Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Oncology: Nursing Management in Cancer Care

Nursing Process: The Patient With Cancer

NURSING

PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH CANCER

The outlook for patients with cancer has greatly improved be-cause of

scientific and technological advances. As a result of the underlying disease or

various treatment modalities, however, the patient with cancer may experience a

variety of secondary prob-lems, such as infection, reduced WBC counts,

bleeding, skin problems, nutritional problems, pain, fatigue, and psychological

stress.

Assessment

Regardless of the type of cancer treatment or prognosis, many pa-tients

with cancer are susceptible to the following problems and complications. An

important role of the nurse on the oncology team is to assess the patient for

these problems and complications.

INFECTION

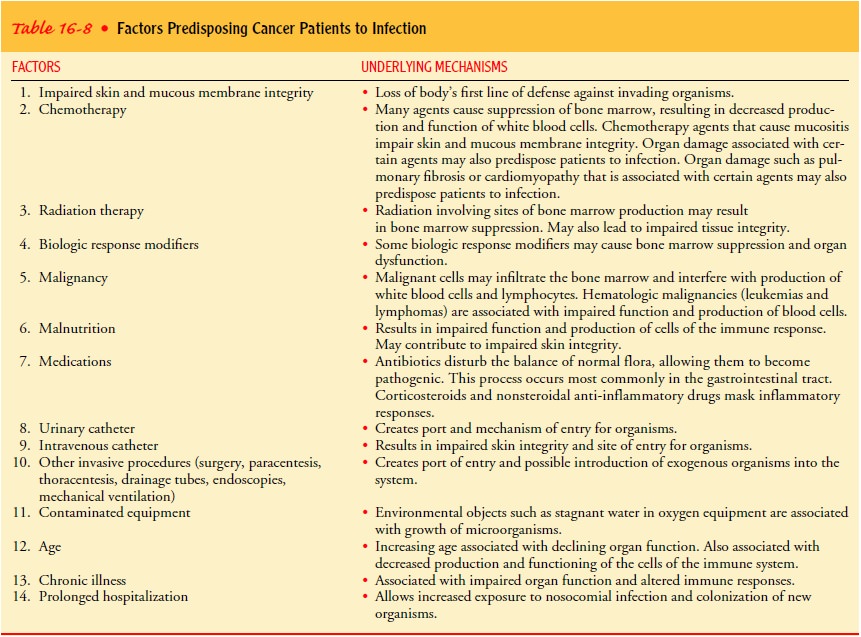

In all stages of cancer, the nurse assesses factors that can promote

infection. Infection is the leading cause of death in cancer patients. Factors

predisposing patients to infection are summarized in Table 16-8. The nurse

monitors laboratory studies to detect early changes in WBC counts. Common sites

of infection, such as the pharynx, skin, perianal area, urinary tract, and

respiratory tract, are assessed frequently. The typical signs of infection

(swelling, redness, drainage, and pain), however, may not occur in the

im-munosuppressed patient due to a diminished local inflammatory response.

Fever may be the only sign of infection that the patient exhibits. The nurse

also monitors the patient for sepsis, particu-larly if invasive catheters or

infusion lines are in place.

WBC function is often impaired in cancer patients. A decrease in

circulating WBCs is referred to as leukopenia or granulocytope-nia. There are

three types of WBCs: neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils. The neutrophils,

totaling 60% to 70% of all the body’s WBCs, play a major role in combating

infection by engulfing and destroying infective agents in a process called

phagocytosis. Both the total WBC count and the concentration of neutrophils are

im-portant in determining the patient’s ability to fight infection.

A differential WBC count

identifies the relative numbers of WBCs and permits tabulation of

polymorphonuclear neu-trophils (mature neutrophils, reported as “polys,” PMNs,

or “segs”) and immature forms of neutrophils (reported as bands,

metamyelocytes, and “stabs”). These numbers are compiled and reported as the

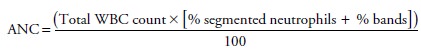

absolute neutrophil count (ANC). The ANC is calculated by the following

formula:

For example, if the

patient’s total WBC count is 6,000, with segmented neutrophils 25% and bands

25%, the ANC would be 3,000.

Neutropenia, an

abnormally low ANC, is associated with an increased risk for infection. The

risk for infection rises as the ANC decreases and persists. An ANC of less than

1,000 cells/mm3 re-flects a severe risk

for infection.Nadir is the lowest

ANC after myelosuppressive chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Therapies that

suppress bone marrow function are called myelosuppressive. Febrile patients who

are neutropenic are assessed for infection through cultures of blood, sputum,

urine, stool, catheter, or wounds, if appropriate. In addition, a chest x-ray

is often included to assess for pulmonary infections.

BLEEDING

The nurse assesses cancer patients for factors that may contribute to

bleeding. These include bone marrow suppression from radi-ation, chemotherapy,

and other medications that interfere with coagulation and platelet functioning,

such as aspirin, dipyri-damole (Persantine), heparin, or warfarin (Coumadin).

Com-mon bleeding sites include skin and mucous membranes; the intestinal,

urinary, and respiratory tracts; and the brain. Gross hem-orrhage, as well as

blood in the stools, urine, sputum, or vomitus (melena, hematuria, hemoptysis,

hematemesis), oozing at injec-tion sites, bruising (ecchymosis), petechiae, and

changes in men-tal status, are monitored and reported.

SKIN PROBLEMS

The integrity of skin and tissue is at risk in cancer patients be-cause of the effects of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, and invasive procedures carried out for diagnosis and therapy. As part of the assessment, the nurse identifies which of these pre-disposing factors are present and assesses the patient for other risk factors, including nutritional deficits, bowel and bladder incon-tinence, immobility, immunosuppression, multiple skin folds, and changes related to aging. Skin lesions or ulcerations sec-ondary to the tumor are noted. Alterations in tissue integrity throughout the gastrointestinal tract are particularly bothersome to the patient. Any lesions of the oral mucous membranes are noted, as are their effects on the patient’s nutritional status and comfort level.

HAIR LOSS

Alopecia (hair loss) is another form of tissue

disruption commonto cancer patients who receive radiation therapy or

chemother-apy. In addition to noting hair loss, the nurse also assesses the

psy-chological impact of this side effect on the patient and the family.

NUTRITIONAL CONCERNS

Assessing the patient’s nutritional status is an important nursing role.

Impaired nutritional status may contribute to disease pro-gression, immune

incompetence, increased incidence of infec-tion, delayed tissue repair,

diminished functional ability, and decreased capacity to continue

antineoplastic therapy. Altered nutritional status, weight loss, and cachexia

(muscle wasting, emaciation) may be secondary to decreased protein and caloric

intake, metabolic or mechanical effects of the cancer, systemic disease, side

effects of the treatment, or the emotional status of the patient.

The patient’s weight and caloric intake are monitored on a consistent

basis. Other information obtained through assessment includes diet history, any

episodes of anorexia, changes in appetite, situations and foods that aggravate

or relieve anorexia, and med-ication history. Difficulty in chewing or

swallowing is determined and the occurrence of nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea is

noted.

Clinical and laboratory data useful in assessing the patient’s

nutritional status include anthropometric measurements (triceps skin fold and

middle-upper arm circumference), serum protein levels (albumin and

transferrin), serum electrolytes, lymphocyte count, skin response to

intradermal injection of antigens, hemo-globin levels, hematocrit, urinary

creatinine levels, and serum iron levels.

PAIN

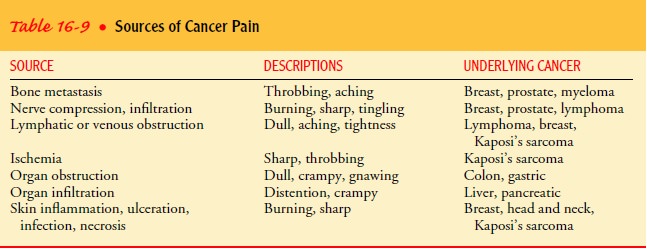

Pain and discomfort in

cancer may be related to the underlying disease, pressure exerted by the tumor,

diagnostic procedures, or the cancer treatment itself. As in any other

situation involving pain, cancer pain is affected by both physical and

psychosocial in-fluences.

In addition to assessing the source and site of pain, the nurse also

assesses those factors that increase the patient’s perception of pain, such as

fear and apprehension, fatigue, anger, and social iso-lation. Pain assessment

scales are useful in assess ing the

patient’s pain level before pain-relieving interventions are instituted and in

evaluating their effectiveness.

FATIGUE

Acute fatigue, which occurs after an energy-demanding experi-ence,

serves a protective function; chronic fatigue, however, does not. It is often

overwhelming, excessive, and not respon-sive to rest, and it seriously affects

quality of life. Fatigue is the most commonly reported side effect in patients

who receive chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The nurse assesses for

feel-ings of weariness, weakness, lack of energy, inability to carry out

necessary and valued daily functions, lack of motivation, and in-ability to

concentrate. Patients may become less verbal and ap-pear pallid, with relaxed

facial musculature. The nurse assesses physiologic and psychological stressors

that can contribute to fa-tigue, including pain, nausea, dyspnea, constipation,

fear, and anxiety. (See Nursing Research Profile 16-2.)

PSYCHOSOCIAL STATUS

Nursing assessment also

focuses on the patient’s psychological and mental status as the patient and the

family face this life-threatening experience, unpleasant diagnostic tests and

treatment modalities, and progression of disease. The patient’s mood and

emotional reaction to the results of diagnostic testing and prog-nosis are

assessed, along with evidence that the patient is pro-gressing through the

stages of grief and can talk about the diagnosis and prognosis with the family.

BODY IMAGE

Cancer patients are

forced to cope with many assaults to body image throughout the course of

disease and treatment. Entry into the health care system is often accompanied

by deperson-alization. Threats to self-concept are enormous as patients face

the realization of illness, possible disability, and death. To ac-commodate

treatments or because of the disease, many cancer patients are forced to alter

their lifestyles. Priorities and values change when body image is threatened.

Disfiguring surgery, hair loss, cachexia, skin changes, altered communication

pat-terns, and sexual dysfunction are some of the devastating results of cancer

and its treatment that threaten the patient’s self-esteem and body image. The nurse

identifies these potential threats and assesses the patient’s ability to cope

with these changes.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based on the assessment

data, nursing diagnoses of the patient with cancer may include the following:

·

Impaired oral mucous membrane

·

Impaired tissue integrity

·

Impaired tissue integrity: alopecia

·

Impaired tissue integrity: malignant skin lesions

·

Imbalanced nutrition, less than body requirements

·

Anorexia

·

Malabsorption

·

Cachexia

·

Chronic pain

·

Fatigue

·

Disturbed body image

· Anticipatory grieving

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Based on the assessment

data, potential complications that may develop include the following:

•

Infection and sepsis

•

Hemorrhage

•

Superior vena cava syndrome

•

Spinal cord compression

•

Hypercalcemia

•

Pericardial effusion

•

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

•

Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic

hor-mone

•

Tumor lysis syndrome

See the later section,

Oncologic Emergencies, for more information.

Planning and Goals

The major goals for the

patient may include management of stomatitis, maintenance of tissue integrity,

maintenance of nu-trition, relief of pain, relief of fatigue, improved body

image, effective progression through the grieving process, and absence of

complications.

Nursing Interventions

The patient with cancer

is at risk for various adverse effects of therapy and complications. The nurse

in all health care settings, including the home, assists the patient and family

in managing these problems.

MANAGING STOMATITIS

Stomatitis, an inflammatory response of the oral tissues, commonlydevelops within

5 to 14 days after the patient receives certain chemotherapeutic agents, such

as doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil, and BRMs, such as IL-2 and IFN. As many as

40% of patients receiving chemotherapy experience some degree of stomatitis

during treatment. Patients receiving dose-intensive chemother-apy (considerably

higher doses than conventional dosing), such as those undergoing BMT, are at

increased risk for stomatitis. Stomatitis may also occur with radiation to the

head and neck. Stomatitis is characterized by mild redness (erythema) and edema

or, if severe, by painful ulcerations, bleeding, and secondary in-fection. In

severe cases of stomatitis, cancer therapy may be tem-porarily halted until the

inflammation decreases.

As a result of normal

everyday wear and tear, the epithelial cells that line the oral cavity undergo

rapid turnover and slough off routinely. Chemotherapy and radiation interfere

with the body’s ability to replace those cells. An inflammatory response

develops as denuded areas appear in the oral cavity. Poor oral hygiene,

existing dental disease, use of other medications that dry mucous membranes,

and impaired nutritional status contribute to morbidity associated with

stomatitis. Radiation-induced xe-rostomia (dry mouth) associated with decreased

function of the salivary glands may contribute to stomatitis in patients who

have received radiation to the head and neck.

Myelosuppression (bone marrow depression) resulting from underlying

disease or its treatment predisposes the patient to oral bleeding and

infection. Pain associated with ulcerated oral tissues can significantly

interfere with nutritional intake, speech, and a willingness to maintain oral

hygiene.

Although multiple studies on stomatitis have been published, the optimal

prevention and treatment approaches have not been identified. However, most

clinicians agree that good oral hygiene that includes brushing, flossing, and

rinsing is necessary to minimize the risk for oral complications associated

with cancer therapies. Soft-bristled toothbrushes and nonabrasive toothpaste

prevent or reduce trauma to the oral mucosa. Oral swabs with spongelike

applicators may be used in place of a toothbrush for painful oral tissues.

Flossing may be performed unless it causes pain or unless platelet levels are

below 40,000/mm3

(0.04 × 1012/L). Oral rinses with saline solution or tap

water may be necessary for patients who cannot tolerate a toothbrush. Products

that irritate oral tissues or impair healing, such as alcohol-based mouth

rinses, are avoided. Foods that are difficult to chew or are hot or spicy are

avoided to minimize further trauma. The pa-tient’s lips are lubricated to keep

them from becoming dry and cracked. Topical anti-inflammatory and anesthetic

agents may be prescribed to promote healing and minimize discomfort. Products

that coat or protect oral mucosa are used to promote comfort and prevent

further trauma. The patient who experiences severe pain and discomfort with

stomatitis requires systemic analgesics.

Adequate fluid and food intake is encouraged. In some in-stances,

parenteral hydration and nutrition are needed. Topical or systemic antifungal

and antibiotic medications are prescribed to treat local or systemic

infections.

MAINTAINING TISSUE INTEGRITY

Some of the most frequently encountered disturbances of tissue

integrity, in addition to stomatitis, include skin and tissue reac-tions to

radiation therapy, alopecia, and metastatic skin lesions.

The patient who is experiencing skin and tissue reactions to radiation

therapy requires careful skin care to prevent further skin irritation, drying,

and damage. The skin over the affected area is handled gently; rubbing and use

of hot or cold water, soaps, pow-ders, lotions, and cosmetics are avoided. The

patient may avoid tissue injury by wearing loose-fitting clothes and avoiding

clothes that constrict, irritate, or rub the affected area. If blistering

oc-curs, care is taken not to disrupt the blisters, thus reducing the risk of

introducing bacteria. Moisture- and vapor-permeable dressings, such as

hydrocolloids and hydrogels, are helpful in pro-moting healing and reducing

pain. Aseptic wound care is indi-cated to minimize the risk for infection and

sepsis. Topical antibiotics, such as 1% silver sulfadiazine cream (Silvadene),

may be prescribed for use on areas of moist desquamation (painful, red, moist

skin).

ASSISTING PATIENTS TO COPE WITH ALOPECIA

The temporary or permanent thinning or complete loss of hair is a

potential adverse effect of various radiation therapies and chemotherapeutic

agents. The extent of alopecia depends on the dose and duration of therapy.

These treatments cause alope-cia by damaging stem cells and hair follicles. As

a result, the hair is brittle and may fall out or break off at the surface of

the scalp. Loss of other body hair is less frequent. Hair loss usually begins

within 2 to 3 weeks after the initiation of treatment; regrowth begins within 8

weeks after the last treatment. Some patients who undergo radiation to the head

may sustain permanent hair loss. Many health care providers view hair loss as a

minor prob-lem when compared with the potentially life-threatening

con-sequences of cancer. For many patients, however, hair loss is a major

assault on body image, resulting in depression, anxiety, anger, rejection, and

isolation. To patients and families, hair loss can serve as a constant reminder

of the challenges cancer places on their coping abilities, interpersonal

relationships, and sexuality.

The nurse’s role is to provide information about alopecia and to support

the patient and family in coping with disturbing ef-fects of therapy, such as

hair loss and changes in body image. Pa-tients are encouraged to acquire a wig

or hairpiece before hair loss occurs so that the replacement matches their own

hair. Use of at-tractive scarves and hats may make the patient feel less

conspicu-ous. Nurses can refer patients to supportive programs, such as “Look

Good, Feel Better,” offered by the American Cancer Society. Knowledge that hair usually begins to

regrow after complet-ing therapy may comfort some patients, although the color

and texture of the new hair may be different.

MANAGING MALIGNANT SKIN LESIONS

Skin lesions may occur with local extension of the tumor or

em-bolization of the tumor into the epithelium and its surrounding lymph and

blood vessels. Secondary growth of cancer cells into the skin may result in

redness (erythematous areas) or can progress to wounds involving tissue

necrosis and infection. The most extensive lesions tend to disintegrate and are

purulent and malodorous. In addition, these lesions are a source of

consider-able pain and discomfort. Although this type of lesion is most often

associated with breast cancer and head and neck cancers, it can also occur with

lymphoma, leukemia, melanoma, and can-cers of the lung, uterus, kidney, colon,

and bladder. The devel-opment of severe skin lesions is usually associated with

a poor prognosis for extended survival.

Ulcerating skin lesions usually indicate widely disseminated disease

unlikely to be eradicated. Managing these lesions becomes a nursing priority.

Nursing care includes carefully assessing and cleansing the skin, reducing

superficial bacteria, controlling bleeding, reducing odor, and protecting the

skin from pain and further trauma. The patient and family require assistance

and guidance to care for these skin lesions at home. Referral for home care is

indicated.

PROMOTING NUTRITION

Most cancer patients experience some weight loss during their ill-ness.

Anorexia, malabsorption, and cachexia are examples of nu-tritional problems

that commonly occur in cancer patients; special attention is needed to prevent

weight loss and promote nutrition.

Anorexia

Among the many causes of anorexia in the cancer patient are alterations

in taste, manifested by increased salty, sour, and metal-lic taste sensations,

and altered responses to sweet and bitter flavors, leading to decreased

appetite, decreased nutritional in-take, and protein-calorie malnutrition.

Taste alterations may re-sult from mineral (eg, zinc) deficiencies, increases

in circulating amino acids and cellular metabolites, or the administration of

chemotherapeutic agents. Patients undergoing radiation therapy to the head and

neck may experience “mouth blindness,” which is a severe impairment of taste.

Alterations in the sense of smell also alter taste; this is a com-mon

experience of patients with head and neck cancers. Anorexia may occur because

the person feels full after eating only a small amount of food. This sense of

fullness occurs secondary to a de-crease in digestive enzymes, abnormalities in

the metabolism of glucose and triglycerides, and prolonged stimulation of

gastric volume receptors, which convey the feeling of being full.

Psy-chological distress, such as fear, pain, depression, and isolation,

throughout illness may also have a negative impact on appetite. The person may

develop an aversion to food because of nausea and vomiting after treatment.

Malabsorption

Many cancer patients are unable to absorb nutrients from the

gas-trointestinal system as a result of tumor activity and cancer treat-ment.

Tumors can affect the gastrointestinal activity in several ways. They may

impair enzyme production or produce fistulas. They secrete hormones and

enzymes, such as gastrin; this leads toincreased gastrointestinal irritation, peptic

ulcer disease, and de-creased fat digestion. They also interfere with protein

digestion.

Chemotherapy and radiation can irritate and damage mu-cosal cells of the

bowel, inhibiting absorption. Radiation ther-apy can cause sclerosis of the

blood vessels in the bowel and fibrotic changes in the gastrointestinal tissue.

Surgical interven-tion may change peristaltic patterns, alter gastrointestinal

secre-tions, and reduce the absorptive surfaces of the gastrointestinal mucosa,

all leading to malabsorption.

Cachexia

Cachexia is common in patients with cancer, especially in ad-vanced

disease. Cancer cachexia is related to inadequate nutri-tional intake along

with increasing metabolic demand, increased energy expenditure due to anaerobic

metabolism of the tumor, impaired glucose metabolism, competition of the tumor

cells for nutrients, altered lipid metabolism, and a suppressed appetite. It is

characterized by loss of body weight, adipose tissue, visceral protein, and

skeletal muscle. Patients who are cachectic complain of loss of appetite, early

satiety, and fatigue. As a result of protein losses they are often anemic and

have peripheral edema.

General Nutritional Considerations

Whenever possible, every effort is used to maintain adequate nu-trition

through the oral route. Food should be prepared in ways that make it appealing.

Unpleasant smells and unappetizing-looking foods are avoided. Family members

are included in the plan of care to encourage adequate food intake. The

patient’s preferences, as well as physiologic and metabolic requirements, are

considered when selecting foods. Small, frequent meals are provided, with

supplements between meals. Patients often toler-ate larger amounts of food

earlier in the day rather than later, so meals can be planned accordingly.

Patients should avoid drink-ing fluids while eating, to avoid early satiety.

Oral hygiene before mealtime often makes meals more pleasant. Pain, nausea, and

other symptoms that may interfere with nutrition are assessed and managed.

Medications such as corticosteroids or progestational agents such as megestrol

acetate have been used successfully as appetite stimulants.

If adequate nutrition cannot be maintained by oral intake, nu-tritional

support via the enteral route may be necessary. Short-term nutritional

supplementation may be provided through a nasogastric tube. However, if

nutritional support is needed be-yond several weeks, a gastrostomy or

jejunostomy tube may be inserted. Patients and families are taught to

administer enteral nutrition in the home setting.

If malabsorption is a

problem, enzyme and vitamin replace-ment may be instituted. Additional

strategies include changing the feeding schedule, using simple diets, and

relieving diarrhea. If malabsorption is severe, parenteral nutrition (PN) may

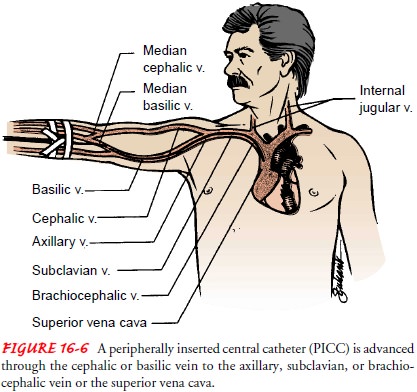

be nec-essary. PN can be administered in several ways: by a long-term venous

access device, such as a right atrial catheter, an implanted venous port, or a

peripherally inserted central catheter (Fig. 16-6). The nurse teaches the

patient and family to care for venous access devices and to administer PN. Home

care nurses may assist with or supervise PN in the home.

Interventions to reduce cachexia usually do not prolong sur-vival but may improve the patient’s quality of life. Before inva-sive nutritional strategies are instituted, the nurse should assess the patient carefully and discuss the options with the patient and family. Creative dietary therapies, enteral (tube) feedings, or PN may be necessary to ensure adequate nutrition. Nursing care is also directed toward preventing trauma, infection, and other complications that increase metabolic demands.

RELIEVING PAIN

Of all patients with

progressive cancer, more than 75% experi-ence pain (Yarbro, Hansen-Frogge &

Goodman, 1999). Although patients with cancer may have acute pain, their pain

is more frequently characterized as chronic. As in other situations in-volving

pain, the experience of cancer pain is influenced by both physical and

psychosocial factors.

Cancer can cause pain in various ways (Table 16-9). Pain is also

associated with various cancer treatments. Acute pain is linked with trauma from

surgery. Occasionally, chronic pain syn-dromes, such as postsurgical

neuropathies (pain related to nerve tissue injury), occur. Some

chemotherapeutic agents cause tissue necrosis, peripheral neuropathies, and

stomatitis—all potential sources of pain—whereas radiation therapy can cause

pain sec-ondary to skin or organ inflammation. Cancer patients may have other

sources of pain, such as arthritis or migraine headaches, that are unrelated to

the underlying cancer or its treatment.

In today’s society, most people expect pain to disappear or re-solve

quickly, and in fact it usually does. Although controllable, cancer pain is

commonly irreversible and not quickly resolved.For many patients, pain is a

signal that the tumor is growing and that death is approaching. As the patient

anticipates the pain and anxiety increases, pain perception heightens,

producing fear and further pain. Chronic cancer pain, then, can be best

de-scribed as a cycle progressing from pain to anxiety to fear and back to pain

again.

Pain tolerance, the point past which pain can no longer be tol-erated,

varies among people. Pain tolerance is decreased by fa-tigue, anxiety, fear of

death, anger, powerlessness, social isolation, changes in role identity, loss

of independence, and past experi-ences. Adequate rest and sleep, diversion,

mood elevation, empa-thy, and medications such as antidepressants, antianxiety

agents, and analgesics enhance tolerance to pain.

Inadequate pain management is most often the result of mis-conceptions

and insufficient knowledge about pain assessment and pharmacologic

interventions on the part of patients, fami-lies, and health care providers.

Successful management of cancer pain is based on thorough and objective pain

assessment that ex-amines physical, psychosocial, environmental, and spiritual

fac-tors. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential to determine optimal

management of the patient’s pain. Unlike instances of chronic nonmalignant

pain, systemic analgesics play a central role in managing cancer pain.

The World Health Organization (Dalton & Youngblood, 2000) advocates

a three-step approach to treating cancer pain. Analgesics are administered

based on the pa-tient’s level of pain. Nonopioid analgesics (eg, acetaminophen)

are used for mild pain; weak opioid analgesics (eg, codeine) are used for

moderate pain; and strong opioid analgesics (eg, mor-phine) are used for severe

pain. If the patient’s pain escalates, the strength of the analgesic medication

is increased until the pain is controlled. Adjuvant medications are also

administered to en-hance the effectiveness of analgesics and to manage other

symp-toms that may contribute to the pain experience. Examples of adjuvant

medications include antiemetics, antidepressants, anx-iolytics, antiseizure

agents, stimulants, local anesthetics, radio-pharmaceuticals (radioactive

agents that may be used to treat painful bone tumors), and corticosteroids.

Preventing and reducing

pain help to decrease anxiety and break the pain cycle. This can be

accomplished best by admin-istering analgesics on a regularly scheduled basis

as prescribed (the preventive approach to pain management), with additional

analgesics administered for breakthrough pain as needed and as prescribed.

Various pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches offer the best methods of managing cancer pain. No reasonable approaches, even those that may be invasive, should be over looked because of a poor or terminal prognosis.

Nurses help pa-tients and families to take an active

role in managing pain. Nurses provide education and support to correct fears

and misconcep-tions about opioid use. Inadequate pain control leads to

suffer-ing, anxiety, fear, immobility, isolation, and depression. Improving a

patient’s quality of life is as important as preventing a painful death.

DECREASING FATIGUE

In recent years, fatigue has been recognized as one of the most

sig-nificant and frequent symptoms experienced by patients receiving cancer

therapy. Nurses help the patient and family to understand that fatigue is

usually an expected and temporary side effect of the cancer process and of many

treatments used. Fatigue also stems from the stress of coping with cancer. It

does not always signify that the cancer is advancing or that the treatment is

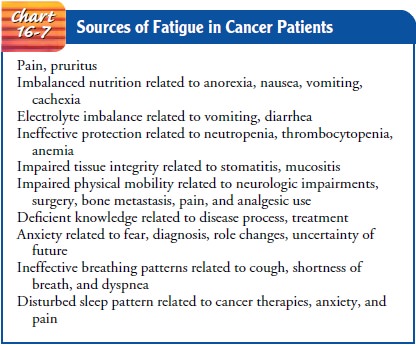

failing. Po-tential sources of fatigue are summarized in Chart 16-7.

Nursing strategies are

implemented to minimize fatigue or as-sist the patient to cope with existing

fatigue. Helping the patient to identify sources of fatigue aids in selecting

appropriate and in-dividualized interventions. Ways to conserve energy are

developed to help the patient plan daily activities. Alternating periods of

rest and activity are beneficial. Regular, light exercise may decrease fa-tigue

and facilitate coping, whereas lack of physical activity and “too much rest”

can actually contribute to deconditioning and as-sociated fatigue.

Patients are encouraged

to maintain as normal a lifestyle as possible by continuing with those

activities they value and enjoy. Prioritizing necessary and valued activities

can assist patients in planning for each day. Both patients and families are

encouraged to plan to reallocate responsibilities, such as attending to child

care, cleaning, and preparing meals. Patients who are employed full-time may

need to reduce the number of hours worked each week. The nurse assists the

patient and family in coping with these changing roles and responsibilities.

Nurses also address factors that contribute to fatigue and implement pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies to manage pain. Nutrition counseling is provided to patients who are not eating enough calories or protein. Small, frequent meals require less energy for digestion. Serum hemoglobin and hemat-ocrit levels are monitored for deficiencies, and blood products or EPO are administered as prescribed. Patients are monitored for alterations in oxygenation and electrolyte balances. Physical therapy and assistive devices are beneficial for patients with impaired mobility.

IMPROVING BODY IMAGE AND SELF-ESTEEM

A positive approach is essential when caring for the patient with an

altered body image. To help the patient retain control and positive

self-esteem, it is important to encourage independence and con-tinued

participation in self-care and decision making. The patient should be assisted

to assume those tasks and participate in those ac-tivities that are personally

of most value. Any negative feelings that the patient has or threats to body

image should be identified and discussed. The nurse serves as a listener and

counselor to both the patient and the family. Referral to a support group can

provide the patient with additional assistance in coping with the changes

re-sulting from cancer or its treatment. In many cases, a cosmetolo-gist can

provide ideas about hair or wig styling, make-up, and the use of scarves and

turbans to help with body image concerns.

Patients who experience alterations in sexuality and sexual function are

encouraged to discuss concerns openly with their partner. Alternative forms of

sexual expression are explored with the patient and partner to promote positive

self-worth and ac-ceptance. The nurse who identifies serious physiologic,

psycho-logical, or communication difficulties related to sexuality or sexual

function is in a key position to assist the patient and part-ner to seek

further counseling if necessary.

ASSISTING IN THE GRIEVING PROCESS

A cancer diagnosis need not indicate a fatal outcome. Many forms of

cancer are curable; others may be cured if treated early. Despite these facts,

many patients and their families view cancer as a fatal disease that is

inevitably accompanied by pain, suffering, debil-ity, and emaciation. Grieving

is a normal response to these fears and to the losses anticipated or

experienced by the patient with cancer. These may include loss of health,

normal sensations, body image, social interaction, sexuality, and intimacy. The

patient, family, and friends may grieve for the loss of quality time to spend

with others, the loss of future and unfulfilled plans, and the loss of control

over one’s own body and emotional reactions.

The patient and family

just informed of the cancer diagnosis frequently respond with shock, numbness,

and disbelief. It is often during this stage that the patient and family are

called on to make important initial decisions about treatment. They re-quire

the support of the physician, nurse, and other health care team members to make

these decisions. An important role of the nurse is to answer any questions the

patient and family have and clarify information provided by the physician.

In addition to assessing

the response of the patient and family to the diagnosis and planned treatment,

the nurse assists them in framing their questions and concerns, identifying

resources and support people (eg, spiritual advisor, counselor), and

communi-cating their concerns with each other. Support groups for patients and

families are available through hospitals and various commu-nity organizations.

These groups provide direct assistance, advice, and emotional support.

As the patient and family progress through the grieving process, they

may express anger, frustration, and depression. Dur-ing this time, the nurse

encourages the patient and family to ver-balize their feelings in an atmosphere

of trust and support. The nurse continues to assess their reactions and

provides assistance and support as they confront and learn to deal with new

problems.

If the patient enters the terminal phase of disease, the nurse may

realize that the patient and family members are at different stages of grief.

In such cases, the nurse assists the patient and family to acknowledge and cope

with their reactions and feelings. Nurses also assist patients and families to

explore preferences for issues related to end-of-life care such as withdrawal

of active disease treatment, desire for the use of life support measures, and

symptom manage-ment. Support, which can be as simple as holding the patient’s

hand or just being with the patient at home or at the bedside, often

contributes to peace of mind. Maintaining contact with the sur-viving family

members after the death of the cancer patient may help them to work through

their feelings of loss and grief.

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Despite advances in cancer care, infection remains the leading cause of

death. In the cancer patient, defense against infection is compromised in many

different ways. The integrity of the skin and mucous membrane, the body’s first

line of defense, is chal-lenged by multiple invasive diagnostic and therapeutic

proce-dures, by adverse effects of radiation and chemotherapy, and by the

detrimental effects of immobility.

Impaired nutrition resulting from anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,

and the underlying disease alters the body’s ability to combat invading

organisms. Medications such as antibiotics dis-turb the balance of normal

flora, allowing the overgrowth of path-ogenic organisms. Other medications can

also alter the immune response. Cancer itself may be immunosuppres-sive.

Cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma are often associ-ated with defects in

cellular and humoral immunity. Advanced cancer can lead to obstruction by the

tumor of the hollow viscera (such as the intestines), blood vessels, and lymphatic

vessels, cre-ating a favorable environment for proliferation of pathogenic

organisms. In some patients, tumor cells infiltrate bone marrow and prevent

normal production of WBCs. Most often, however, a decrease in WBCs is a result

of bone marrow suppression after chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

The use of the

hematopoietic growth factors, also called colony-stimulating factors (see the

previous discussion of BRM therapy), has reduced the severity and duration of

neutropenia associated with myelosuppressive chemotherapy and radiation

therapy. The administration of these factors assists in reducing the risk for

infection and, possibly, in maintaining treatment schedules, drug dosages,

treatment effectiveness, and the quality of life.

Infection

Gram-positive organisms, such as Streptococcus

and Staphylococcus species, are the

most frequently isolated causes of infection. Gram-negative organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonasaeruginosa, and fungal

organisms, such as Candida albicans, alsocontribute

to the incidence of serious infection.

Fever is probably the

most important sign of infection in the immunocompromised patient. Although

fever may be related to a variety of noninfectious conditions, including the

underlying cancer, any temperature of 38.3°C (101°F) or

higher is reported and dealt with promptly.

Antibiotics may be prescribed to treat infections after cultures of

wound drainage, exudate, sputum, urine, stool, or blood are obtained. Patients

with neutropenia are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics before the

infecting organism is identified because of the high incidence of mortality

associated with un-treated infection. Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage or

empiric therapy most often includes a combination of medications todefend the body against

the major pathogenic organisms. An important component of the nurse’s role is

to administer these medications promptly according to the prescribed schedule

to achieve adequate blood levels of the medications.

Strict asepsis is essential when handling intravenous lines, catheters,

and other invasive equipment. Exposure of the patient to others with an active

infection and to crowds is avoided. Pa-tients with profound immunosuppression,

such as BMT recipi-ents, may need to be placed in a protective environment

where the room and its contents are sterilized and the air is filtered. These

patients may also receive low-bacteria diets, avoiding fresh fruits and

vegetables. Hand hygiene and appropriate general hygiene are necessary to

reduce exposure to potentially harmful bacteria and to eliminate environmental

contaminants. Invasive procedures, such as injections, vaginal or rectal

examinations, rectal temperatures, and surgery, are avoided. The patient is

encouraged to cough and perform deep-breathing exercises fre-quently to prevent

atelectasis and other respiratory problems. Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy

may be used for patients who are expected to be profoundly immunosuppressed and

at risk for certain infections. The nurse teaches the patient and family to

recognize signs and symptoms of infection to report, perform effective hand

hygiene, use antipyretics, maintain skin integrity, and administer

hematopoietic growth factors when indicated.

Septic Shock

The nurse assesses the patient frequently for infection and

in-flammation throughout the course of the disease. Septicemia and septic shock

are life-threatening complications that must be pre-vented or detected and

treated promptly. Patients with signs and symptoms of impending sepsis and septic

shock require immedi-ate hospitalization and aggressive treatment.

Signs and symptoms of

septic shock include al-tered mental

status, either subnormal or elevated temperature, cool and clammy skin,

decreased urine output, hypotension, dys-rhythmias, electrolyte imbalances, and

abnormal arterial blood gas values. The patient and family members are

instructed about signs of septicemia, methods for preventing infection, and

actions to take if infection or septicemia occurs.

Septic shock is most often associated with overwhelming gram-negative

bacterial infections. The nurse monitors the blood pressure, pulse rate,

respirations, and temperature of the patient with shock every 15 to 30 minutes.

Neurologic assess-ments are carried out to detect changes in orientation and

re-sponsiveness. Fluid and electrolyte status is monitored by measuring fluid

intake and output and serum electrolytes. Arte-rial blood gas values and pulse

oximetry are monitored to deter-mine tissue oxygenation. The nurse administers

intravenous fluids, blood products, and vasopressors as prescribed to main-tain

the patient’s blood pressure and tissue perfusion. Supple-mental oxygen is

often necessary. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered as prescribed to

combat the underlying infection.

Bleeding and Hemorrhage

Thrombocytopenia, a

decrease in the circulating platelet count, is the most common cause of

bleeding in cancer patients and is usually defined as a count of less than

100,000/mm3 (0.1 × 1012/L). When the count falls

between 20,000 and 50,000/mm3 (0.02 to 0.05 × 1012/L), the

risk for bleeding increases. Counts under 20,000/mm3 (0.02 × 1012/L) are

associated with an in-creased risk for spontaneous bleeding, for which the

patient re-quires a platelet transfusion. Platelets are essential for normal

blood clotting and coagulation (hemostasis). Thrombocytopenia often results

from bone marrow depres-sion after certain types of chemotherapy and radiation

therapy. Tumor infiltration of the bone marrow can also impair the nor-mal

production of platelets. In some cases, platelet destruction is associated with

an enlarged spleen (hypersplenism) and abnormal antibody function that occur

with leukemia and lymphoma.

In addition to monitoring laboratory values, the

nurse con-tinues to assess the patient for bleeding. The nurse also takes steps

to prevent trauma and minimize the risk for bleeding by encour-aging the

patient to use a soft, not stiff, toothbrush and an elec-tric, not

straight-edged, razor. Additionally, the nurse avoids unnecessary invasive

procedures (eg, rectal temperatures, intra-muscular injections, and

catheterization) and assists the patient and family to identify and remove

environmental hazards that may lead to falls or other trauma. Soft foods,

increased fluid in-take, and stool softeners, if prescribed, may be indicated

to reduce trauma to the gastrointestinal tract. The joints and extremities are

handled and moved gently to minimize the risk for spontaneous bleeding. The

nurse may administer IL-11, which has been ap-proved by the FDA (Rust, Wood

& Battiato, 1999) to prevent severe thrombocytopenia and to reduce the need

for platelet transfusions following myelosuppressive chemotherapy in pa-tients

with nonmyeloid malignancies. In some instances, the nurse teaches the patient

or family member to administer IL-11 in the home.

Hemorrhage may be related to various underlying

abnormal-ities, such as thrombocytopenia and coagulation disorders. These

clinical situations are often associated with the cancer itself or the adverse

effects of cancer treatments. Sites of hemorrhage may in-clude the

gastrointestinal, respiratory, and genitourinary tracts and the brain. Blood

pressure and pulse and respiratory rates are monitored every 15 to 30 minutes

when hospitalized patients ex-perience bleeding.

Serum hemoglobin and hematocrit are monitored

carefully for changes indicating blood loss. The nurse tests all urine, stool,

and emesis for occult blood. Neurologic assessments are per-formed to detect

changes in orientation and behavior. The nurse administers fluids and blood

products as prescribed to replace any losses. Vasopressor agents are

administered as prescribed to main-tain blood pressure and ensure tissue

oxygenation. Supplemental oxygen is used as necessary.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

Patients with cancer usually return home from acute care facili-ties or

receive treatment in the home or outpatient area rather than acute care

facilities. The shift from the acute care setting also shifts the responsibility

for care to the patient and family. As a re-sult, families and friends must

assume increased involvement in patient care, which requires teaching that

enables them to pro-vide care. Teaching initially focuses on providing

information needed by the patient and family to address the most immediate care

needs likely to be encountered at home.

Side effects of treatments and changes in the patient’s status that

should be reported are reviewed verbally and reinforced with writ-ten

information. Strategies to deal with side effects of treatment are discussed

with the patient and family. Other learning needs are identified based on the

priorities conveyed by the patient and family as well as on the complexity of

care provided in the home.

Technological advances allow home administration of chemo-therapy, PN,

blood products, parenteral antibiotics, and parenteral analgesics; management

of symptoms; and care of vascu-lar access devices. Although home care nurses

provide care and support for patients receiving this advanced technical care,

the patient and family need instruction and ongoing support that allow them to

feel comfortable and proficient in managing these treatments at home. Follow-up

visits and telephone calls from the nurse are often reassuring to the patient

and family and increase their comfort in dealing with complex and new aspects

of care. Continued contact facilitates evaluation of the patient’s progress and

ongoing needs.

Continuing Care

Referral for home care

is often indicated for the patient with can-cer. The responsibilities of the

home care nurse include assessing the home environment, suggesting

modifications in the home or in care to assist the patient and family in

addressing the patient’s physical needs, providing physical care, and assessing

the psy-chological and emotional impact of the illness on the patient and

family.

Assessing changes in the

patient’s physical status and report-ing relevant changes to the physician help

to ensure that appro-priate and timely modifications in therapy are made. The

home care nurse also assesses the adequacy of pain management and the

effectiveness of other strategies to prevent or manage the side ef-fects of

treatment modalities.

The patient’s and

family’s understanding of the treatment plan and management strategies is

assessed, and previous teach-ing is reinforced. The nurse often facilitates the

coordination of patient care by maintaining close communication with all health

care providers involved in the patient’s care. The nurse may make referrals and

coordinate available community resources (eg, local office of the American

Cancer Society, home aides, church groups, parish nurses, and support groups)

to assist patients and caregivers.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

For specific patient

outcomes, see the Plan of Nursing Care. Ex-pected patient outcomes may include:

·

Maintains integrity of oral mucous membranes

·

Maintains adequate tissue integrity

·

Maintains adequate nutritional status

·

Achieves relief of pain and discomfort

·

Demonstrates increased activity tolerance and

decreased fatigue

·

Exhibits improved body image and self-esteem

·

Progresses through the grieving process

·

Experiences no complications, such as infection, or

sepsis, and no episodes of bleeding or hemorrhage

Related Topics