Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Listening: The Key Skill in Psychiatry

Listening:

The Key Skill in Psychiatry

It was Freud who raised the psychiatric technique

of examination – listening – to a level of expertise unexplored in earlier

eras. As Binswanger (1963) has said of the period prior to Freudian influ-ence:

psychiatric “auscultation” and “percussion” of the patient was performed as if

through the patient’s shirt with so much of his essence remaining covered or

muffled that layers of meaning remained unpeeled away or unexamined.

This metaphor and parallel to the cardiac

examination is one worth considering as we first ask if listening will remain

as central a part of psychiatric examination as in the past. The explosion of

biomedical knowledge has radically altered our evolving view and practice of

the doctor–patient relationship. Physicians of an earlier generation were

taught that the diagnosis is made at the bedside – that is, the history and

physical exami-nation are paramount. Laboratory and imaging (radiological, in

those days) examinations were seen as confirmatory exercises. However, as our

technologies have blossomed, the bedside and/or consultation room examinations

have evolved into the method whereby the physician determines what tests to

run, and the tests are often viewed as making the diagnosis. A cardiologist

colleague expresses the opinion that, given the growing availability of

non-invasive tests – echocardiograms, for example – he is not sure this is a

bad thing (Hillis, 2001, personal communication).

So can one imagine a time in the not-too-distant

future when the psychiatrist’s task will be to identify that the patient is

psychotic and then order some benign brain imaging study which will identify

the patient’s exact disorder?

Perhaps so, but will that obviate the need for the

psychiatrist’s special kind of listening? Indeed, there are those who claim

that psychiatrists should no longer be considered experts in the doctor–

patient relationship (where expertise is derived from their unique training in

listening skills) but experts in the brain (Nestler, 1999, personal

communication). As we come truly to understand the relationship between brain

states and subtle cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal states, one could

also ask if this is a distinction that really makes a difference. On the other

hand, the psychiatrist will always be charged with finding a way to relate

effectively to those who cannot effectively relate to themselves or to oth-ers.

There is something in the treatment of individuals whose illnesses express

themselves through disturbances of thinking, feeling, perceiving and behaving

that will always demand special expertise in establishing a therapeutic

relationship – and that is dependent on special expertise in listening.

Traditionally, this kind of listening has been

called “listening with the third ear” (Reik, 1954). Other efforts to label this

difficult-to-describe process have developed other terms: the interpretive

stance, interpersonal sensitivity, the narrative perspective (McHugh and

Slavney, 1986). All psychiatrists, regardless of theoretical stance, must learn

this skill and struggle with how it is to be defined and taught. The biological

or phenomenological psychiatrist listens for subtle expressions of

symptomatology; the cognitive–behav-ioral psychiatrist listens for hidden

distortions, irrational assump-tions, or global inferences; the psychodynamic

psychiatrist listens for hints at unconscious conflicts; the behaviorist

listens for covert patterns of anxiety and stimulus associations; the family

systems psychiatrist listens for hidden family myths and structures.

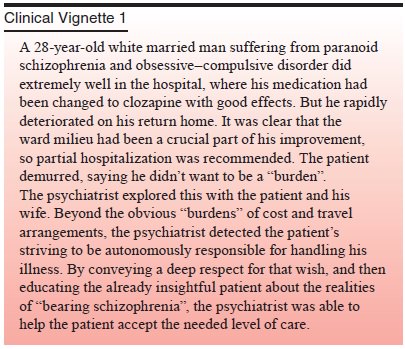

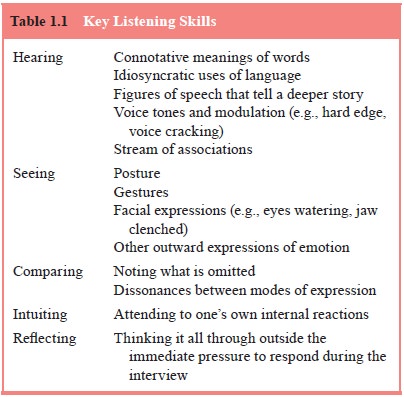

This requires sensitivity to the storyteller, which

integrates a patient orientation complementing a disease orientation. The

listener’s intent is to uncover what is wrong and to put a label on it. At the

same time, the listener is on a journey to discover who the patient is,

employing tools of asking, looking, testing and clar-ifying. The patient is

invited to collaborate as an active informer. Listening work takes time,

concentration, imagination, a sense of humor, and an attitude that places the

patient as the hero of his or her own life story. Key listening skills are

listed in Table 1.1.

The enduring art of psychiatry involves guiding the

de-pressed patient, for example, to tell his or her story of loss in addi-tion

to having him or her name, describe, and quantify symptoms

of depression. The listener, in hearing the story,

experiences the world and the patient from the patient’s point of view and

helps carry the burden of loss, lightening and transforming the load. In

hearing the sufferer, the depression itself is lifted and relieved. The

listening is healing as well as diagnostic. If done well, the listener becomes

a better disease diagnostician. The best listen-ers hear both the patient and

the disease clearly, and regard every encounter as potentially therapeutic.

Related Topics