Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Spinal, Epidural & Caudal Blocks

Caudal Anesthesia

Caudal Anesthesia

Caudal epidural

anesthesia is a

common regional technique in pediatric patients. It may also be used for

anorectal surgery in adults. The caudal space is the sacral portion of the

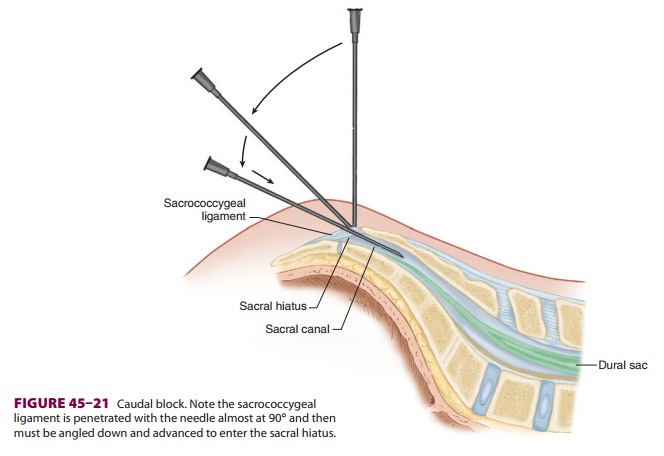

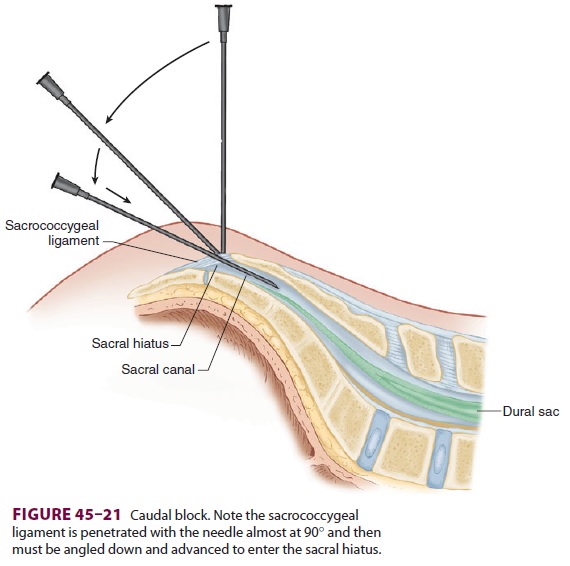

epidural space. Cau-dal anesthesia involves needle and/or catheter penetra-tion

of the sacrococcygeal ligament covering the sacral hiatus that is created by

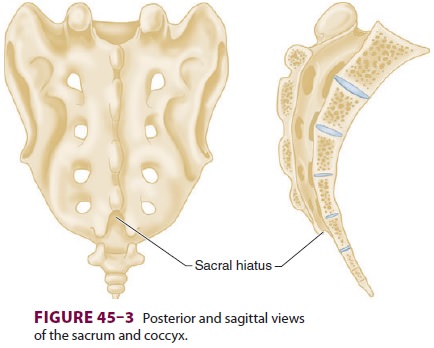

the unfused S4 and S5 lami-nae. The hiatus may be felt as a groove or notch

above the coccyx and between two bony prominences, the sacral cornua (Figure

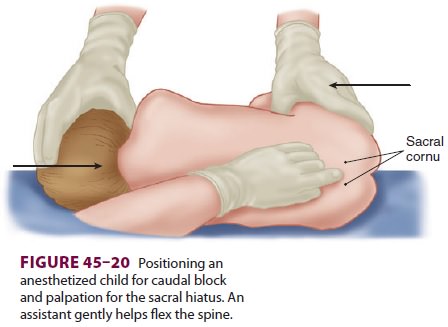

45–3). Its anatomy is more eas-ily appreciated in infants and children (Figure

45–20). The

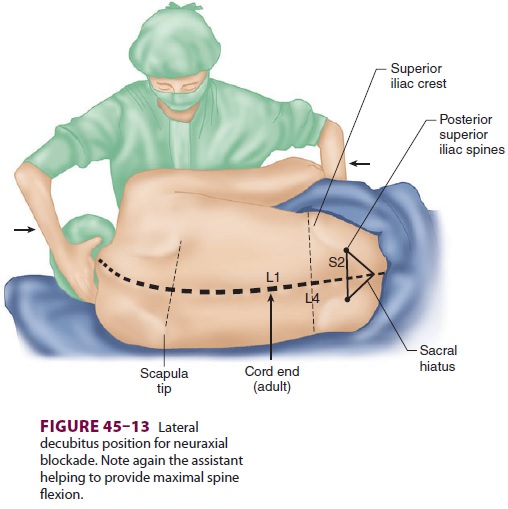

posterior superior iliac spines and the sacral hia-tus define an equilateral

triangle (Figure 45–13). Cal-cification of the sacrococcygeal ligament may make

caudal anesthesia difficult or impossible in older adults. Within the sacral

canal, the dural sac extends to the first sacral vertebra in adults and to

about the third sacral vertebra in infants, making inadvertent intrathecal

injection more common in infants.

In children, caudal anesthesia is typically

com-bined with general anesthesia for intraoperative supplementation and

postoperative analgesia. It is commonly used for procedures below the

dia-phragm, including urogenital, rectal, inguinal, and lower extremity

surgery. Pediatric caudal blocks are most commonly performed after the

induc-tion of general anesthesia. The patient is placed in the lateral or prone

position with one or both hips flexed, and the sacral hiatus is palpated. After

sterile skin preparation, a needle or intravenous catheter

(18–23 gauge) is advanced at a 45° angle cephalad until a

pop is felt as the needle pierces the sacrococ-cygeal ligament. The angle of

the needle is then flat-tened and advanced ( Figure 45–21). Aspiration for blood and CSF is performed, and, if negative,

injec-tion can proceed. Some clinicians recommend test dosing as with other

epidural techniques, although many simply rely on incremental dosing with

fre-quent aspiration. Tachycardia (if epinephrine is used) and/or increasing

size of the T waves on elec-trocardiography may indicate intravascular

injec-tion. Clinical data have shown that the complication rate for pediatric

caudal blocks is low. Complications include total spinal and intravenous

injection, caus-ing seizure or cardiac arrest. Intraosseous injection has also

been reported to cause systemic toxicity.

A dosage of 0.5–1.0 mL/kg of 0.125–0.25%

bupivacaine (or ropivacaine), with or without epi-nephrine, can be used.

Opioids may also be added (eg, 50–70 mcg/kg of morphine), although they are not

recommended for outpatients because of the risk of delayed respiratory

depression. Addition of epinephrine will tend to increase the degree of motor

block. Clonidine is often added or substituted for local anesthetic. The

analgesic effects of the block extend for hours into the postoperative period.

Pedi-atric outpatients can safely be discharged home, even with mild residual

motor block and without urinating, as most children will urinate within 8 hr.

Repeated injections can be accomplished via

repeating the needle injection or via a catheter left in place and covered with

an occlusive dressing after being connected to extension tubing. Higher

der-matomal levels of epidural anesthesia/analgesia can be accomplished with

epidural catheters threaded cephalad into the lumbar or even thoracic epidural

space from the caudal approach in infants and chil-dren. Fluoroscopy can assist

in catheter positioning. Smaller catheters are technically difficult to pass

due to kinking. Catheters advanced into the thoracic

epidural space have been used to achieve

T2–T4 blocks for ex-premature infants undergoing inguinal hernia repair. This

is achieved using chloroprocaine (1 mL/kg) as an initial bolus and incremental

doses of 0.3 mL/kg until the desired level is achieved.

In adults undergoing anorectal procedures,

caudal anesthesia can provide dense sacral sensory blockade with limited

cephalad spread. Further-more, the injection can be given with the patient in

the prone jackknife position, which is used for surgery (Figure

45–22). A dose of 15–20 mL of 1.5–2.0% lidocaine,

with or without epinephrine, is usually effective. Fentanyl 50–100 mcg may also

be added. This technique should be avoided in patients with pilonidal cysts

because the needle may pass through the cyst track and can potentially

introduce bacteria into the caudal epidural space. Although no longer commonly

used for obstetric analgesia, a cau-dal block can be useful for the second

stage of labor, in situations in which the epidural is not reaching the sacral

nerves, or when repeated attempts at epi-dural blockade have been unsuccessful.

Related Topics