Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Shrimps and Prawns

Major cultivated species of shrimps and prawns

Major cultivated species of

shrimps and prawns

Attention has so far been directed to the culture of tropical and

sub-tropical species of shrimps, and the so-called giant fresh-water prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Spawning and

larval rearing of the kuruma shrimp in captivity in Japan in the 1950s aroused

considerable interest in intensive farming of shrimps and this species became

the focus of attention for a number of years. It was introduced in many

countries in Asia, southern Europe, West Africa, the southern USA and Central

and South America. Very soon, attention turned to some of the larger local

species of shrimps, which were better adapted to prevailing temperature

conditions, and the larvae and juveniles of which were readily available to

supplement inadequate production from hatcheries. In Asia, the more important

species are the tiger shrimp P. monodon

and the Indian or white shrimp P. indicus.

The banana shrimp P.merguiensis, the

green tiger or bear shrimp P.

semisulcatus and the oriental shrimp

P. orientalis (= chinensis) are

also of commercial interest in some countries of the region. The redtailed

shrimp P. penicillatus is a species

cultured in Taiwan. Metapenaeus monoceros,

M.brevicornis and M. ensis form subsidiary speciesin shrimp farms in several Asian

countries.

Besides the imported P. japonicus,

the main interest in the Mediterranean countries of Europe has been in the

local Mediterranean shrimp (triple-grooved shrimp) P. kerathurus.

Present efforts in establishing shrimp farming in Africa have mainly involved the culture of P. indicus on the East Coast and

P. notialis onthe West Coast. The most important species in Central and

South America are the white-leg shrimp or camaron langostino P. vannamei and the blue shrimp P. stylirostris. Besides the blue

shrimp, there are at least four species that have reached commercial-level

culture in the countries bordering the Atlantic Coast of Central and South

America, namely the brown shrimp

As well as these, production on an experimental scale has been

undertaken for the southern white shrimp P.

schmitti. Though all the above species are of potential importance in

commercial shrimp farming, and several others are being investigated for their

suitability, the bulk of the present production comes from P. monodon, P. chinensis,

P. vannamei, P. merguiensis, P. japonicus and P. indicus. Production estimates for

crustaceans for the year 2000 totalled 1.647 million tons. Production of P. monodon was the highest (571000

tons), followed P. chinensis (219000

tons) and P. vannamei (144000 tons)

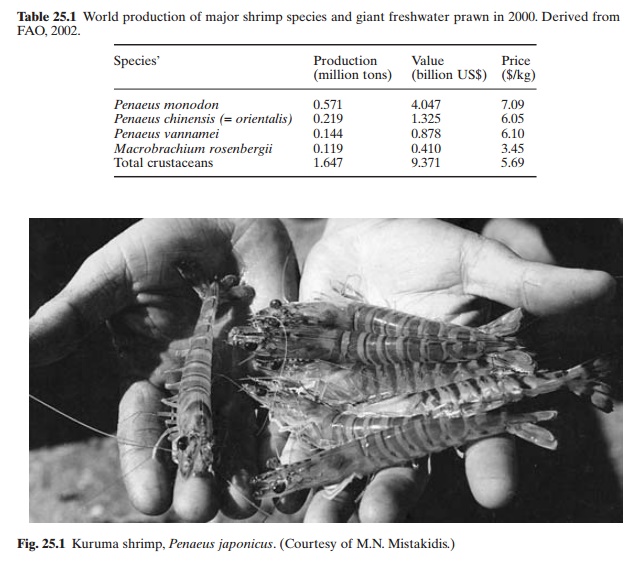

(see Table 25.1).

Much of the research effort on shrimp culture has been concentrated on

the development of hatchery techniques for controlled spawning and larval

rearing, as in the case of other marine aquaculture species. In the early years

of investigations, considerable problems were faced in rearing and feeding the

hatchlings through the different stages of development and obtaining reasonable

survival rates.

The search for species that may be easier to reproduce and have a

shorter larval history resulted in investigations on the giant fresh-water

prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii. The

success achieved in the mass production of post-larvae of this species in the

1970s led to widespread interest in its culture, and it has been imported into

an impressive number of countries in the tropical, sub-tropical and even

temperate climates, in almost every continent.

World production of M. rosenbergii

increased from 26588 tons in 1991 to 118501 tons in 2000 (FAO, 2002). China,

which is the world’s lead producer now, produced 97420 tons in 2000, accounting

for 8 per cent of would production. But China began freshwater prawn culture

only in 1996, even though Taiwan(China) with a production of 16196 tons was the

lead producer in 1991. Thailand is the other major player in prawn culture but

its annual production, which peaked at 10305 tons in 1992, had come down to

3700 tons in 2000, apparently owing to the Thai preference for marine shrimp

farming, which is due in part to the easier technology in breeding and rearing

and consumer preference for the shrimp.

The oriental river prawn (M.

nipponense), though small in size (8–9cm), is being cultured extensively in

China as it can stand the winter temperatures and can be bred exclusively in

freshwater, unlike M. rosenbergii.

The estimate of annual farmed production of M.

nipponense in China was 15000 tons in 1998 (Wang and Qianhong, 1999). M. nipponense is more popular

particularly in Jiangsu province where about 40000ha were under production. The

production of M. nipponense has

increased further recently (Kutty et al.,

2000).

In addition to M. nipponense,

which is now under substantial commercial culture, the most serious contenders

for reaching commercial status are M.

malcolmsonii in the Indian sub-continent, Cinnamon river prawn (M. acanthu-rus) and M. carcinus in Central America, and M. amazonicum in South America (Kanaujia et al., 1997; Herman et al.,

1999; Kutty et al.,2000).

Though there are considerable similarities in the culture technologies

for the various species, there are also a number of differences brought about

by environmental requirements, breeding and feeding behaviour, and

compatibility with other species. Within the general requirements of water

salinity (10–40ppt), temperature tolerance (18–33°C), the character of soil

substrates in the culture facilities, feed quality and response to high-density

culture, Penaeid shrimps have specific requirements and limitations. Growth

rates and harvest sizes (based on the commercial size of 10–45g weight) also

vary considerably.These factors greatly influence the compatibility of

different species of Penaeids in polyculture, but can be advantageously used in

rotational production of different species in the same facility, in accordance

with seasonal changes of salinity and temperature. In temperate climates,

different species can be used for culture in summer and winter. In tropical

monsoon areas subject to marked changes of

salinity, the production of a species preferring low salinity can be

alternated with one that requires high-salinity water. The short duration of

culture periods makes such rotation very feasible in many areas.

The fresh-water prawn M.

rosenbergii is commercially important because of its size, as well as its eating

qualities.The males can attain a size of about 25cm and the females about 15cm.

Though adults are found in fresh- and brackish-water areas, the species

requires water of about 12ppt salinity for larval rearing. This requirement has

created problems in siting hatcheries near grow-out facilities, but it has now

been shown that this can be overcome by the use of sea water or brine trucked

in from the nearest

source, as performed by operators of small back-yard hatcheries in

Thailand, or by the use of artificial sea water as in a commercial farm in

Zimbabwe. The adults are omnivorous and feed on a variety of foods of animal

and vegetable origin.

Among the species so far studied, P.

japonicus (fig. 25.1). P. orientalis and P. setiferus areconsidered to be most

suited for production in temperate climates. Penaeus japonicus is cultured in Japan, Taiwan and in a less

intensive way in Brazil, France, Spain and Italy. Penaeusorientalis is cultured in Korea and China. Penaeus setiferus is the species of

interest in thetemperate regions of the USA. Much of the available knowledge on

modern shrimp culture

originated with intensive studies on P.

japonicus. It is a hardy species, but cannot tolerate lowsalinity or high

temperatures. It requires diets containing about 60 per cent protein for

satisfactory growth and grow-out ponds or tanks should have a sandy bottom.

The tiger shrimp P. monodon

(fig. 25.2), is the fastest growing species used in aquaculture in Asia. The

species is euryhaline and can tolerate almost fresh-water conditions, even

though 10–25ppt is considered optimum. It cannot tolerate temperatures below

12°C and the upper limit of tolerance is around 37.5°C.

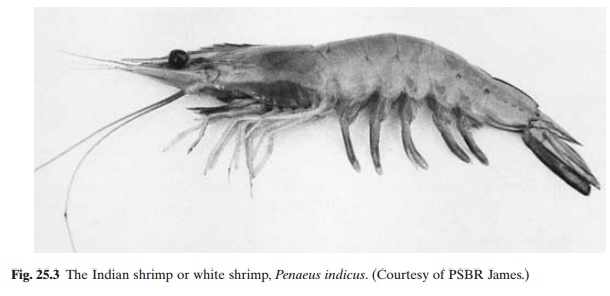

Penaeus indicus and P. merguiensis (figs

25.3and 25.4) have very similar habits in many respects, but in aquaculture the

former species exhibits a preference for sandy substrates and the latter for

muddy ones. Both species require high salinities (20–30ppt) for good growth and

cannot tolerate salinities outside the range 5– 40ppt. The lethal temperature

is above 34°C. Under the current pond management systems,

The three Metapenaeid species, M.

monoceros, M. brevicornis and M. ensis, are easier toculture, as they

mature readily in captivity and their larval culture presents fewer problems.

Metapenaeus monoceros and M. brevicornis areknown to

breed in ponds. They are tolerant of low salinities and high temperatures and

can therefore be cultured in a wider variety of sites. Harvestable size is

attained in a shorter time of two to three months, and survival rates are high.

But their final size is smaller, generally about 14cm for M. monoceros and M. ensis

and 7.5– 12.5cm for M. brevicornis.

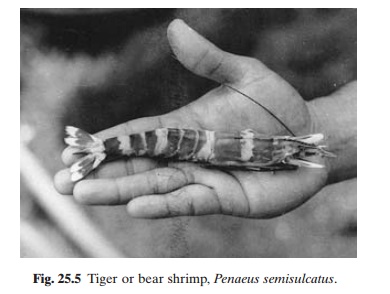

Penaeus semisulcatus (fig. 25.5) grows to alarge size and fetches a good price in the markets

in Asia and the Middle East, but it requires high salinities and its growth in

ponds is slow. Though easy to propagate, survival rates in grow-out facilities

are reported to be very

low. Among the shrimps cultured in Central and South America, P. vannamei (fig. 25.6) is highly

euryhaline and can withstand salinities ranging from 0 to 50ppt and

temperatures ranging from 22 to 32°C. Low salinities and warmer temperatures

are characteristic of the rainy season (December to April) in countries like

Ecuador and higher salinities and cooler temperatures prevail during the

remaining months. This partly accounts for the higher survival rate of P. vannamei compared to P.stylirostris, and its preference in

pond farmingin these countries.

Related Topics