Chapter: Biology of Disease: Toxicology

Metals - Toxicology Poisons

METALS

The presence of certain metals in high concentrations may be

toxic to humans. To diagnose metal toxicity, three features have to be

identified, namely, a source of the toxic metal, the presence of signs and

symptoms typical of toxicity by that metal and increased concentrations of the

metal in the body tissues. Metals that are commonly screened for toxicity

include lithium, aluminum and the heavy metals lead, arsenic, cadmium and

mercury. Lithium is widely used therapeutically to treat patients with certain

psychiatric disorders. However, plasma concentrations of lithium in excess of

1.5 mmol dm–3 should be avoided and regular measurements of serum

lithium concentrations are important in monitoring therapy. Lithium toxicity is

associated with tremors, drowsiness, tinnitus, blurred vision, polyuria,

hypothyroidism and, in severe cases, renal failure and coma.

Acute poisoning with aluminum is extremely rare. Indeed,

aluminum compounds are used for their antacid properties. The dietary intake of

aluminum is 5 to 10 mg day–1 and this amount is removed completely

by the kidneys. Unfortunately, patients with renal failure are susceptible to

aluminum toxicity. They cannot remove the aluminum and, as the water used in

dialysis may contain aluminum that can enter the body through the dialysis

membrane, the metal can build up to toxic concentrations and cause

osteodystrophy and encephalopathy. Aluminum toxicity is diagnosed by determining

its concentration in plasma. Chronic toxicity occurs at concentrations above

only 3 Mmol dm–3 whereas 10 Mmol dm–3 can cause acute poisoning. The treatment is

aimed mainly at prevention. When aluminum poisoning does occur, then its

excretion may be enhanced using chelating agents such as desferrioxamine.

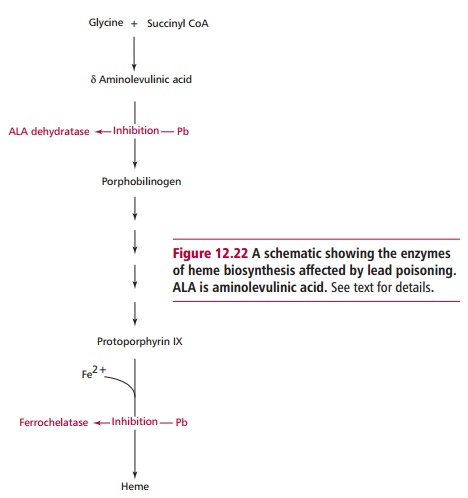

Lead is a heavy metal found in the environment. Common sources

include paints, old water pipes, petrol fumes, industrial pollution and

medication and cosmetics from the Indian subcontinent. Poisoning by lead can be

acute, which is rare, or, more commonly, chronic. It results from inhalation,

dermal absorption or ingestion, where it is actively absorbed by the GIT

through the calcium transport system. All tissues are affected by lead

poisoning although organ pathology is associated primarily with the nervous

system and the blood. In the blood, lead is concentrated in the erythrocytes

where it inhibits the activities of aminolevulinic acid (ALA) dehydratase and

ferrochelatase, enzymes involved in the synthesis of heme (Figure 12.22). Inhibition of ALA dehydratase is the most sensitive

measure of lead poisoning. Concentrations of lead in the blood in excess of

0.49 Mmol dm–3 are associated with illness in

children. If the concentration of lead increases above 3.4 Mmol dm–3,individuals

whose occupation exposes them to lead must be removed from its

source. Clinical features of lead poisoning include lethargy, abdominal

discomfort, anemia, constipation, encephalopathy and motor peripheral

neuropathy.

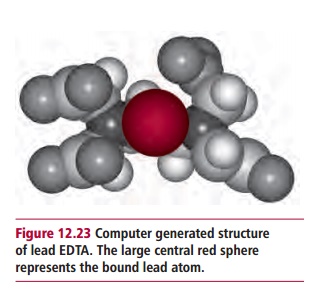

The management of patients with lead poisoning involves

identifying the lead source and removing the patients from it. Patients are

placed on chelating agents, such as EDTA (Figure

12.23) that is effective in both acute and chronic lead poisoning, but has

to be given intravenously. Another chelating agent, dimercaptosuccinic acid is

less efficient as a chelator but can be given orally.

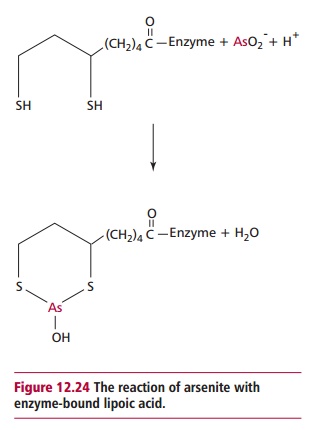

Chronic arsenic poisoning is associated with well water

contaminated with arsenical pesticides or, classically, with murder! Arsenic

occurs in a number of different forms, most of which are toxic although

arsenite (AsO2–) is much more

so than arsenate (HAsO4–). Arsenate

substitutes for Pi in biological systems, hence less ATP is produced.

Arsenite toxicity is associated with the formation of a stable complex with

enzyme-bound lipoic acids (Figure 12.24).

Indeed, arsenic poisoning can be explained by its ability to inhibit enzymes,

such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase and branched chain

α -oxoacid dehydrogenase, that require lipoic acid as

a coenzyme. Chronic poisoning with arsenic is usually associated with diarrhea,

polyneuropathy and dermatitis whereas acute poisoning with arsenic gives rise

to severe gastrointestinal pain, vomiting and shock. Poisoning can be diagnosed

by determining the concentration of arsenic in the hair or fingernails of the

victim. Values larger than 0.5 µg g–1 of hair indicate a significant

exposure to arsenic. The hair of a person chronically exposed to arsenic could

have 1000 times as much as this. Treatment of arsenic poisoning is aimed at

enhancing its excretion using chelating agents.

Chronic cadmium toxicity may occur in workers exposed to fumes

in cadmium-related industries, although concentrations of cadmium are twice as

high in tobacco smokers compared with nonsmokers. Concentrations in the serum

greater than 90 nmol dm–3 are associated with toxicity. Cadmium

poisoning causes influenza-like symptoms, such as chills, fever, muscular

aches, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. However, these symptoms

may resolve after a week provided there is no respiratory damage. More severe

exposures can cause bronchitis and pulmonary edema and occasionally

cardiovascular collapse. Long-term exposure may lead to nephrotoxicity with

proteinuria, bone disease and hepatotoxicity. The treatment of cadmium poisoning

usually involves removal from exposure. Treatment with chelating agents is not

effective because the soluble form of cadmium damages the kidney.

Mercury poisoning can be acute or chronic. It occurs following

exposure to mercury vapor, inorganic salts or organic compounds of mercury.

Mercury poisoning is primarily occupational but can be caused by contaminated

food. The clinical features of acute mercury poisoning include coughing,

bronchiolitis, pulmonary edema, pneumonitis, peripheral neuropathy and

neuropsychiatric problems. Chronic mercury poisoning causes anorexia, sweating,

insomnia, impaired memory, paresthesiae of the lips and extremities and renal

tubular damage. Mercury poisoning is usually diagnosed by determining the

concentration of mercury in serum and urine. Urine mercury/creatinine ratios

are often used to assess exposure. Ratios of 40 to 100 nmol mmol–1

require monitoring and further investigation, while values of greater than 100

nmol mmol–1 require the patient to be removed from the source of

mercury.

Acute mercury poisoning is treated with chelating agents such as

dimercaprol, to increase its excretion into bile and urine. Methylmercury is an

organic form of mercury that has been used to preserve seed grain.

Methylmercury poisoning can be caused by eating meat from animals which have

been fed treated seedgrain. An outbreak of mercury poisoning began in the 1950s

in Minamata bay in Japan and affected over 3000 villagers who ate fish

contaminated with methylmercury.

Related Topics