Chapter: Biology of Disease: Toxicology

Barbiturates - Toxicology Poisons

BARBITURATES

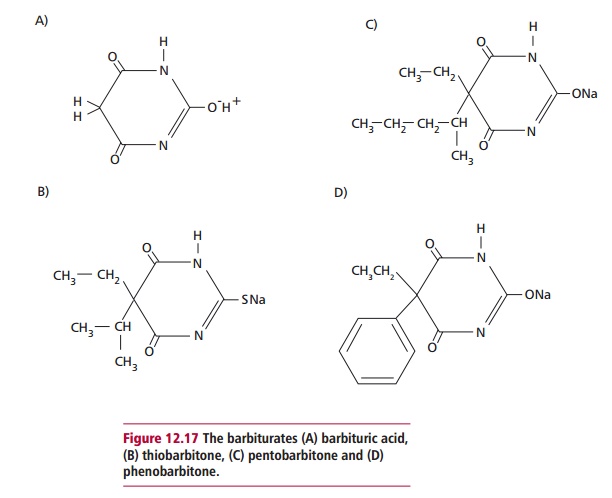

Barbiturates are a group of drugs based on the parent compound,

barbituric acid (Figure 12.17 (A)).

All are sedatives, that is, they depress certain activities of the CNS.

Although they have well-established therapeutic uses, barbiturates can be toxic

if taken as an overdose, indeed, they are one of the commonest methods for

attempting suicide. They were once used as recreational drugs, for example in

purple hearts, and this too led to accidental overdoses. Barbiturates have now

largely been replaced by benzodiazepines and barbiturate overdose is less

likely to be encountered today.

Barbiturates induce drug dependence and this involves three

distinct and independent components: tolerance, physical dependence and

compulsive abuse or psychic craving. Barbiturate dependence stimulates all

three components to such an extent that they produce major problems for the

individual user as well as for society at large. Once barbiturate dependence

has developed, abrupt withdrawal from the drug induces a particularly

unpleasant withdrawal syndrome. This is characterized by weakness, tremors,

anxiety, increased respiratory and pulse rates with a corresponding increased

blood pressure, vomiting, insomnia, loss of weight, convulsions of the grand

mal type and a psychosis resembling alcoholic delirium tremens. Thus during

withdrawal, it is appropriate to reduce the dosage gradually over an extended

period.

The length of time barbiturates act in vivo varies. Some, for example thiobarbitone (Figure 12.17 (B)), are short acting,

others, such as pentobarbitone (Figure

12.17 (C)), act in the medium term, while the group including the best

known barbiturate, phenobarbitone (Figure

12.17 (D)), induce long-lasting effects. Barbiturates act by enhancing the

effects of GABA by binding to a different site on the receptors on target

neurons of the CNS to those for GABA itself. The blood–brain barrier (Figure 3.4) prevents the easy entry of

many substances into the brain compared with their uptake into other tissues.

However, lipid-soluble substances, such as the barbiturate thiopentone, enter

the brain quickly by passive diffusion. This rapid uptake allows thiopentone to

exert its anesthetic effects extremely quickly. In contrast, other

barbiturates, such as phenobarbitone, are weak acids and so may be ionized.

This slows their entry into the CNS but produces a longer lasting effect. The

life-threatening effects of barbiturate poisoning include depression of the

centers in the CNS that control respiration and blood

circulation. Some barbiturates, for example phenobarbitone, can

also induce the synthesis of monooxygenase enzymes and so, by altering the rate

or route of metabolism of other drugs, can alter their toxicities.

There is no antidote for barbiturate poisoning. Primary care is

to maintain a free airway, administer artificial respiration if required and

forced alkaline diuresis. The pH dependence of ionization of many common

barbiturates is exploited by infusions of large volumes of sodium hydrogen

carbonate containing the osmotic diuretics urea or mannitol. This increases the

pH of plasma relative to the cytoplasm of cells and increases the proportion of

ionized barbiturate in the plasma causing more of the un-ionized drug to

diffuse out of the tissues, including the brain, into the plasma. This can

promote a diuresis as large as 12 dm3 in 24 h. The ionized form is

also excreted more rapidly since the alkalinity of the provisional urine

ensures it remains ionized and cannot cross the tubule wall back into the

plasma.

Related Topics