Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Theoretical Perspectives on Listening

Theoretical

Perspectives on Listening

Listening is the effort or work of placing the

therapist where the patient is (“lives”). Greenson (1978) would call it “going

along with”; Rogers (1951) “centering on the client”. The ear of the empathic

listener is the organ of receptivity – gratifying and, at times, indulging the

patient. Greenson would say that it is better to be deceived going along with

the patient than to reject him/her prematurely and have the door slammed to the

patient’s inner world. That is what is meant by the suspension of beliefs for

the discovery of the true self. Harry Stack Sullivan, the father of

in-terpersonal psychiatry, would remind us to heed those shrewd, small questions:

“What is he up to?” “Where is he taking us?” Every human being has a preferred

interpersonal stance, a set of relationships and transactions with which she or

he is most comfortable and feels most gratified. The problem is that for most

psychiatric patients they do not work well. This is the wisdom that Sullivan

(1953) was articulating.

Beyond attitudes that enable or prevent listening

there is a role for specific knowledge. It is important to achieve the

cog-nitive structure or theoretical framework and use it with rigor and

discipline in the service of patients so that psychiatrists can employ more

than global “feelings” or “hunches”. In striving to grasp the inner experience

of any other human being, one must know what it is to be human; one must have an

idea of what is inside any person. This provides a framework for understand-ing

what the patient – who would not be a patient if he fully understood what was

inside of him – is struggling to communi-cate. Personality theory is absolutely

crucial to this process.

Whether we acknowledge it or not, every one of us

has a theory of human personality (in this day and age of porous boundaries

between psychology and biology, we should really speak of a psychobiological

theory of human experience) which we apply in various situations, social or

clinical. These theories become part of the template alluded to earlier that

allow certain words, stories, actions, and cues from the patient to jump out

with profound meaning to the psychiatrist. There is no substitute for a

thorough knowledge of many theories of human functioning and a well disciplined

synthesis and internal set of rules to decide which theories to use in which

situations.

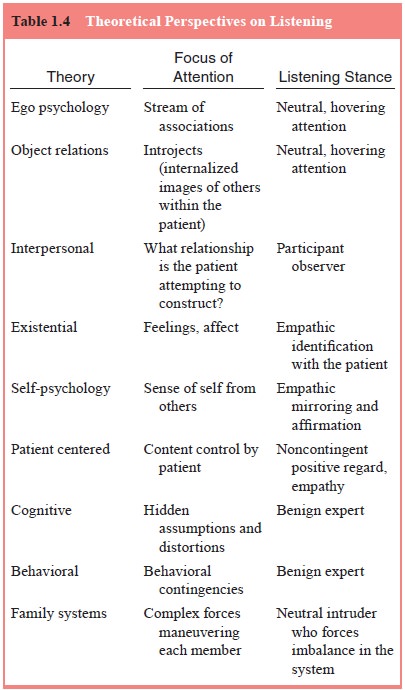

Different theoretical positions offer slightly

different and often complementary perspectives on listening (Table 1.4). The

basic tools of therapeutic power and diagnostic acumen spring from the

following:

· Freud’s

associative methods (Brill, 1938) and ego psychology (Freud, 1946), in which

one listens for the associative trends and conflicts.

·

Melanie Klein’s (1975) and Harry Stack Sullivan’s

(1953) ob-ject relations theory. The former discovered the story through inner

world exploration and recognized the introjected

persons of the past who live within the patient’s mind,

com-prising the person’s psychic structure; the latter discovered the knowing

through the interpersonal experience of the ther-apeutic dyad (Greenberg and

Mitchell, 1983).

· Binswanger’s

(1963) understanding of the condition of empa-thy, in which the listener gives

up his or her own position for that of the storyteller.

· Kohut’s

(1991) self-psychology, which emphasizes the use of vicarious introspection to

reflect (mirror) back to the patient what is being understood. This mirroring

engenders in the storyteller a special sense of being “found”, that is, of

being known, recognized, affirmed, and heard. This feeling of be-ing heard

helps to undo the sense of aloneness so common in psychiatric patients.

Each of the great schools of psychotherapy places

the psy-chiatrist in a somewhat different relationship to the patient. This may

even be reflected in the physical placement of the therapist in relation to the

patient. In a classical psychoanalytic stance, the therapist, traditionally

unseen behind the patient, assumes an ac-tive, hovering attention. Existential

analysts seek to experience the patient’s position and place themselves close

to and facing the patient. The interpersonal psychiatrist stresses a

collaborative dialogue with shared control. One can almost imagine the two side

by side as the clinician strives to sense what the storyteller is doing to and

with the listener. Interpersonal theory stresses the need for each participant

to act within that interpersonal social field.

In the object relations stance, the listener keeps

in mind the “other people in the room” with him and the storyteller, that is,

the patient’s introjects who are constantly part of the internal conversation

of the patient and thus influence the dialogue within the therapeutic dyad. In

connecting with the patient, the listener is also tuned in to the fact that

parts and fragments of him or her are being internalized by the patient. The

listener becomes another person in the room of the patient’s life experience,

within and outside the therapeutic hour. Cognitive and behavioral

psy-chiatrists are kindly experts, listening attentively and subtly for hidden

assumptions, distortions, and connections. The family systems psychiatrist sits

midway among the pressures and forces emanating from each individual, seeking

to affect the system so that all must adapt differently.

we can see the different theoretical models of the

listening process in the dis-covery of the meaning of “little fella”. Freud’s

model is that the psychiatrist had listened repeatedly to a specific

association and inquired of its meaning. Object relations theorists would note

that the clinician had discovered a previously unidentified, powerful introject

within the therapeutic dyad. The interpersonal psychia-trist would see the

shared exploration of this idiosyncratic man-ner of describing one’s youth; the

patient had been continually trying to take the therapist to “The Andy Griffith

Show”. That is, the patient was attempting to induce the clinician to share the

experience of imagining and fantasizing about having Andy Griffith as a father.

Existentialists would note how the psychiatrist was

changed dramatically by the patient’s repeated use of this phrase and then

altered even more profoundly by the memory of Andy Griffith, “the consummate

good father” in the patient’s words. The therapist could never see the patient

in quite the same way again, and the patient sensed it immediately. And Kohut

wouldnote the mirroring quality of the psychiatrist’s interpreting the meaning

of this important memory. This would be mirroring at its most powerful,

affirming the patient’s important differences from his family, helping him to

consolidate the memories. The behavioral psychiatrist would note the reciprocal

inhibition that had gone on, with Andy Griffith soothing the phobic anxieties

in a brutal family.

A cognitive psychiatrist would wonder whether the

pa-tient’s depression resulted from a hidden assumption that any-thing less

than the idyllic images of television was not good enough. The family systems

psychiatrist would help the patient see that he had manipulated the forces at

work on him and actu-ally changed the definition of his family.

The ways and tools of listening also change,

according to the purpose, the nature of the therapeutic dyad. The ways of

listening also change depending upon whether or not the psy-chiatrist is

preoccupied or inattentive. The medical model psy-chiatrist listens for signs

and symptoms. The analyst listens for the truth often clothed in fantasy and metaphor.

The existentialist listens for feeling, and the interpersonal theorist listens

for the shared experiences engendered by the interaction. Regardless of the

theoretical stance and regardless of the mental tension be-tween the medical

model’s need to know symptoms and signs and the humanistic psychiatrist’s

listening to know the sufferer, the essence of therapeutic listening is the

suspension of judgment be-fore any presentation of the story and the

storyteller. The listener is asked to clarify and classify the inner world of

the storyteller at the same time he is experiencing it – no small feat!

Related Topics