Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

To Be Found: The Psychological Product of Being Heard

To Be Found:

The Psychological Product of Being Heard

Psychiatric patients may be lonely, isolated,

demoralized, and desperate, regardless of the specific diagnosis. They have lost

themselves and their primary relationships, if they ever had any. Stanley

Jackson (1992) makes the point that before anything else can happen, they must

be found, and feel found. They can only be found within the context of their

own specific histories, cultures, religions, genders, social contexts, and so

on. There is nothing more healing than that experience of being found by

another. The earliest expression of this need is in infancy and we refer to it

as the need for attachment. Referring to middle childhood, Harry Stack Sullivan

spoke of the importance of the pal or buddy. Kohut spoke of the lifelong need

for self-objects. In lay terms, it

is of-ten subsumed under the need for love, security, and acceptance.

Psychiatric patients have lost or never had this experience. How-ever obnoxious

or destructive or desperate their overt behavior, it is the psychiatrist’s job

to seek and find the patient. That is the purpose of listening.

If we look back, wherein the phrase “little fella”

bespoke such deep and important unverbalized meaning, the patient’s reaction to

the memory and recognition by the psychiatrist was dramatic. He had always

known he was dif-ferent in some indefinable ways from his family. That

difference had been both a source of pride and pain to him at various

devel-opmental stages. However, the recognition of the specific source, its

meaning, and its constant presence in his life created a whole new sense of

himself. He had been found by his psychiatrist, who echoed the discovery, and

he had found an entire piece of himself that he had enacted for years, yet

which had been disconnected from any integrated sense of himself.

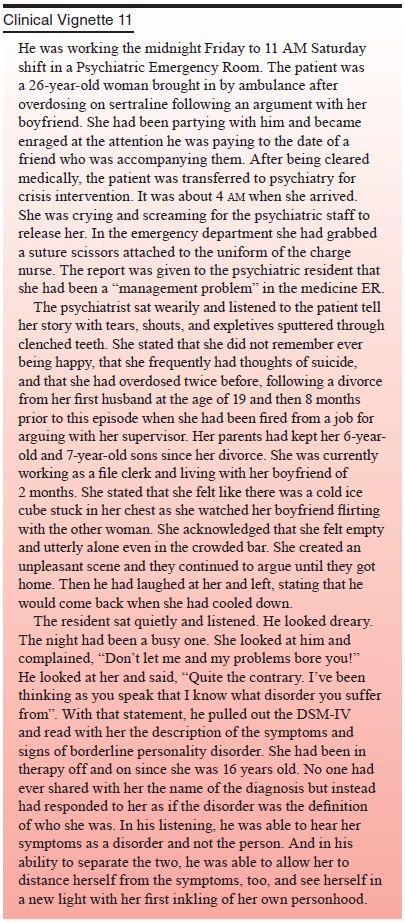

Sometimes objectifying and defining the

disease/disorder enables the person to feel found. One of the most challenging

patients to hear and experience is the acting out, self-destructive, demanding

person with borderline personality disorder. Even as the prior sentence

conveys, psychiatrists often experience the di-agnosis as who the patient is

rather than what she suffers. The following case conveys how one third year

resident was able to hear such a patient, and in his listening to her introduce

the idea that the symptoms were not her but her disorder.

Gender can play a significant role in the

experience of feel-ing found. Some individuals feel that it is easier to

connect with a person of the same sex; others, with someone of the opposite

sex. Psychiatrists vary in their sensitivity to the different sexes. Some may

do better with those who have cho-sen more traditional roles; others may be

more sensitive to those who have adopted more modern roles.

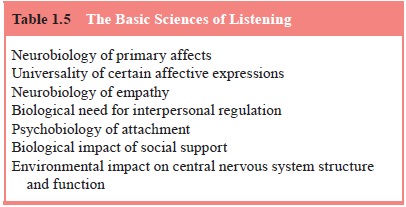

We now know that just as there is a neurobiological

basis for empathy and countertransference, there is a similar biologi-cal basis

for the power of listening to heal, to lift psychological burdens, to

remoralize and to provide emotional regulation to patients who feel out of

control in their rage, despair, terror, or other feelings (Table 1.5).

Attachment and social support are psy-chobiological processes that provide the

necessary physiological regulation to human beings. This has been shown by the

work of Hofer (1996), Cobb (1976), Meaney (2001), Nemeroff (Heim and Nemeroff,

2001), and many others. Additional work of Paul

Ekman (1992) supports the notion of the patient’s

capacity to perceive empathy through the powerful nonverbal, universally

understood communication of facial expressions. His research in basic human

emotions sets forth the idea of their understand-ing across cultures and ages.

It further supports the provocative idea that facial expressions of the

listener may generate auto-nomic and central nervous system changes not only

within the listener but within the one being heard, and vice versa. Indeed, the

evidence is growing that new experiences in clinical interac-tions create

learning and new memories, which are associated with changes in both brain

structure and function (Kandel, 1999; Gabbard, 2000; Mohl, 1987; Liggan and

Kay, 1999). When we listen in this way, we are intervening not only in a

psychological manner to connect, heal, and share burdens but also in a

neuro-biological fashion to regulate, modulate and restore functioning. When

patients feel found, they are responding to this psychobio-logical process.

Related Topics