Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Listening as More Than Hearing

Listening as

More Than Hearing

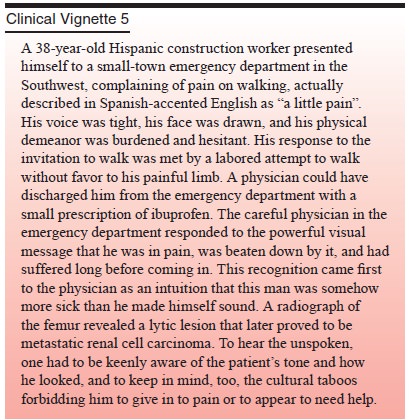

Listening and hearing are often equated in many

people’s minds. However, listening involves not only hearing and understand-ing

the speaker’s words, but attending to inflection, metaphor, imagery, sequence

of associations and interesting linguistic selections. It also involves seeing

– movement, gestures, facial expressions, subtle changes in these – and

constantly compar-ing what is said with what is seen, looking for dissonances,

and comparing what is being said and seen with what was previously communicated

and observed. Further, it is essential to be aware of what might have been said

but was not, or how things might have been expressed but were not. This is

where clues to idiosyncratic meanings and associations are often discovered.

Sometimes, the most important meanings are embedded in what is conspicuous by

its absence.

It was Darwin (1955) who first observed that there

appears to be a biogrammar of primary emotions that all humans share and

express in predictable, fixed action patterns. The mean-ing of a smile or nod

of the head is universal across disparate cultures. This insight was lost until

the late 1960s when several researchers from different fields (Tiger and Fox,

1971; Tomkins and McCarter, 1964) returned to it and demonstrated empirically

the cross-cultural consistency of emotional expression. LeDoux (1996) has been

a leader in identifying the neurobiological sub-strate for these primary

emotions. Leslie Brothers (1989), using this work and her own experiments with

primates, developed a hypothesis about the biology of empathy based on seeing

as well as hearing. Both she and Damasio (1994) have identified the amy-gdala

and the inferior temporal lobe gyrus as the neurobiologicalsubstrate for

recognition of and empathy for others and their emotional states. Further research

has identified that these parts of the brain are, on the one hand, prededicated

to recognizing certain gestures, facial expressions, and so on, but require

effec-tive maternal–infant interaction in order to do so (Schore, 2001). The

“gleam in the mother’s eye” of Mahler and colleagues (1975) is literally

translated into the reflection of the mother’s fovea as she gazes at her

infant, stimulating the nondominant orbital fron-tal cortex which, in turn,

completes the key temporal circuits.

All of this is synthesized in the listener as a

“sense” or intuition as to what the speaker is saying at multiple levels. The

availability of useful cognitive templates and theories enables the listener to

articulate what is heard.

As has been implied, not only must one

affirmatively “hear” all that a patient is communicating, one must overcome a

variety of potential blocks to effective listening.

Related Topics