Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Growing and Maturing as a Listener

Growing and

Maturing as a Listener

Transference/countertransference influence not only

relation-ships in traditional psychotherapy but also interactions be-tween all

physicians and patients and is always present as a filter or reverberator to

that which is heard. However, even the most experienced of listeners are not

always aware of the ways in which their patients’ stories are impacted by

countertrans-ference. Patients come, too, with tendencies and predisposi-tions

to experience the listener, the other person in the thera-peutic dyad, in

familiar but distorted fashion. The patient may idealize and adapt to

interpretations. She/he may be hostile and distrustful, identifying the

psychiatrist in an unconscious way with one who has been rejecting in the past.

Listening to the “flow of consciousness”, the psychiatrist discerns a thread of

continuity and purposefulness in the patient’s communica-tions. As the

psychiatrist becomes more and more familiar with his patient, he will discover

the connections between threads and the meaning will become apparent. This

awareness may come as a sign and symptom, fantasy, feeling, or fact.

There is an increasing recognition that to be a

healing listener one must be able to bear the burden of hearing what is told.

Like the patient, we fear what might be said. A patient’s story may be one of

rage in response to early childhood attach-ment ruptures or abuse, of sadness

as losses are remembered, or of terror in response to disorganization during

the experience of perceptual abnormalities accompanying psychotic breaks. The

patient’s stories invariably invoke anger, shame, guilt, ab-ject helplessness,

or sexual feelings within the listener. These feelings, unless attended to,

appreciated and understood will block the listening that is essential for

healing to take place.

Every insight is colored by what the listener has

known. It is impossible to know that which is not experienced. The

psy-chiatrist comes with his own experiences and the experiences he has had

with others. To listen in the manner we are describ-ing here is another way of

truly experiencing the world. The experiences include the imaginings of how it

must be to be 87 years old as a patient when one is a 35-year-old doctor just

fin-ishing residency; to be female when one is male; to be a child again; to

grow up African-American in a small white suburb of a large city; to be an

immigrant in a new country; to be Middle Eastern when one is Western European,

and so on. One comes to know by listening with imagination, allowing the words

of the patient to resonate with one’s own experiences or with what one has come

to know through hearing with imagination the stories of other patients or

listening to the thoughts or insights of supervisors.

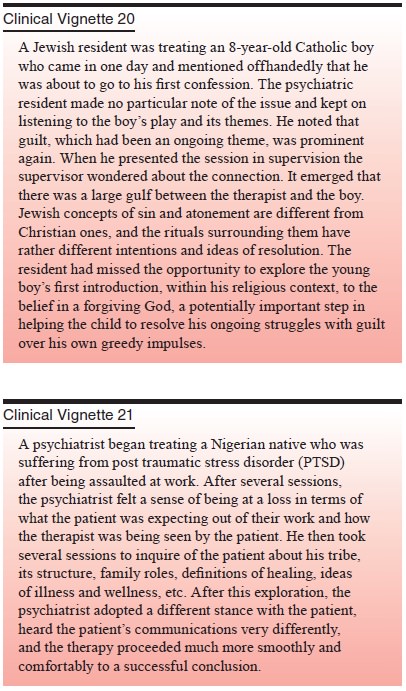

The best psychiatrists continue all their

professional lives to learn how to listen better. This may be thought of not

only as a matter of mastering countertransference but of self-education. One

must learn to recognize when there are impasses in the treat-ment and to seek

education, from a colleague or, perhaps, even from the patient. Consider these

two examples.

How can the psychiatrist’s demeanor convey to the

patient that he is safe to tell his story, that the listener is one who can be

trusted to be with him, to worry with him, and serve as a helper? Much is

written about the demeanor of the psychiatrist. The air, deportment, manner, or

bearing is one of quiet anticipation – to receive that which the patient has

come to tell and share in the telling. Signals of anticipation and curiosity

may be conveyed by such statements as “I’ve thought about what you said last

time,” “How do you feel about…?” “What if…?”

Efforts of clarification often serve as bridges

between ses-sions and communicate that the listener is committed to a fuller

understanding of the patient. Patients have the need to experience the

psychiatrist as empathic. Empathy describes the feeling one has in hearing a

story which causes one to conjure up or imagine how it would have been to have

actually have had an experience oneself. How does one integrate all this so

that it is automatic but not deadened by automaticity? How does the

psychiatrist con-tinue to hear the “same old thing” with freshness and renewal?

How does one encourage the patient with consistency, clarity, and assurance in

the face of uncertainty and occasional confusion? Not by assurance that

everything will be all right when things might probably not be. Not by

attempting to talk the patient into seeing things the clinician’s way but rather

by the psychiatrist’s having the capacity to hear things his patient’s way,

from the pa-tient’s perspective.

Psychiatry is one of those rare disciplines where

the expe-rience of listening over and over again allows the listener to grow in

their capacities to hear and to heal. Hopefully, we get better and better as

the years advance, become smoother, and develop a style which blends with our

personality and training. We are renewed by the shared experiences with our

patients.

To hear stories of the human condition reminds the

psychi-atrist that he, too, is human. There is time to make discoveries in the

patient’s stories from previous times, and maybe in previous patients. Patients

will always endeavor to tell their stories. The psychiatrist continues to grow

by being the perpetual student, always with the ear for the lesson, the

remarkable life stories of his patients.

Related Topics