Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Listening to the Patient

Common Blocks to Effective Listening

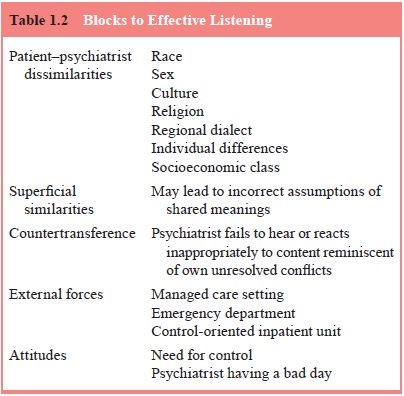

Common Blocks

to Effective Listening

Many factors influence the ability to listen.

Psychiatrists come to the patient as the product of their own life experiences.

Does the listener tune in to what he or she hears in a more attentive way if

the listener and the patient share characteristics? What blocks to listening

(Table 1.2) are posed by differences in sex, age, religion, socioeconomic

class, race, culture, or nationality (Kleinman, 2001; Comas-Diaz and Jacobsen,

1991; Kochman, 1991)? What blind spots may be induced by superficial

similari-ties in different personal meanings attributed to the same cultural symbol?

Separate and apart from the differences in the develop-ment of empathy when the

dyad holds in common certain fea-tures, the act of listening is inevitably

influenced by similarities and differences between the psychiatrist and the

patient.

Would a woman have reported the snoring in Clinical

Vi-gnette 4 or would she have been too embarrassed? Would she have reported it

more readily to a woman psychiatrist? What about the image in Clinical Vignette

2 of a truck sitting on some-one’s chest? How gender and culture bound is it?

Would “The Andy Griffith Show”, important in Clinical Vignette 3, have had the

same impact on a young African-American boy that it did on a Caucasian one? In

how many countries is “The Andy Griffith Show” even available, and in which

cultures would that model of a family structure seem relevant? Suppose the

psychiatrist in that vignette was not a television viewer or had come from

an-other country to the USA long after the show had come and gone? (Roughly 50%

of current residents in psychiatry in the USA are foreign born and trained

[American Psychiatric Association, 2001].) Consider these additional examples.

It is likely that different life experiences based

on gen-der fostered this misunderstanding. How many women easilyidentify with

the stereotyped role of the barnyard rooster? How many men readily identify

with the role of a prostitute? These are but two examples of the myriad

different meanings our specific gender may incline us towards. Although

metaphor is a powerful tool in listening to the patient, cross-cultural

barriers pose poten-tial blocks to understanding.

Even more subtle regional variations may produce

similar problems in listening and understanding.

Psychiatrists discern meaning in that which they

hear through filters of their own – cultural backgrounds, life expe-riences,

feelings, the day’s events, their own physical sense of themselves,

nationality, sex roles, religious meaning systems and intrapsychic conflicts.

The filters can serve as blocks or as magnifiers if certain elements of what is

being said resonate with something within the psychiatrist. When the filters

block, we call it countertransference or insensitivity. When they magnify, we

call it empathy or sensitivity. One may observe a theme for a long time

repeated with a different tone, embellishment, inflection, or context before

the idea of what is meant comes to mind. The “lit-tle fella” example in

Clinical Vignette 3 illustrates a message that had been communicated in many

ways and times in exactly the same language before the psychiatrist “got it”.

On discovering a significant meaning that had been signaled before in many

ways, the psychiatrist often has the experience, “How could I have been so

stupid? It’s been staring me in the face for months!”

Managed care and the manner in which national

health sys-tems are administered can alter our attitudes toward the patient and

our abilities to be transforming listeners. The requirement for authorization

for minimal visits, time on the phone with uti-lization review nurses

attempting to justify continuing therapy, and forms tediously filled out can be

blocks to listening to the patient. Limitations on the kinds and length of

treatment can lull the psychiatrist into not listening in the same way or as

intently. With these time limits and other “third party payer” considera-tions

(i.e., need for a billable diagnostic code from the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV-TR] or the International

Classifi cation of Diseases, 10th

Revision [ICD-10]), the psychiatrist, as careful listener, must heed the

external pressures influencing the approach to the patient. Many health

benefits packages will provide coverage in any therapeutic setting only for

relief of symptoms, restoration of minimal function, acute problem solving, and

shoring up of defenses. In various countries, health care systems have come up

with a variety of constraints in their efforts to deal with the costs of care.

Unless these pressures are attended to, listening will be accomplished with a

different purpose in mind, more closely

approximating the crisis intervention model of the

emergency room or the medical model for either inpatient or outpatient care. In

these settings, the thoughtful psychiatrist will arm himself or herself with

checklists, inventories, and scales for objectifying the severity of illness

and response to treatment: the ear is tuned only to measurable and observable

signs of responses to therapy and biologic intervention.

With emphasis on learning here and now symptoms

that can bombard the dyad with foreground static and noise, will the patient be

lost in the encounter? The same approach to listen-ing occurs in the setting of

the emergency department for crisis intervention. Emphasis is on symptom

relief, assurance of ca-pacities to keep oneself safe, restoration of minimal

function, acute problem solving and shoring up of defenses. Special atten-tion

is paid to identifying particular stressors. What can be done quickly to change

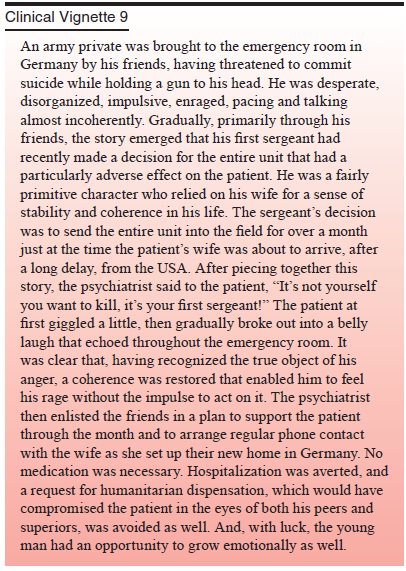

stressors that threw the patient’s world into a state of disequilibrium? The

difference in the emergency room is that the careful listener may have 3 to 6

hours, as opposed to three to six sessions for the patient with a health

maintenance organization or preferred provider contract, or other limitations

on benefits. If one is fortunate and good at being an active

lis-tener–bargainer, the seeds of change can be planted in the hope of allowing

them time to grow between visits to the emergency department. If one could hope

for another change, it would be for a decrease in the chaos in the patient’s

inner world and outer world.

Related Topics