Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Respiratory Care Modalities

Airway Management

Airway Management

Adequate

ventilation is dependent on free movement of air through the upper and lower

airways. In many disorders, the air-way becomes narrowed or blocked as a result

of disease, bron-choconstriction (narrowing of airway by contraction of muscle

fibers), a foreign body, or secretions. Maintaining a patent (open) airway is

achieved through meticulous airway management, whether in an emergency

situation such as airway obstruction or in long-term management, as in caring

for a patient with an endotracheal or a tracheostomy tube.

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OF UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Upper

airway obstruction has a variety of causes. Acute upper air-way obstruction may

be caused by food particles, vomitus, blood clots, or any other particle that

enters and obstructs the larynx or trachea. It also may occur from enlargement

of tissue in the wall of the airway, as in epiglottitis, laryngeal edema,

laryngeal carci-noma, or peritonsillar abscess, or from thick secretions.

Pressure on the walls of the airway, as occurs in retrosternal goiter,

en-larged mediastinal lymph nodes, hematoma around the upper airway, and

thoracic aneurysm, also may result in upper airway obstruction.

The

patient with an altered level of consciousness from any cause is at risk for

upper airway obstruction because of loss of the protective reflexes (cough and

swallowing) and the tone of the pharyngeal muscles, causing the tongue to fall

back and block the airway.

The

nurse makes the following rapid observations to assess for signs and symptoms

of upper airway obstruction:

1.

Inspection—Is the patient conscious?

Is there any inspira-tory effort? Does the chest rise symmetrically? Is there

use or retraction of accessory muscles? What is the skin color? Are there any

obvious signs of deformity or obstruction (trauma, food, teeth, vomitus)? Is

the trachea midline?

2.

Palpation—Do both sides of the chest

rise equally with in-spiration? Are there any specific areas of tenderness,

frac-ture, or subcutaneous emphysema (crepitus)?

3.

Auscultation—Is there any audible

air movement, stridor (inspiratory sound), or wheezing (expiratory sound)? Are

breath sounds present bilaterally in all lobes?

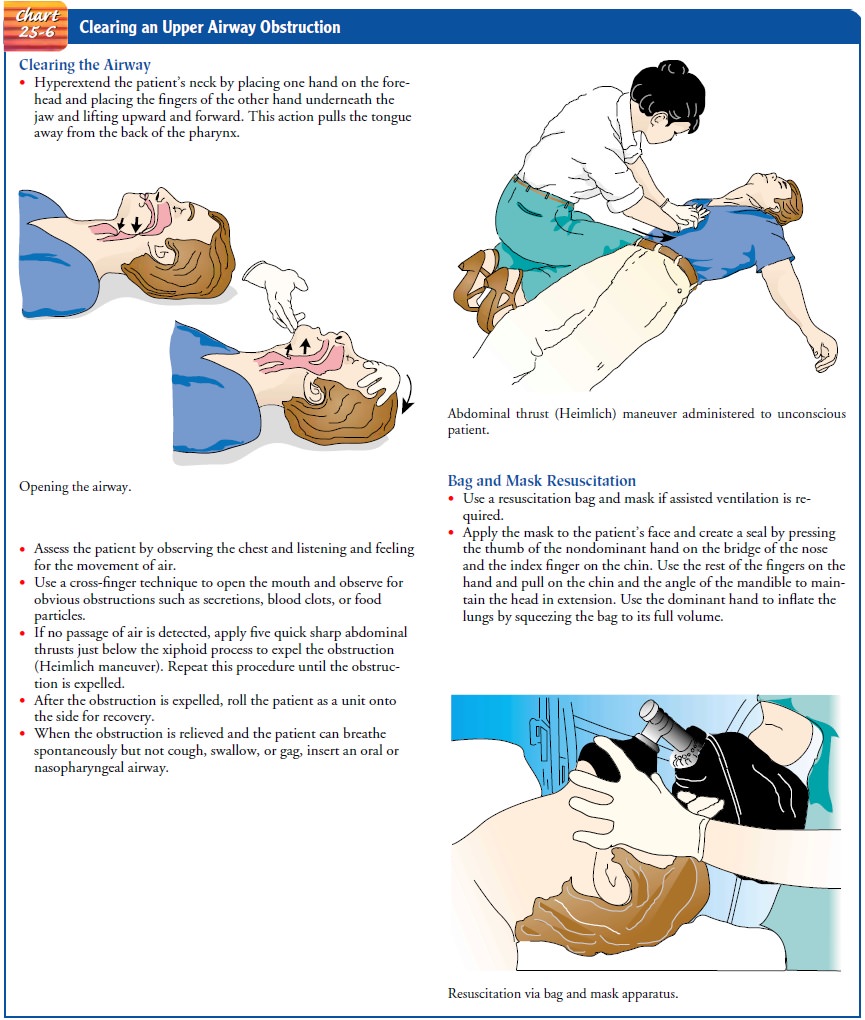

As

soon as an upper airway obstruction is identified, the nurse takes emergency

measures (Chart 25-6).

ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

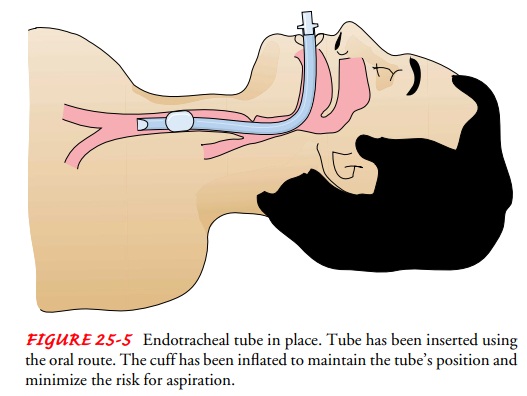

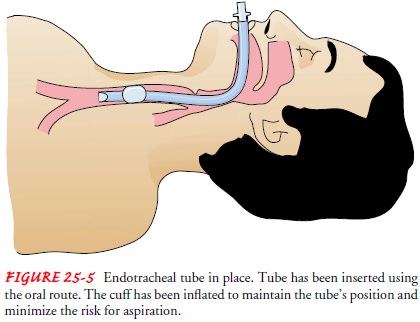

Endotracheal intubation involves

passing an endotracheal tubethrough the mouth or nose into the trachea (Fig.

25-5). Intuba-tion provides a patent airway when the patient is having

respira-tory distress that cannot be treated with simpler methods. It is the

method of choice in emergency care. Endotracheal intubation is a means of

providing an airway for patients who cannot maintain an adequate airway on

their own (eg, comatose patients or patients with upper airway obstruction),

for mechanical ventilation, and for suctioning secretions from the pulmonary

tree.

An

endotracheal tube usually is passed with the aid of a laryn-goscope by

specifically trained medical, nursing, or respiratory therapy personnel. Once

the tube is in-serted, a cuff around the tube is inflated to prevent air from

leaking around the outer part of the tube, to minimize the possibility of

subsequent aspiration, and to prevent movement of the tube.

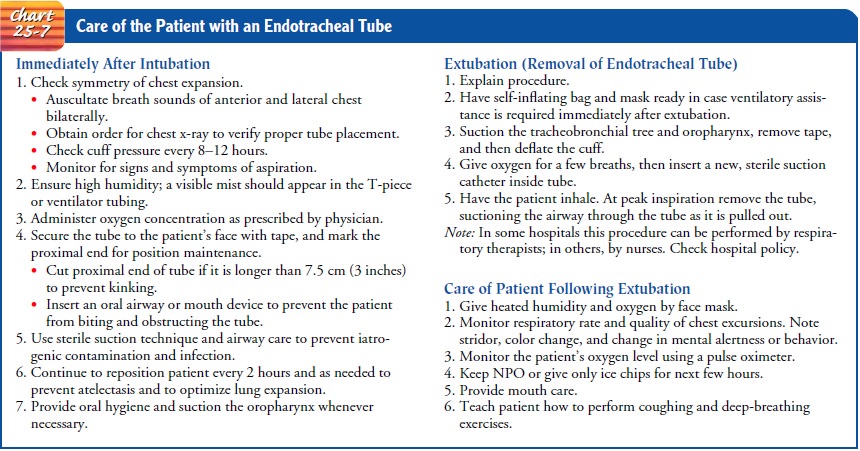

Nurses

should be aware that complications could occur from pressure in the cuff on the

tracheal wall. Cuff pressures should be checked with a calibrated aneroid manometer

device every 8 to 12 hours to maintain cuff pressure between 20 and 25 mm Hg.

High cuff pressure can cause tracheal bleeding, ischemia, and pressure

necrosis, while low cuff pressure can increase the risk of aspiration

pneumonia. Routine deflation of the cuff is not recommended due to the

increased risk of aspiration and hypoxia. The cuff is de-flated prior to

removing the endotracheal tube (St. John, 1999b).

Tracheobronchial

secretions are suctioned through the tube. Warmed, humidified oxygen should

always be introduced through the tube, whether the patient is breathing

spontaneously or is re-ceiving ventilatory support. Endotracheal intubation may

be used for no more than 3 weeks, by which time a tracheostomy must be

considered to decrease irritation of and trauma to the tracheal lin-ing, to

reduce the incidence of vocal cord paralysis (secondary to laryngeal nerve

damage), and to decrease the work of breathing. Chart 25-7 discusses the

nursing care of the patient with an en-dotracheal tube.

There

are several disadvantages of endotracheal and trache-ostomy tubes. First, the

tube causes discomfort. In addition, the cough reflex is depressed because

closure of the glottis is hindered. Secretions tend to become thicker because

the warming and hu-midifying effect of the upper respiratory tract has been

bypassed. The swallowing reflexes, composed of the glottic, pharyngeal, and

laryngeal reflexes, are depressed because of prolonged disuse and the

mechanical trauma of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, which puts the

patient at increased risk for aspiration. In addi-tion, ulceration and

stricture of the larynx or trachea may de-velop. Of great concern to the

patient is the inability to talk and to communicate needs.

Unintentional

or premature removal of the tube is a potentially life-threatening complication

of endotracheal intubation. Removal of the tube is a frequent problem in

intensive care units and occurs mainly during nursing care or by the patient.

It is important for nurses to instruct patients and family members about the

purpose of the tube and the dangers of removing it. Baseline and ongoing

assessment of the patient and equipment ensures effective care. Providing

comfort measures, including opioid analgesia and seda-tion, can improve the patient’s

tolerance of the endotracheal tube.

To prevent tube removal by the patient, the nurse can use the following strategies: explain to the patient and family the purpose of the tube, distract the patient through one-to-one interaction with the nurse and family or with television, and maintain com-fort measures. As a last resort, soft wrist restraints may be used, according to agency policy.

Studies have shown that the most effective way to prevent tube removal by the patient is through the use of soft wrist restraints (Happ, 2000). However, discretion and caution must always be used before applying any restraint. If the patient cannot move the arms and hands to the endotracheal tube, restraints would not be needed. If the patient is alert, oriented, able to follow directions, and cooperative to the point that it is highly unlikely that he or she will remove the endotracheal tube, restraints are not needed. On the other hand, if the nurse determines there is a risk that the patient may try to remove the tube, soft wrist restraints are appropriate with a physician’s order (check agency policy). Close monitoring of the patient remains essential to ensure safety and prevent harm.

TRACHEOSTOMY

A

tracheotomy is a surgical procedure

in which an opening is made into the trachea. The indwelling tube inserted into

the tra-chea is called a tracheostomy

tube. A tracheostomy may be either temporary or permanent.

A

tracheostomy is used to bypass an upper airway obstruction, to allow removal of

tracheobronchial secretions, to permit the long-term use of mechanical

ventilation, to prevent aspiration of oral or gastric secretions in the

unconscious or paralyzed patient (by closing off the trachea from the

esophagus), and to replace an endotracheal tube. There are many disease

processes and emer-gency conditions that make a tracheostomy necessary.

Procedure

The

surgical procedure is usually performed in the operating room or in an

intensive care unit, where the patient’s ventilation can be well controlled and

optimal aseptic technique can be maintained.A surgical opening is made in the

second and third tracheal rings. After the trachea is exposed, a cuffed

tracheostomy tube of an ap-propriate size is inserted. The cuff is an

inflatable attachment to the tracheostomy tube that is designed to occlude the

space be-tween the trachea walls and the tube to permit effective me-chanical

ventilation and to minimize the risk of aspiration.

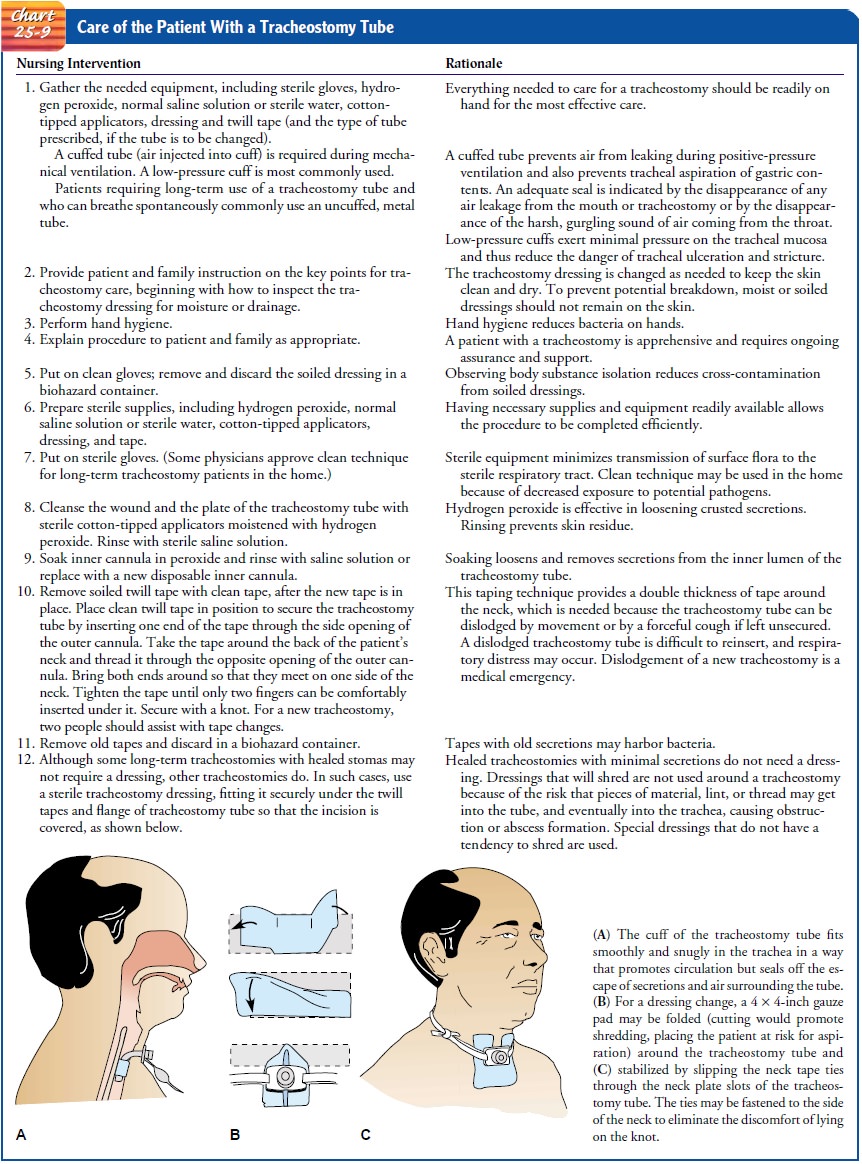

The

tracheostomy tube is held in place by tapes fastened around the patient’s neck.

Usually a square of sterile gauze is placed between the tube and the skin to

absorb drainage and pre-vent infection.

Complications

Complications

may occur early or late in the course of tra-cheostomy tube management. They

may even occur years after the tube has been removed. Early complications

include bleed-ing, pneumothorax, air embolism, aspiration, subcutaneous or

mediastinal emphysema, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, and posterior tracheal

wall penetration. Long-term complications in-clude airway obstruction from

accumulation of secretions or pro-trusion of the cuff over the opening of the

tube, infection, rupture of the innominate artery, dysphagia, tracheoesophageal

fistula, tracheal dilation, and tracheal ischemia and necrosis. Tracheal

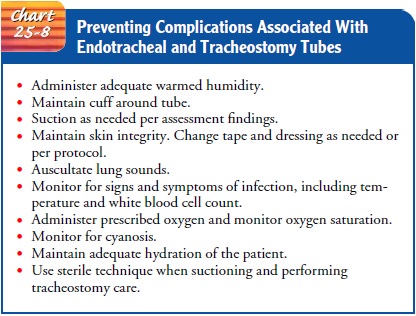

stenosis may develop after the tube is removed. Chart 25-8 out-lines measures

nurses can take to prevent complications.

Postoperative Nursing Management

The

patient requires continuous monitoring and assessment. The newly made opening

must be kept patent by proper suctioning of secretions. After the vital signs

are stable, the patient is placed in a semi-Fowler’s position to facilitate

ventilation, promote drainage, minimize edema, and prevent strain on the suture

lines. Analgesia and sedative agents must be administered with caution because

of the risk of suppressing the cough reflex.

Major objectives of nursing care are to alleviate the patient’s apprehension and to provide an effective means of communication.

The nurse keeps paper and pencil or a Magic Slate and the call light within the

patient’s reach to ensure a means of commu-nication. The care of the patient

with a tracheostomy tube is summarized in Chart 25-9.

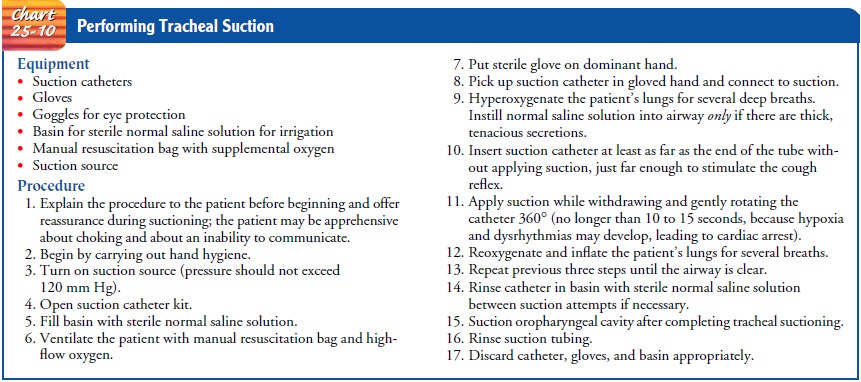

SUCTIONING THE TRACHEAL TUBE (TRACHEOSTOMY OR ENDOTRACHEAL TUBE)

When

a tracheostomy or endotracheal tube is in place, it is usu-ally necessary to

suction the patient’s secretions because of the de-creased effectiveness of the

cough mechanism. Tracheal suctioning is performed when adventitious breath

sounds are detected or whenever secretions are obviously present. Unnecessary

suction-ing can initiate bronchospasm and cause mechanical trauma to the

tracheal mucosa.

All

equipment that comes into direct contact with the pa-tient’s lower airway must

be sterile to prevent overwhelming pul-monary and systemic infections. The

procedure for suctioning a tracheostomy is presented in Chart 25-10. In

mechanically ven-tilated patients, an in-line suction catheter may be used to

allow rapid suction when needed and to minimize cross-contamination of airborne

pathogens. An in-line suction device allows the pa-tient to be suctioned

without being disconnected from the venti-lator circuit.

MANAGING THE CUFF

As

a general rule, the cuff on an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube should be

inflated. The pressure within the cuff should be the lowest possible that

allows delivery of adequate tidal volumes and prevents pulmonary aspiration.

Usually the pressure is main-tained at less than 25 cm H2O

to prevent injury and at more than 20 cm H2O

to prevent aspiration. Cuff pressure must be moni-tored at least every 8 hours

by attaching a hand-held pressure gauge to the pilot balloon of the tube or by

using the minimal leak volume or minimal occlusion volume technique. With

long-term intubation, higher pressures may be needed to maintain an adequate

seal.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care. If the patient is at home with a tra-cheostomy, the nurse

instructs the patient and family about its daily care as well as measures to

take in an emergency. The nurse also makes sure the patient and family are

aware of community contacts for education and support needs. It is important

for the nurse to teach the patient and family strategies to prevent

infec-tion when performing tracheostomy care (McConnell, 2000).

Related Topics