Chapter: Biotechnology Applying the Genetic Revolution: Molecular Biology of Cancer

Detection of Oncogenes by Transformation

DETECTION OF ONCOGENES

BY TRANSFORMATION

If DNA is extracted from cancer

cells and is then inserted into healthy cells, it may change them into cancer

cells. This is known as transformation.

(Note that transformation has a

related but different meaning in bacterial genetics, where it refers to the

uptake and incorporation of any foreign DNA.) Thus, if the presence of an

oncogene is suspected, this can be tested by adding a sample of the suspect DNA

to suitable cells in culture.

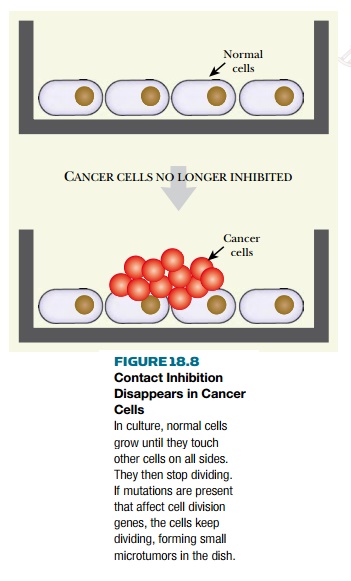

Normal cultured animal cells usually

grow as a thin monolayer on the surface of a culture dish. They do not normally

crawl on top of each other or pile up into heaps (Fig. 18.8). Once the cells on

all sides, they stop dividing, a phenomenon known as contact inhibition. In contrast, cancer cells are uninhibited and

they continue to divide and to aggregate into heaps (see Fig. 18.8). Such

miniature heaps of cells can be seen when DNA containing an oncogene is added

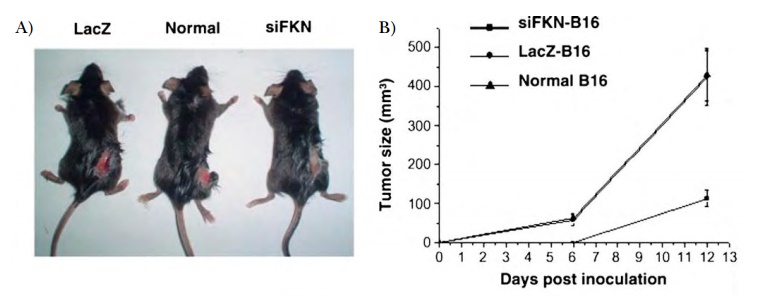

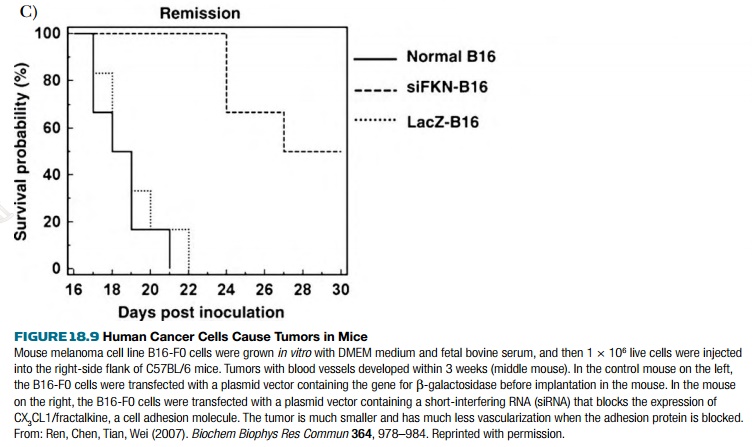

to normal cells in culture. These heaps may be regarded as tiny tumors. If

cells from these heaps are injected into an experimental animal such as a

mouse, a real tumor will form (Fig. 18.9).

A related feature of cancer cells is

anchorage independence. Unlike most

normal cells, cancer cells can grow and divide in the absence of binding to

proteins of the extracellular matrix. As a consequence, such cancer cells can

move around and proliferate in “incorrect” locations in the body. This behavior

is especially prominent in malignant (as opposed to benign) tumors.

Related Topics