Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Respiratory Care Modalities

Chest Physiotherapy - Noninvasive Respiratory Therapies

CHEST PHYSIOTHERAPY

Chest physiotherapy (CPT)

includes postural drainage, chest

percussion and vibration, and

breathing exercises/breathing re-training. In addition, teaching the patient

effective coughing technique is an important part of chest physiotherapy. The

goals of chest physiotherapy are to remove bronchial secretions, im-prove

ventilation, and increase the efficiency of the respiratory muscles.

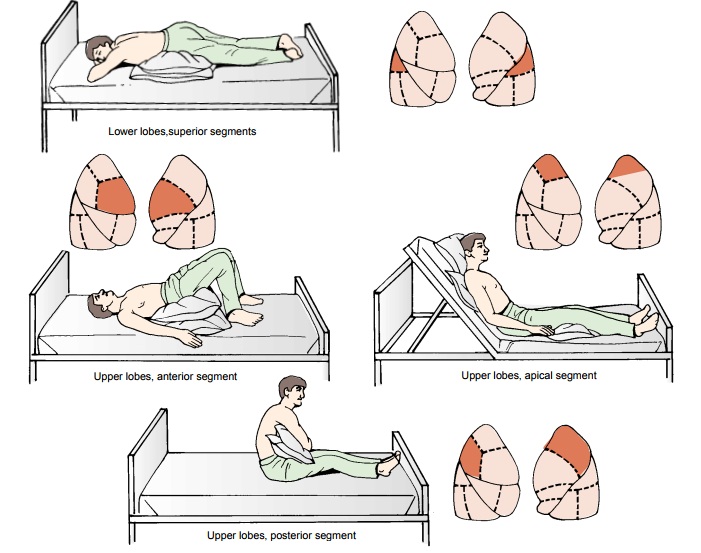

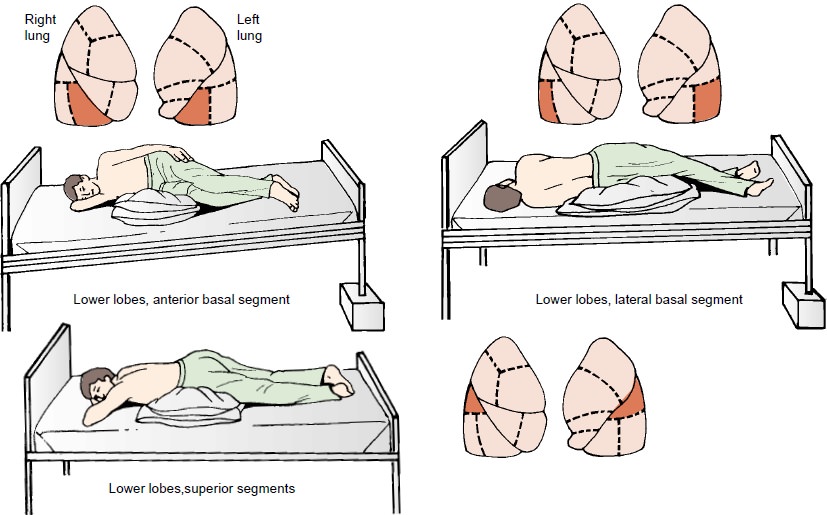

Postural Drainage (Segmented Bronchial Drainage)

Postural

drainage uses specific positions that allow the force of gravity to assist in

the removal of bronchial secretions. The se-cretions drain from the affected

bronchioles into the bronchi and trachea and are removed by coughing or

suctioning. Postural drainage is used to prevent or relieve bronchial

obstruction caused by accumulation of secretions.

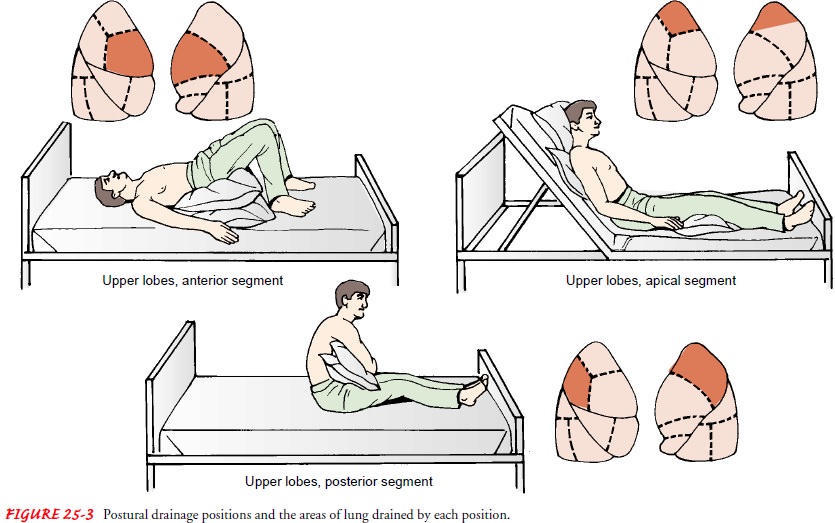

Because

the patient usually sits in an upright position, secre-tions are likely to

accumulate in the lower parts of the lungs. With postural drainage, different

positions (Fig. 25-3) are used so that the force of gravity helps to move secretions

from the smaller bronchial airways to the main bronchi and trachea. The

secre-tions then are removed by coughing. The nurse should instruct the patient

to inhale bronchodilators and mucolytic agents, if pre-scribed, before postural

drainage because these medications im-prove bronchial tree drainage.

Postural

drainage exercises can be directed at any of the seg-ments of the lungs. The

lower and middle lobe bronchi drain more effectively when the head is down; the

upper lobe bronchi drain more effectively when the head is up. Frequently, five

po-sitions are used, one for drainage of each lobe: head down, prone, right and

left lateral, and sitting upright.

Nursing Management

The

nurse should be aware of the patient’s diagnosis as well as the lung lobes or

segments involved, the cardiac status, and any struc-tural deformities of the

chest wall and spine. Auscultating the chest before and after the procedure

helps to identify the areas needing drainage and to assess the effectiveness of

treatment. The nurse teaches family members who will be assisting the patient

at home to evaluate breath sounds before and after treatment. The nurse

explores strategies that will enable the patient to assume the in-dicated

positions at home. This may require the creative use of objects readily

available at home, such as pillows, cushions, or card-board boxes.

Postural

drainage is usually performed two to four times daily, before meals (to prevent

nausea, vomiting, and aspiration) and at bedtime. Prescribed bronchodilators,

water, or saline may be neb-ulized and inhaled before postural drainage to

dilate the bron-chioles, reduce bronchospasm, decrease the thickness of mucus

and sputum, and combat edema of the bronchial walls. The rec-ommended sequence

of positioning is as follows: positions to drain the lower lobes first, then

positions to drain the upper lobes.

The

nurse makes the patient as comfortable as possible in each position and

provides an emesis basin, sputum cup, and paper tis-sues. The nurse instructs

the patient to remain in each position for 10 to 15 minutes and to breathe in

slowly through the nose and then breathe out slowly through pursed lips to help

keep the air-ways open so that secretions can drain while in each position. If

a position cannot be tolerated, the nurse helps the patient to assume a

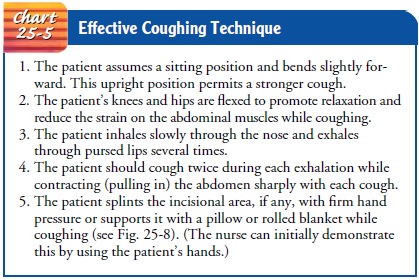

modified position. When the patient changes position, the nurse explains how to

cough and remove secretions (Chart 25-5).

If the patient cannot cough, the nurse may need to suction the secretions mechanically. It also may be necessary to use chest per-cussion and vibration to loosen bronchial secretions and mucus plugs that adhere to the bronchioles and bronchi and to propel sputum in the direction of gravity drainage (see “Chest Percus-sion and Vibration,” below). If suctioning is required at home, the nurse instructs caregivers in safe suctioning technique and care of the suctioning equipment.

After

the procedure, the nurse notes the amount, color, vis-cosity, and character of

the expelled sputum. It is important to evaluate the patient’s skin color and

pulse the first few times the procedure is performed. It may be necessary to

administer oxy-gen during postural drainage.

If

the sputum is foul-smelling, it is important to perform pos-tural drainage in a

room away from other patients and/or family members and to use deodorizers

unless contraindicated. Deodor-izers delivered in aerosol sprays can cause

bronchospasm and irri-tation to the patient with a respiratory disorder and

should be used cautiously (Zang & Allender, 1999). After the procedure, the

pa-tient may find it refreshing to brush the teeth and use a mouth-wash before

resting.

Chest Percussion and Vibration

Thick

secretions that are difficult to cough up may be loosened by tapping

(percussing) and vibrating the chest. Chest percussion and vibration help to

dislodge mucus adhering to the bronchioles and bronchi.

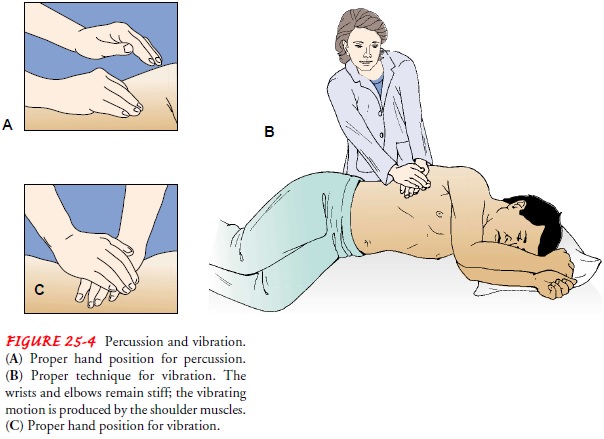

Percussion

is carried out by cupping the hands and lightly strik-ing the chest wall in a

rhythmic fashion over the lung segment to be drained. The wrists are

alternately flexed and extended so that the chest is cupped or clapped in a

painless manner (Fig. 25-4). A soft cloth or towel may be placed over the

segment of the chest that is being cupped to prevent skin irritation and

redness from direct contact. Percussion, alternating with vibration, is

performed for 3 to 5 minutes for each position. The patient uses diaphrag-matic

breathing during this procedure to promote relaxation (see “Breathing

Retraining,” below). As a precaution, percussion over chest drainage tubes, the

sternum, spine, liver, kidneys, spleen, or breasts (in women) is avoided.

Percussion is performed cautiously in the elderly because of their increased

incidence of osteoporo-sis and risk of rib fracture.

Vibration

is the technique of applying manual compression and tremor to the chest wall

during the exhalation phase of res-piration (see Fig. 25-4). This helps to

increase the velocity of the air expired from the small airways, thus freeing

the mucus. After three or four vibrations, the patient is encouraged to cough,

using the abdominal muscles. (Contracting the abdominal muscles in-creases the

effectiveness of the cough.)

A

scheduled program of coughing and clearing sputum, to-gether with hydration,

reduces the amount of sputum in most pa-tients. The number of times the

percussion and vibration cycle is repeated depends on the patient’s tolerance

and clinical response. It is important to evaluate breath sounds before and

after the procedures.

Nursing Management

When

performing chest physiotherapy, the nurse ensures that the patient is

comfortable, is not wearing restrictive clothing, and has not just eaten. The uppermost

areas of the lung are treated first. The nurse gives medication for pain, as

prescribed, before per-cussion and vibration and splints any incision and

provides pil-lows for support as needed. The positions are varied, but focus is

placed on the affected areas. On completion of the treatment, the nurse assists

the patient to assume a comfortable position.

The nurse must stop treatment if any of the following occur: increased pain, increased shortness of breath, weakness, light-headedness, or hemoptysis. Therapy is indicated until the patient has normal respirations, can mobilize secretions, and has normal breath sounds, and when the chest x-ray findings are normal.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

Chest physiotherapy is frequentlyindicated at home for patients

with COPD, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis. The techniques are the same as

described above, but gravity drainage is achieved by placing the hips over a

box, a stack of magazines, or pillows (unless a hospital bed is available). The

nurse instructs the patient and family in the positions and techniques of

percussion and vibration so that therapy can be continued in the home. In

addition, the nurse instructs the pa-tient to maintain an adequate fluid intake

and air humidity to prevent secretions from becoming thick and tenacious. It

also is important to teach the patient to recognize early signs of infec-tion,

such as fever and a change in the color or character of spu-tum. Resting 5 to

10 minutes in each postural drainage position before chest physiotherapy

maximizes the amount of secretions obtained.

Continuing Care.

Chest

physical therapy may be carried out dur-ing visits by a home care nurse. The

nurse also assesses the pa-tient’s physical status, understanding of the

treatment plan, and compliance with recommended therapy, as well as the

effective-ness of therapy. It is important to reinforce patient and family

teaching during these visits. The nurse reports to the patient’s physician any

deterioration in the patient’s physical status and in-ability to clear

secretions.

Breathing Retraining

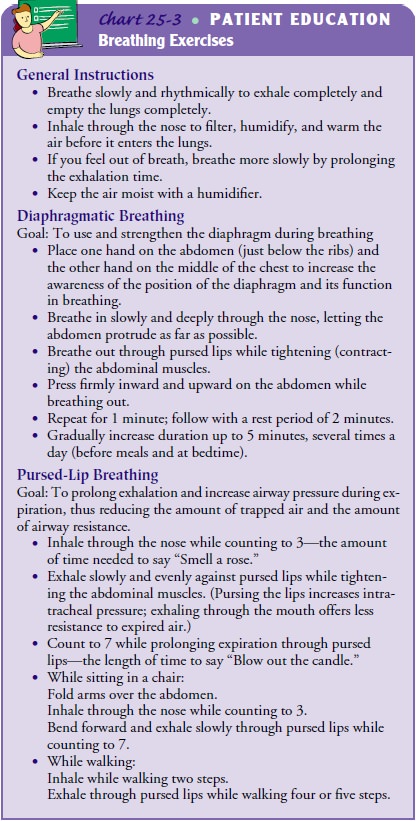

Breathing

retraining consists of exercises and breathing practices designed to achieve

more efficient and controlled ventilation and to decrease the work of

breathing. Breathing retraining is espe-cially indicated in patients with COPD

and dyspnea. These ex-ercises promote maximal alveolar inflation and muscle

relaxation, relieve anxiety, eliminate ineffective, uncoordinated patterns of

respiratory muscle activity, slow the respiratory rate, and decrease the work

of breathing. Slow, relaxed, and rhythmic breathing also helps to control the

anxiety that occurs with dyspnea. Specific breathing exercises include

diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breath-ing (see Chart 25-3).

The

goal of diaphragmatic breathing is to use and strengthen the diaphragm during

breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing can become automatic with sufficient

practice and concentration. Pursed-lip breathing, which improves oxygen

transport, helps to induce a slow, deep breathing pattern and assists the

patient to control breathing, even during periods of stress. This type of

breathing helps prevent airway collapse secondary to loss of lung elasticity in

emphysema. The goal of pursed-lip breathing is to train the muscles of

expiration to prolong exhalation and increase airway pressure during

expiration, thus lessening the amount of airway trapping and resistance. The

nurse instructs the patient in diaphragmatic breathing and pursed-lip

breathing, as described earlier in Chart 25-3. Breathing exercises may be

practiced in sev-eral positions because air distribution and pulmonary

circulation vary with the position of the chest. Many patients require

addi-tional oxygen, using a low-flow method, while performing breath-ing

exercises. Emphysema-like changes in the lung occur as part of the natural

aging process of the lung; therefore, breathing ex-ercises are appropriate for

all elderly patients who are hospitalized and elderly patients in any setting

who are sedentary, even with-out primary lung disease.

Nursing Management

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

The nurse instructs the patient tobreathe slowly and rhythmically

in a relaxed manner and to ex-hale completely to empty the lungs. The patient

is instructed always to inhale through the nose because this filters,

humidifies, and warms the air. If short of breath, the patient should

concen-trate on breathing slowly and rhythmically. To avoid initiating a cycle

of increasing shortness of breath and panic, it is often help-ful to instruct

the patient to concentrate on prolonging the length of exhalation rather than

merely slowing the rate of breathing. Minimizing the amount of dust or particles

in the air and pro-viding adequate humidification may also make it easier for

the pa-tient to breathe. Strategies to decrease dust or particles in the air

include removing drapes or upholstered furniture, using air fil-ters, and

washing floors and dusting and vacuuming frequently.

The

nurse instructs the patient that an adequate dietary intake promotes gas

exchange and increases energy levels. It is important to provide adequate

nutrition without overfeeding patients. Nurses should teach patients to consume

small, frequent meals and snacks. Having ready-prepared meals and favorite

foods available helps encourage nutrient consumption. Gas-producing foods such

as beans, legumes, broccoli, cabbage, and Brussels sprouts should be avoided to

prevent gastric distress. Because many of these patients

lack

the energy to eat, they should be taught to rest before and after meals to

conserve energy (Lutz & Przytulski, 2001).

Related Topics