Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Spinal, Epidural & Caudal Blocks

Epidural Anesthesia

Epidural Anesthesia

Continuous epidural anesthesia is a neuraxial

technique offering a range of applicationswider than the typical

all-or-nothing, single dose spinal anesthetic. An epidural block can be

per-formed at the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical level. Sacral epidural

anesthesia is referred to as a caudalblock and is described at the end of this

chap-ter. Epidural techniques are widely used forsurgical anesthesia, obstetric

analgesia, postopera-tive pain control, and chronic pain management. Epidurals

can be used as a single shot technique or with a catheter that allows intermittent

boluses and/ or continuous infusion. The motor block can range from none to

complete. All of these variables are controlled by the choice of drug,

concentration, dos-age, and level of injection.

The epidural space surrounds the dura mater posteriorly, laterally, and

anteriorly. Nerve roots travel in this space as they exit laterally through the

foramen and course outward to become peripheral nerves. Other contents of the

lumbar epidural space include fatty connective tissue, lymphatics, and a rich

venous (Batson’s) plexus. Fluoroscopic studies have suggested the presence of

septa or connective tissue bands within the epidural space, possibly explaining

the occasional one-sided epidural block.

Epidural anesthesia is slower in onset (10–20

min) and may not be as dense as spinal anesthesia. This can be manifested as a

more pronounced differential block or a segmental block, a feature that can be

useful clinically. For example, by using rela-tively dilute concentrations of a

local anesthetic combined with an opioid, an epidural provides anal-gesia

without motor block. This is commonly employed for labor and postoperative

analgesia. Moreover, a segmental block is possible because the anesthetic can

be confined close to the level at which it was injected. A segmental block is

characterized by a well-defined band of anesthesia at certain nerve roots;

leaving nerve roots above and below

unblocked. This can be seen with a thoracic epidural that provides upper

abdominal anesthesia while sparing cervical and lumbar nerve roots.

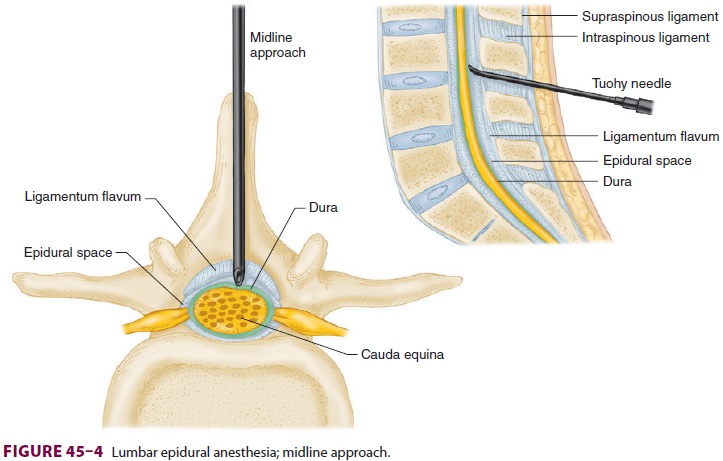

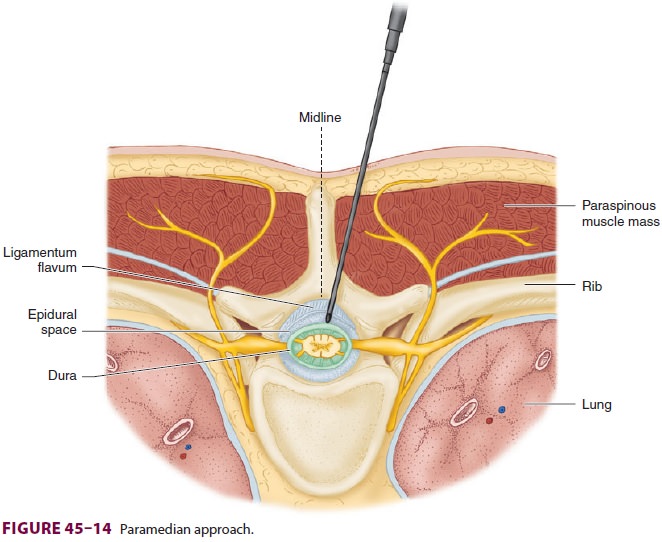

Epidural anesthesia and analgesia is most often performed in the lumbar

region. The mid-line (Figure 45–4) or paramedian approach ( Figure 45–14) can

be used. Lumbar epidural anes-thesia can be used for any procedure below the

diaphragm. Because the spinal cord typically ter-minates at the L1 level, there

is an extra measure of safety in performing the block in the lower lumbar

interspaces, particularly if an accidental dural punc-ture occurs (see

“Complications”).

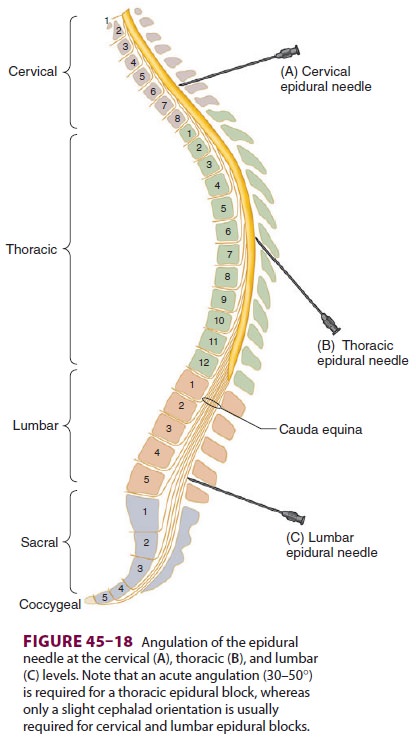

Thoracic epidural blocks are technically more difficult to accomplish

than are lumbar blocks because of greater angulation and the overlapping of the

spi-nous processes at the vertebral level (Figure 45–18).

Moreover, the potential risk of spinal cord injury with accidental dural puncture,

although exceedingly small with good technique, may be greater than that at the lumbar level. Thoracic epidural blocks can be accomplished

with either a midline or paramedian approach. Rarely used for primary

anesthesia, the thoracic epidural technique is most commonly used for

intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. Single shot or catheter techniques

are used for the manage-ment of chronic pain. Infusions via an epidural

cath-eter are useful for providing prolonged durations of analgesia and may obviate

or shorten postoperative ventilation in patients with underlying lung disease

and following chest surgery.

Cervical blocks are usually performed with the patient sitting, with the

neck flexed, using the mid-line approach. Clinically, they are used primarily

for the management of pain.

Related Topics