:

·

Adequacy of uterine contractions

·

Fetal malposition or

cephalopelvic disproportion

·

Other clinical conditions, such

as nonreassuring fetal status or chorioamnionitis

Management decisions should be

balanced between ensur-ing a positive outcome for mother and fetus and avoiding

the concomitant risks of operative and cesarean delivery.

FIRST-STAGE DISORDERS

prolonged latent phase is one that exceeds 20 hours in

anulliparous patient or 14 hours in a multiparous patient. A pro-longed latent

phase does not necessarily predict an abnormal ac-tive phase of labor. Some

patients who have initially beendiagnosed as having a prolonged latent phase

are subse-quently found to have been in false labor. A prolonged la-tent phase

does not in itself pose a danger to the mother or fetus. Options for management

of women with a pro-longed latent phase of labor include observation and

seda-tion. With either of these options, the patient may stop having contractions,

in which case she is not in labor; may go into active labor; or may continue

experiencing pro-longed labor into the active phase. In the latter case, other

interventions as described below may be administered to augment uterine

contractions.

Once the patient is in active labor, the first stage is consid-ered prolonged when the cervix dilates less than 1 cm per hour in nulliparous women, and less than 1.2 to 1.5 cm per hour in multi-parous women. Management options for a prolonged firststage include observation, augmentation by amniotomy or oxytocin, and continuous support. Cesarean delivery usu-ally is warranted if maternal or fetal status becomes non-reassuring.

Augmentation Augmentationrefers to stimulation ofuterine contractions when spontaneous

contractions have failed to result in progressive cervical dilation or de-scent

of the fetus. Augmentation can be achieved with amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes) or oxy-tocin

administration. Augmentation should be

consideredif the frequency of contractions is less than 3 contractions per 10

minutes or the intensity of contractions is less than 25 mm Hg above the

baseline or both. Before augmentation, the mater-nal pelvis and cervix as

well as fetal position, station, and well-being should be assessed. If there is

no evidence of disproportion, oxytocin can be used if uterine contractions are

judged to be inadequate. Contraindications to aug-mentation are similar to

those for labor induction .

If the

membranes have not ruptured, amniotomy may en-hance progress in the active

phase and negate the need for oxytocin augmentation. Amniotomy

allows the fetal head, rather thanthe otherwise intact amniotic sac, to be the

dilating force. It may also stimulate the release of prostaglandins, which

could aid in augmenting the force of contractions.

Amniotomy is usually performed with a thin, plastic rod with a sharp hook on the end. The end is guided to the open cervical os with the examiner’s fingers, and the hook is used to snag and disrupt the amniotic sac. Risks of amniotomy include fetal heart rate decelerations due to cord compression and an increased incidence of chorioamnionitis. For these reasons, amniotomy should not be routine and should be used for women with pro-longed labor. The fetal heart rate (FHR) should be eval-uated both before and immediately after rupture of the membranes.

It has

been shown that amniotomy combined with oxytocin administration early in the

active stage reduces labor by up to 2 hours, although there is no change in the

rate of cesarean delivery with this treatment protocol.

The goal of oxytocin

administration is to effect uterine ac-tivity sufficient to produce cervical

change and fetal de-scent while avoiding uterine hyperstimulation and fetal

compromise. Typically, a goal of a maximum of 5 contrac-tions in a 10-minute

period with resultant cervical dilation is considered adequate. Oxytocin may be

administered in low-dose or high-dose regimens. Low-dose regimens are associated

with a decreased incidence and severity of uterine hyperstimulation. High-dose

regimens are associated with decreased labor times, incidence of

chorioamnionitis, and cesarean delivery for dystocia.

Continuous Labor

Support Continuous support duringlabor from

caregivers (nurses, midwives, or lay individuals) may have a number of benefits

for women and their new-borns. Continuous care has been associated with reduced need for

pain relief and oxytocin administration, lower rates of cesarean and operative

deliveries, decreased incidence of 5-minute Apgar scores lower than 7, and

increased patient satisfaction with the labor experience. However, there are

insufficient data comparing differences in benefits on the basis of level of

training of support personnel—that is, whether the caregivers were nurses,

midwives, or doulas. There is no evidence of harmful effects from continuous

support during labor.

SECOND-STAGE DISORDERS

A

second-stage protraction disorder should be considered when the second stage

exceeds 3 hours if regional anesthesia has been ad-ministered, or 2 hours if no

regional anesthesia is used, or if the fetus descends at a rate of less than 1

cm per hour if no regional anesthesia is used. Second-stage arrest is diagnosed

when there is no descent after 1 hour of pushing. In the

past, the fetus wasthought to be at increased risk for morbidity and mortality

when the second stage exceeded 2 hours. Currently, more intensive intrapartum

surveillance provides the ability to identify the fetus that may not be

tolerating labor well.

Thus, the

length of the second stage of labor is not in itself an absolute or even a

strong indication for operative or cesarean delivery.

As long as heart tones continue

to be reassuring and cephalopelvic disproportion has been ruled out, it is

con-sidered safe to allow the second stage to continue. If uterine contractions

are inadequate, oxytocin adminis-tration can be initiated or the dosage

increased if already in place.

Bearing down efforts by the

patient in conjunction with uterine contractions help bring about delivery.

Labor positions other than the dorsal lithotomy position (e.g., knee-chest,

sitting, squatting, or birth-chair) may bring about subtle changes in fetal

presentation and facilitate vaginal delivery. Fetal accommodation may also be

facili-tated by allowing the effects of epidural analgesia to dissi-pate. The

absence of epidural analgesia may increase the tone of the pelvic floor

muscles, facilitating the cardinal movements of labor and restoring the urge to

push. In some cases of fetal malpresentation, manual techniques can facilitate

delivery. If the fetus is in the occipitoposte-rior position and does not

spontaneously convert to the nor-mal position, rotation can be performed to

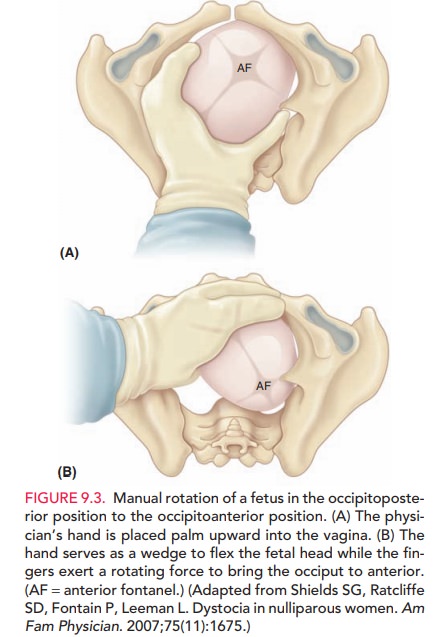

turn the fetus to the anterior position (Fig. 9.3).

The decision to perform an operative delivery in the second stage versus continued observation should be made on the basis of clinical assessment of the woman and the fetus and the skill and training of the obstetrician. Nonreassuring status of the fetus or mother is an indica-tion for operative or cesarean delivery.

Related Topics