Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Respiratory Care Modalities

Nursing Process: The Patient Undergoing Thoracic Surgery

NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT UNDERGOING THORACIC SURGERY

Postoperative Assessment

The

nurse monitors the heart rate and rhythm by auscultation and electrocardiography

because episodes of major dysrhythmias are common after thoracic and cardiac

surgery. In the immediate postoperative period, an arterial line may be

maintained to allow frequent monitoring of arterial blood gases, serum

electrolytes, hemoglobin and hematocrit values, and arterial pressure. Central

venous pressure may be monitored to detect early signs of fluid volume

disturbances. Central venous pressure monitoring devices are being used less

frequently and for shorter periods of time than in the past. Early extubation

from mechanical ventilation can also lead to earlier removal of arterial lines

(Zevola & Maier, 1999). Another important component of postoperative

assessment is to note the results of the preoperative evaluation of the

patient’s lung reserve by pulmonary function testing. A preoperative FEV1

of more than 2 L or more than 70% of predicted value indicates a good lung

reserve. Patients who have a postoperative predicted FEV1

of less than 40% of predicted value have a higher incidence of morbidity and

mortality (Scanlan, Wilkins & Stoller, 1999). This results in decreased

tidal volumes, placing the patient at risk for respiratory failure.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based

on the assessment data, the patient’s major postoperative nursing diagnoses may

include:

·

Impaired gas exchange related to

lung impairment and surgery

·

Ineffective airway clearance related

to lung impairment, anesthesia, and pain

·

Acute pain related to incision,

drainage tubes, and the sur-gical procedure

·

Impaired physical mobility of the

upper extremities related to thoracic surgery

·

Risk for imbalanced fluid volume

related to the surgical pro-cedure

·

Imbalanced nutrition, less than body

requirements related to dyspnea and anorexia

·

Deficient knowledge about self-care

procedures at home

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Based

on assessment data, potential complications may include:

·

Respiratory distress

·

Dysrhythmias

·

Atelectasis, pneumothorax, and

bronchopleural fistula

·

Blood loss and hemorrhage

·

Pulmonary edema

Planning and Goals

The

major goals for the patient may include improvement of gas exchange and

breathing, improvement of airway clearance, relief of pain and discomfort,

increased arm and shoulder mobility, main-tenance of adequate fluid volume and

nutritional status, under-standing of self-care procedures, and absence of

complications.

Nursing Interventions

IMPROVING GAS EXCHANGE AND BREATHING

Gas

exchange is determined by evaluating oxygenation and ven-tilation. In the

immediate postoperative period, this is achieved by measuring vital signs

(blood pressure, pulse, and respirations) at least every 15 minutes for the

first 1 to 2 hours, then less fre-quently as the patient’s condition

stabilizes.

Pulse

oximetry is used for continuous monitoring of the ade-quacy of oxygenation. It

is important to draw blood for arterial blood gas measurements early in the

postoperative period to es-tablish a baseline to assess the adequacy of

oxygenation and ven-tilation and the possible retention of CO2.

The frequency with which postoperative arterial blood gases are measured

depends on whether the patient is mechanically ventilated or exhibits signs of

respiratory distress; these measurements can help determine ap-propriate

therapy. It also is common practice for patients to have an arterial line in

place to obtain blood for blood gas measure-ments and to monitor blood pressure

closely. Hemodynamic monitoring may be used to assess hemodynamic stability.

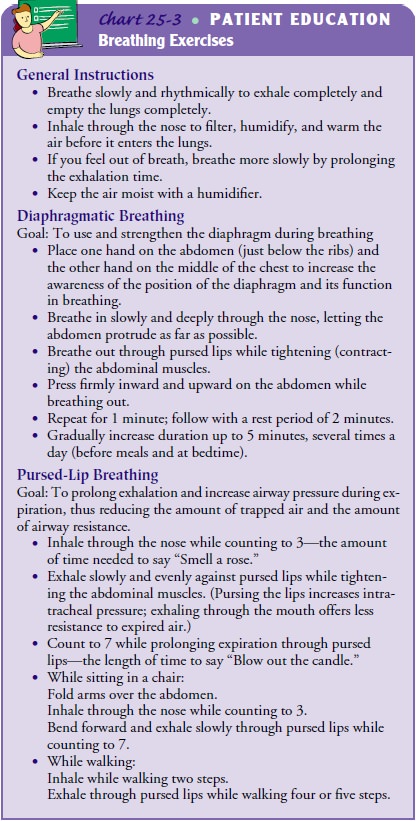

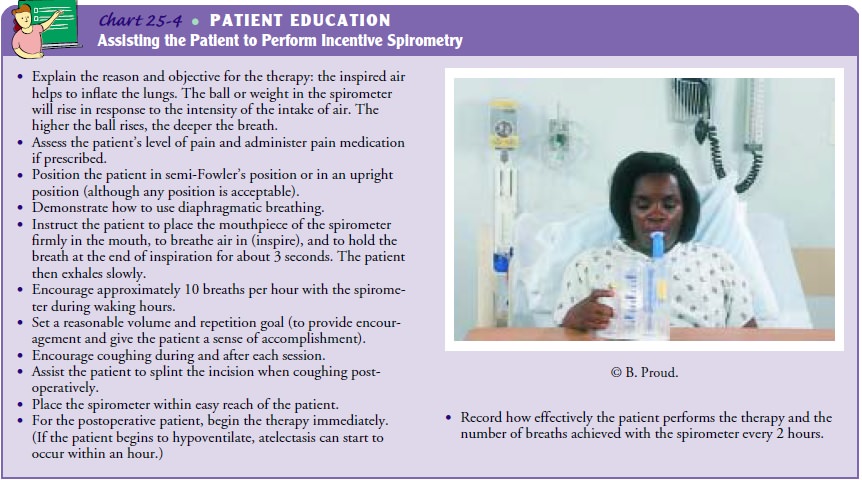

Breathing

techniques, such as diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breathing, that were taught

before surgery should be performed by the patient every 2 hours to expand the

alveoli and prevent at-electasis. Another technique to improve ventilation is

sustained maximal inspiration therapy or incentive spirometry. This tech-nique

promotes lung inflation, improves the cough mechanism, and allows early

assessment of acute pulmonary changes. (See Charts 25-3 and 25-4 for more

information.)

Positioning

also improves breathing. When the patient is ori-ented and blood pressure is

stabilized, the head of the bed is elevated 30 to 40 degrees during the

immediate postoperative period. This facilitates ventilation, promotes chest

drainage from the lower chest tube, and helps residual air to rise in the upper

portion of the pleural space, where it can be removed through the upper chest

tube.

The

nurse should consult with the surgeon about patient po-sitioning. There is

controversy regarding the best side-lying posi-tion. In general, the patient

should be positioned from back to side frequently and moved from horizontal to

semi-upright posi-tion as soon as tolerated. Most commonly, the patient is

in-structed to lie on the operative side. However, the patient with unilateral

lung pathology may not be able to turn well onto that side because of pain. In

addition, positioning the patient with the “good lung” (the nonoperated lung)

down allows a better match of ventilation and perfusion and therefore may

actually improve oxygenation. The patient’s position is changed from horizontal

to semi-upright as soon as possible, because remaining in one po-sition tends

to promote the retention of secretions in the depen-dent portion of the lungs.

After a pneumonectomy, the operated side should be dependent so that fluid in

the pleural space re-mains below the level of the bronchial stump, and the

other lung can fully expand.

The

procedure for turning the patient is as follows:

·

Instruct the patient to bend the

knees and use the feet to push.

·

Have the patient shift hips and

shoulders to the opposite side of the bed while pushing with the feet.

·

Bring the patient’s arm over the

chest, pointing it in the di-rection toward which the patient is being turned.

Have the patient grasp the side rail with the hand.

·

Turn the patient in log-roll fashion

to prevent twisting at the waist and pain from possible pulling on the

incision.

IMPROVING AIRWAY CLEARANCE

Retained

secretions are a threat to the thoracotomy patient after surgery. Trauma to the

tracheobronchial tree during surgery, di-minished lung ventilation, and

diminished cough reflex all result in the accumulation of excessive secretions.

If the secretions are retained, airway obstruction occurs. This, in turn,

causes the air in the alveoli distal to the obstruction to become absorbed and

the affected portion of the lung to collapse. Atelectasis, pneumo-nia, and

respiratory failure may result.

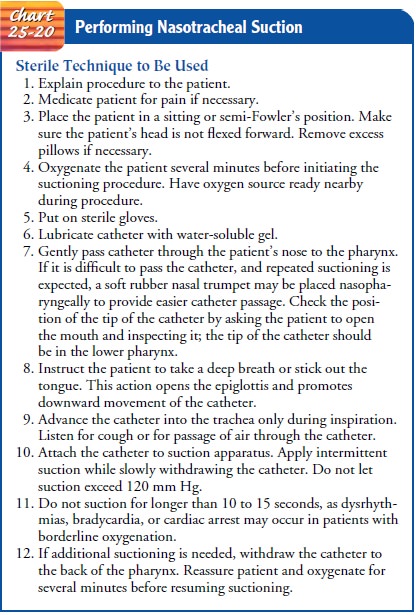

Several

techniques are used to maintain a patent airway. First, secretions are

suctioned from the tracheobronchial tree before the endotracheal tube is

discontinued. Secretions continue to be re-moved by suctioning until the

patient can cough up secretions ef-fectively. Nasotracheal suctioning may be

needed to stimulate a deep cough and aspirate secretions that the patient

cannot cough up. However, it should be used only after other methods to raise

secretions have been unsuccessful (Chart 25-20).

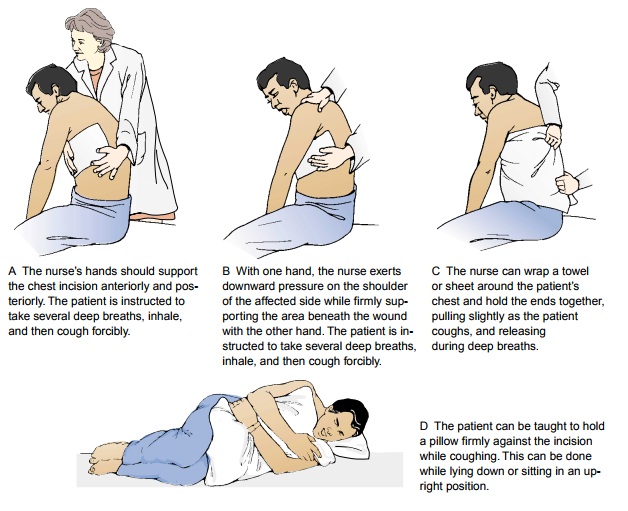

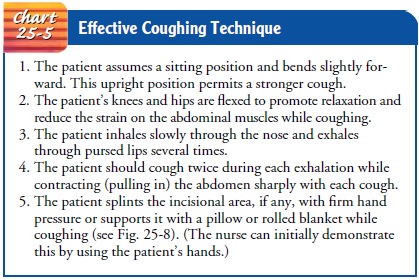

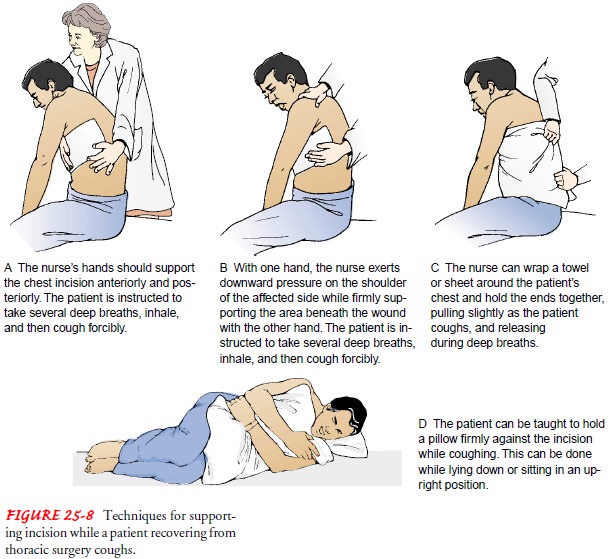

Coughing

technique is another measure used in maintaining a patent airway. The patient

is encouraged to cough effectively; in-effective coughing results in exhaustion

and retention of secretions (see Chart 25-5). To be effective, the cough must

be low-pitched, deep, and controlled. Because it is difficult to cough in a

supine position, the patient is helped to a sitting position on the edge of the

bed, with the feet resting on a chair. The patient should cough at least every

hour during the first 24 hours and when necessary thereafter. If audible

crackles are present, it may be necessary to use chest percussion with the

cough routine until the lungs are clear. Aerosol therapy is helpful in

humidifying and mobilizing secretions so that they can easily be cleared with

coughing. To min-imize incisional pain during coughing, the nurse supports the

in-cision or encourages the patient to do so (Fig. 25-8).

After

helping the patient to cough, the nurse should listen to both lungs, anteriorly

and posteriorly, to determine whether there are any changes in breath sounds.

Diminished breath sounds may indicate collapsed or hypoventilated alveoli.

Chest

physiotherapy is the final technique for maintaining a patent airway. If a

patient is identified as being at high risk for de-veloping postoperative

pulmonary complications, then chest phys-iotherapy is started immediately

(perhaps even before surgery). The techniques of postural drainage, vibration,

and percussion help to loosen and mobilize the secretions so that they can be

coughed up or suctioned.

RELIEVING PAIN AND DISCOMFORT

Pain

after a thoracotomy may be severe, depending on the type of incision and the

patient’s reaction to and ability to cope with pain. Deep inspiration is very

painful after thoracotomy. Pain can lead to postoperative complications if it

reduces the patient’s abil-ity to breathe deeply and cough, and if it further

limits chest ex-cursions so that ventilation becomes ineffective.

Immediately after the surgical procedure and before the incision is closed, the surgeon may perform a nerve block with a long-acting local anesthetic such as bupivacaine (Marcaine, Sensorcaine). Bupivacaine is titrated to relieve postoperative pain while allowing the patient to cooperate in deep breathing, coughing, and mobi-lization. However, it is important to avoid depressing the respira-tory system with excessive analgesia: the patient should not be so sedated as to be unable to cough. There is controversy about the ef-fectiveness of injections of local anesthetic for pain relief after tho-racotomy surgery. Research has shown that bupivacaine was no more effective than saline injections in treating postoperative tho-racotomy pain (Silomon et al., 2000).

Lidocaine

and prilocaine are local anesthetic agents used to treat pain at the site of

the chest tube insertion. These medica-tions are administered as topical

transdermal analgesics that pen-etrate the skin. Lidocaine and prilocaine have

also been found to be effective when used together. EMLA cream, which is a

mix-ture of the two medications, has been found to be effective in treating

pain from chest tube removal, and recent studies found it to be more effective

than intravenous morphine (Valenzuela & Rosen, 1999).

Because

of the need to maximize patient comfort without de-pressing the respiratory

drive, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is often used. Opioid analgesic

agents such as morphine are com-monly used. PCA, administered through an

intravenous pump or an epidural catheter, allows the patient to control the

frequency and total dosage. Preset limits on the pump avoid overdosage. With

proper instruction, these methods are well tolerated and allow earlier

mobilization and cooperation with the treatment regimen.

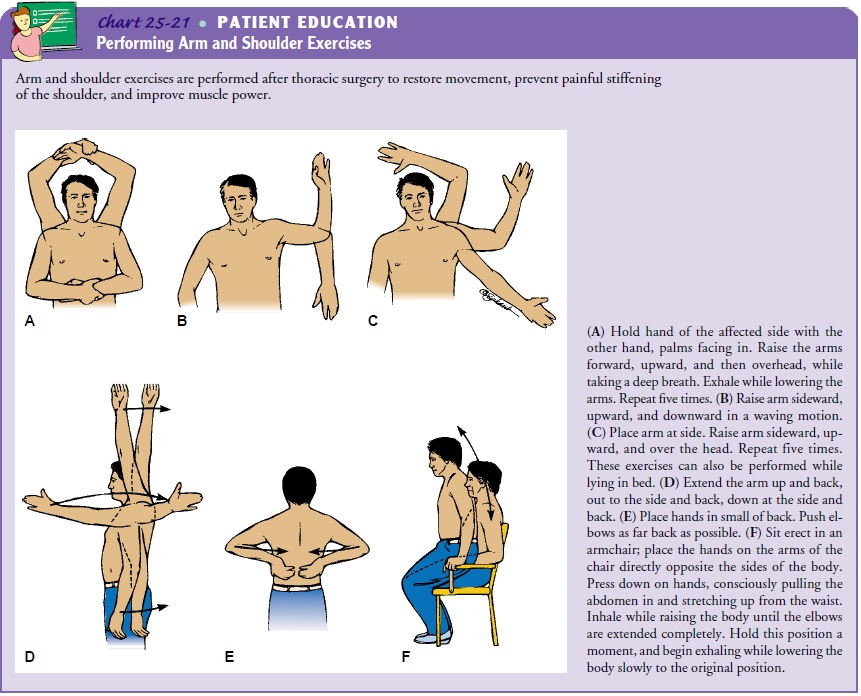

PROMOTING MOBILITY AND SHOULDER EXERCISES

Because

large shoulder girdle muscles are transected during a tho-racotomy, the arm and

shoulder must be mobilized by full range of motion of the shoulder. As soon as

physiologically possible, usually within 8 to 12 hours, the patient is helped

to get out of bed. Although this may be painful initially, the earlier the

patient moves, the sooner the pain will subside. In addition to getting out of

bed, the patient begins arm and shoulder exercises to restore movement and

prevent painful stiffening of the affected arm and shoulder (Chart 25-21).

MAINTAINING FLUID VOLUME AND NUTRITION

Intravenous Therapy

During

the surgical procedure or immediately after, the patient may receive a

transfusion of blood products, followed by a contin-uous intravenous infusion.

Because a reduction in lung capacity often occurs following thoracic surgery, a

period of physiologic ad-justment is needed. Fluids should be administered at a

low hourly rate and titrated (as prescribed) to prevent overloading the

vascu-lar system and precipitating pulmonary edema. The nurse performs careful

respiratory and cardiovascular assessments, as well as intake and output, vital

signs, and assessment of jugular vein distention. The nurse should also monitor

the infusion site for signs of infil-tration, including swelling, tenderness,

and redness.

Diet

It is not unusual for patients undergoing thoracotomy to have poor nutritional status before surgery because of dyspnea, sputum pro-duction, and poor appetite. Therefore, it is especially important that adequate nutrition be provided. A liquid diet is provided as soon as bowel sounds return; the patient is progressed to a full diet as soon as possible. Small, frequent meals are better tolerated and are crucial to the recovery and maintenance of lung function.

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Complications

after thoracic surgery are always a possibility and must be identified and

managed early. In addition, the nurse monitors the patient at regular intervals

for signs of respiratory distress or developing respiratory failure,

dysrhythmias, bron-chopleural fistula, hemorrhage and shock, atelectasis, and

pul-monary infection.

Respiratory

distress is treated by identifying and eliminating its cause while providing

supplemental oxygen. If the patient pro-gresses to respiratory failure,

intubation and mechanical ventila-tion are necessary, eventually requiring

weaning.

Dysrhythmias

are often related to the effects of hypoxia or the surgical procedure. They are

treated with antiarrhythmic med-ication and supportive therapy. Pulmonary

infections or effusion, often preceded by atelectasis, may occur a few days

into the postoperative course.

Pneumothorax

may occur following thoracic surgery if there is an air leak from the surgical

site to the pleural cavity or from the pleural cavity to the environment. Failure

of the chest drainage system will prevent return of negative pressure in the

pleural cavity and result in pneumothorax. In the postoperative patient

pneumothorax is often accompanied by hemothorax. The nurse maintains the chest

drainage system and monitors the patient for signs and symptoms of

pneumothorax: increasing shortness of breath, tachycardia, increased

respiratory rate, and increasing res-piratory distress.

Bronchopleural

fistula is a serious but rare complication pre-venting the return of negative

intrathoracic pressure and lung re-expansion. Depending on its severity, it is

treated with closed chest drainage, mechanical ventilation, and possibly talc

pleu-rodesis.

Hemorrhage

and shock are managed by treating the under-lying cause, whether by reoperation

or by administration of blood products or fluids. Pulmonary edema from

overinfusion of intra-venous fluids is a significant danger. The early symptoms

are dyspnea, crackles, bubbling sounds in the chest, tachycardia, and pink,

frothy sputum. This constitutes an emergency and must be reported and treated

immediately.

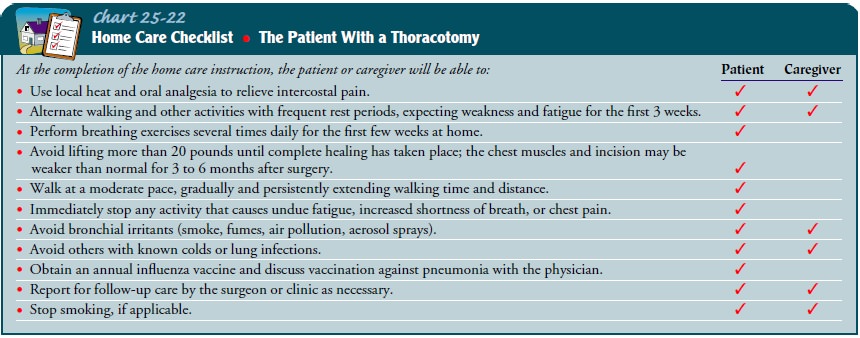

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

The

nurse instructs the patient and family about postoperative care that will be

continued at home. The nurse explains signs and symptoms that should be

reported to the physician. These include:

·

Change in respiratory status:

increasing shortness of breath, fever, increased restlessness or other changes

in mental or cognitive status, increased respiratory rate, change in

respi-ratory pattern, change in amount or color of sputum

·

Bleeding or other drainage from the

surgical incision or chest tube exit sites

·

Increased chest pain

In

addition, respiratory care and other treatment modalities (oxygen, incentive

spirometer, chest physiotherapy, and oral, in-haled, or intravenous

medications) may be continued at home. Therefore, the nurse needs to instruct

the patient and family in their correct and safe use.

The

nurse emphasizes the importance of progressively in-creased activity. The nurse

instructs the patient to ambulate within limits and explains that return of

strength is likely to be very gradual. Another important aspect of patient

teaching ad-dresses shoulder exercises. It is important to instruct the patient

to do these exercises five times daily. Additional patient teaching is

described in Chart 25-22.

Continuing Care

Depending

on the patient’s physical status and the availability of family assistance, a

home care referral may be indicated. The home care nurse assesses the patient’s

recovery from surgery, with special attention to respiratory status, the

surgical incision, chest drainage, pain control, ambulation, and nutritional

sta-tus. The patient’s use of respiratory modalities should be as-sessed to

ensure they are being used correctly and safely. In addition, the nurse

assesses the patient’s compliance with the postoperative treatment plan and

identifies acute or late post-operative complications.

The

recovery process may be longer than the patient had ex-pected, and providing

support to the patient is an important task for the home care nurse. Because of

shorter hospital stays, at-tending follow-up physician appointments is

essential. The nurse teaches the patient about the importance of keeping

follow-up appointments and completing laboratory tests as prescribed to as-sist

the physician in evaluating recovery. The home care nurse provides continuous

encouragement and education to the patient and family during the process. As

recovery progresses, the nurse also reminds the patient and family about the

importance of par-ticipating in health promotion activities and recommended

health screening.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected

patient outcomes may include:

·

Demonstrates improved gas exchange,

as reflected in arte-rial blood gas measurements, breathing exercises, and use

of incentive spirometry

·

Shows improved airway clearance, as

evidenced by deep, controlled coughing and clear breath sounds or decreased

presence of adventitious sounds

·

Has decreased pain and discomfort by

splinting incision during coughing and increasing activity level

·

Shows improved mobility of shoulder

and arm; demon-strates arm and shoulder exercises to relieve stiffening

·

Maintains adequate fluid intake and

maintains nutrition for healing

·

Exhibits less anxiety by using

appropriate coping skills, and demonstrates a basic understanding of technology

used in care

·

Adheres to therapeutic program and

home care

·

Is free of complications, as

evidenced by normal vital signs and temperature, improved arterial blood gas

measure-ments, clear lung sounds, and adequate respiratory function

For a detailed plan of nursing care for the patient who has had a thoracotomy, see the Plan of Nursing Care.

Related Topics