Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Regional Anesthesia & Pain Management: Spinal, Epidural & Caudal Blocks

Anatomy of The Spinal Cord

THE SPINAL CORD

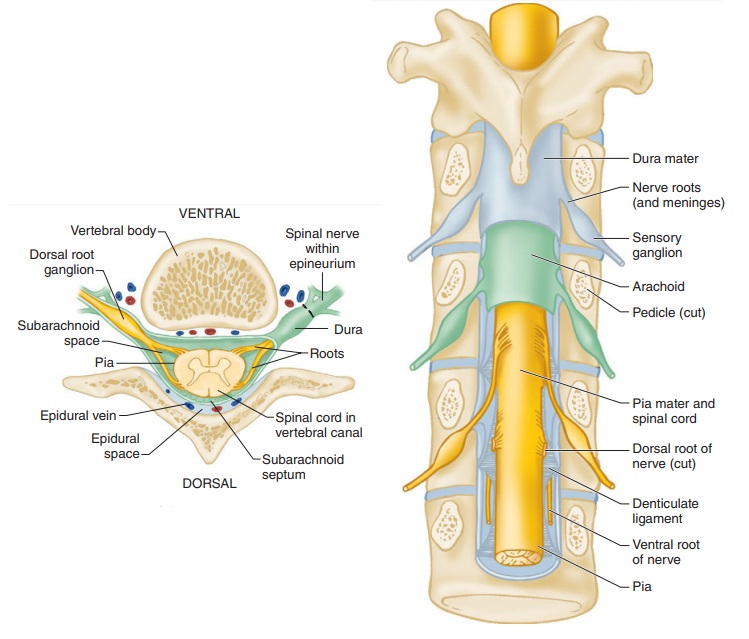

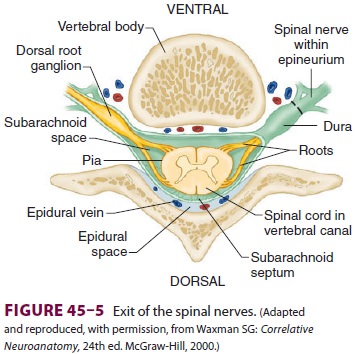

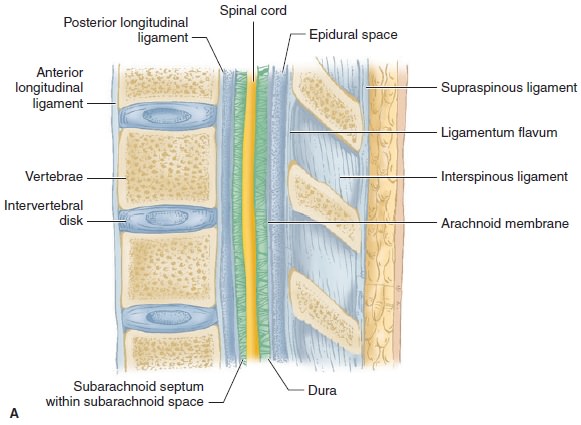

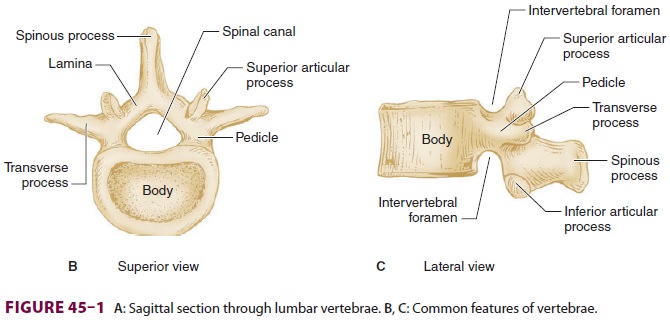

The spinal canal contains the spinal cord

with its coverings (the meninges), fatty tissue, and a venous plexus (Figure

45–5). The meninges are composed of three layers:

the pia mater, the arachnoid mater,

and the dura mater; all are contiguous with their cranial counterparts (

Figure 45–6). The pia mater is closely adherent

to the spinal cord, whereas the arachnoid mater is usually closely adherent to

the thicker and denser dura mater. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is contained between

the pia and arach-noid maters in the subarachnoid space. The spinal subdural

space is generally a poorly demarcated, potential space that exists between the

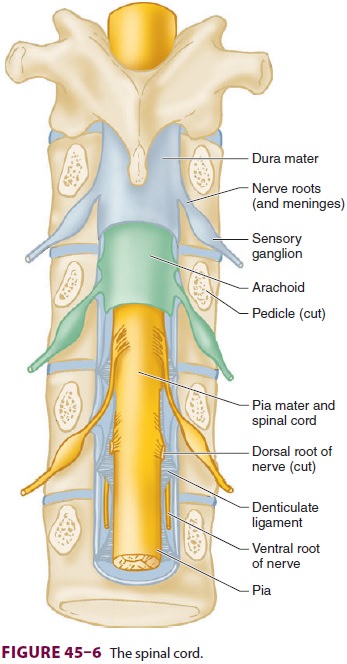

dura and arachnoid membranes. The epidural space is a better defined potential

space within the spinal canal that is bounded by the dura and the ligamentum

flavum (Figures 45–1 and 45–5).

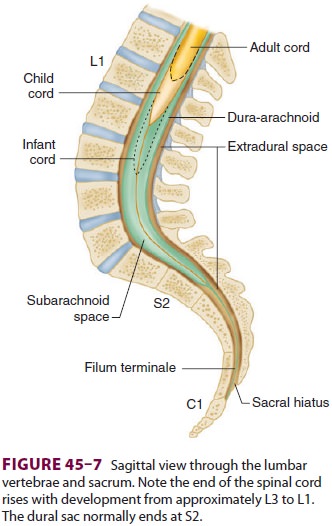

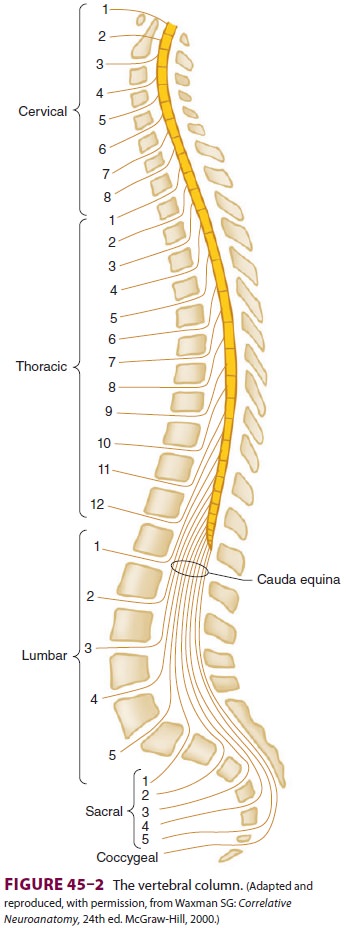

The spinal cord normally extends from the

fora-men magnum to the level of L1 in adults (Figure 45–7). In children, the spinal cord ends at L3 and moves up with age. The

anterior and poste-rior nerve roots at each spinal level join one another and

exit the intervertebral foramina, forming spinal nerves from C1 to S5 (Figure

45–2). At the cervical level, the nerves arise above their respective

verte-brae, but starting at T1, exit below their vertebrae. As a result, there

are eight cervical nerve roots, but only seven cervical vertebrae. The cervical

and upper thoracic nerve roots emerge from the spinal cord and exit the

vertebral foramina nearly at the same level (Figure 45–2). But, because the

spinal cord normally ends at L1, lower nerve roots course somedistance before

exiting the intervertebral foramina. These lower spinal

nerves form the cauda equine (“horse’s tail”; Figure 45–2). Therefore, per-forming

a lumbar (subarachnoid) puncturebelow L1 in an adult (L3 in a child) usually

avoids potential needle trauma to the cord; damage to the cauda equina is unlikely, as these nerve roots float inthe dural

sac below L1 and tend to be pushed away (rather than pierced) by an advancing

needle.

A dural sheath invests most nerve roots for a small distance, even after they exit the spinal canal (Figure 45–5). Nerve blocks close to the intervertebral foramen therefore carry a risk of subdural or subarachnoid injection. The dural sac and the subarachnoid and subdural spaces usually extend to S2 in adults and often to S3 in children. Because of this fact and the smaller body size, cau-dal anesthesia carries a greater risk of subarachnoid injection in children than in adults. An extension of the pia mater, the filum terminale, penetrates the dura and attaches the terminal end of the spinal cord (conus medullaris) to the periosteum of the coccyx (Figure 45–7).

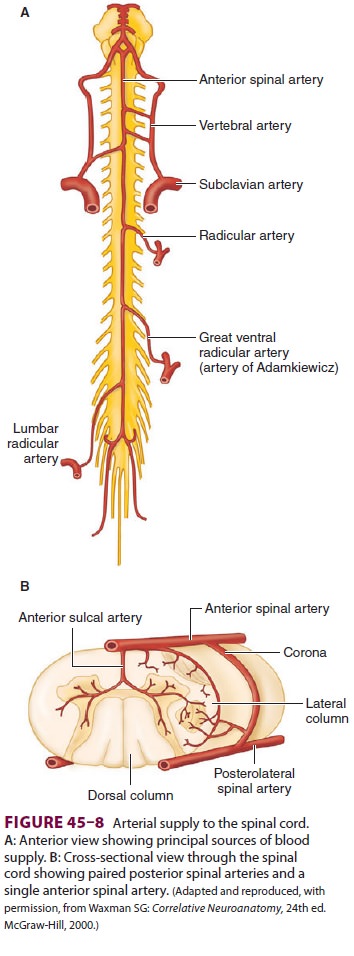

The blood supply to the spinal cord and nerve

roots is derived from a single anterior spinal artery and paired posterior

spinal arteries ( Figure 45–8).

The anterior spinal artery is formed from the verte-bral artery at the base of

the skull and courses down along the anterior surface of the cord. The anterior

spinal artery supplies the anterior two-thirds of the cord, whereas the two

posterior spinal arteries supply the posterior one-third. The posterior spinal

arteries arise from the posterior inferior

cerebellar arteries and course down along the dorsal surface of the cord medial

to the dorsal nerve roots. The ante-rior and posterior spinal arteries receive

additional blood flow from the intercostal arteries in the tho-rax and the

lumbar arteries in the abdomen. One of these radicular arteries is typically

large, the artery of Adamkiewicz, or arteria radicularis magna, arising from

the aorta (Figures 45–8A). It is typically uni-lateral and nearly always arises

on the left side, pro-viding the major blood supply to the anterior, lower

two-thirds of the spinal cord. Injury to this artery can result in the anterior

spinal artery syndrome.

Related Topics