Chapter: Biotechnology Applying the Genetic Revolution: Immune Technology

Antibody Structure and Function

ANTIBODY

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The world is full of

infectious microorganisms, all looking for a suitable host to infect. Bacteria,

viruses, and protozoans are constantly attempting to gain entry into our

tissues. If nothing was done about these attempts at invasion, no human could

survive. Fortunately, cells of the immune system patrol the internal tissues,

the bloodstream, and the body surfaces, both outside and inside, protecting the

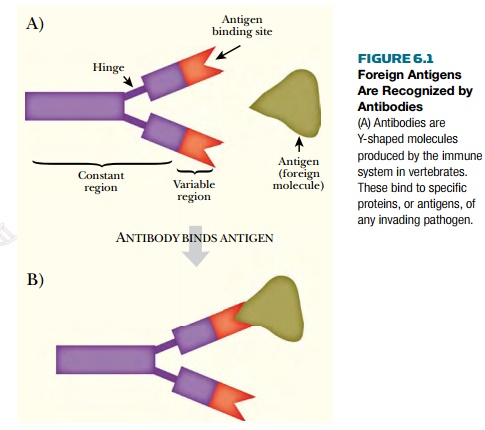

entire organism from attack. Any foreign macromolecules that are not recognized

as being “self” will be regarded as signs of an intrusion and will trigger an

immune response. Invading microorganisms have their own distinctive proteins,

which differ in sequence and therefore in 3-D structure from those of the host

animal. In particular, those molecules exposed on the surfaces of invading

microorganisms will attract the attention of the immune system. These foreign

molecules are referred to as antigens,

and the immune system molecules that recognize and bind to them are known as antibodies (Fig. 6.1).

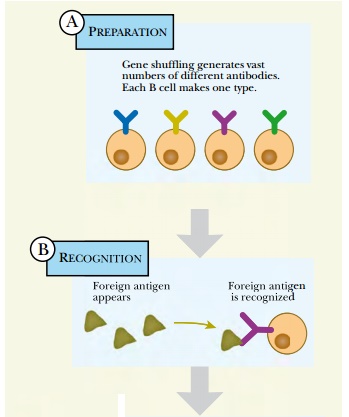

Although we often speak as if

the body makes antibodies in response to invasion by a foreign antigen, this is

rather misleading. In fact, long before infection, the immune system generates

billions of different antibodies. Each B

cell of the immune system has the capability to make just one of these. The

immune system keeps a few B cells on standby for each of its colossal

repertoire of antibodies. This happens before encountering the antigens and

without knowing which antibodies will actually be needed later. If enough

different antibodies are available, at least one or two should match an antigen

of any conceivable shape, even if the body has never come into contact with it

before.

Eventually, a foreign antigen

appears (Fig. 6.2). Among the billions of predesigned antibodies, at least one

or two will fit the antigen reasonably well. Those B cells that make antibodies

that recognize the antigen now divide rapidly and go into mass production. Thus

the antigen determines which antibody is amplified and produced. Once a

matching antibody has bound invading antigens, the immune system brings other

mechanisms into play to destroy the invaders.

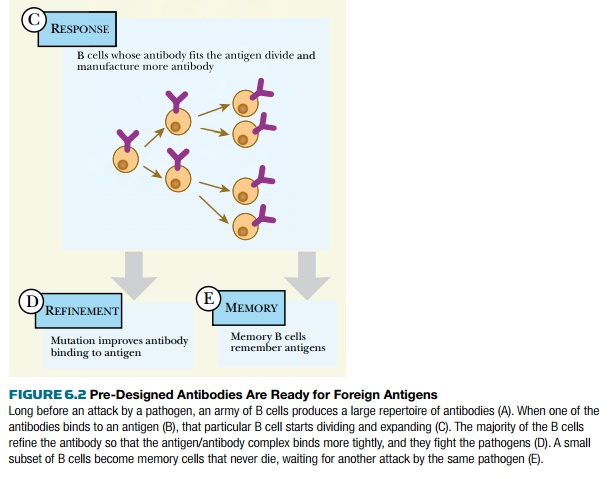

Sometime later there is a

stage of refinement during which those antibodies that bound to the invading

antigen are modified by mutation to fit the antigen better. In addition, the

immune system keeps a record of antibodies that are actually used. If the same

invader ever returns, the corresponding antibodies can be rushed into action,

faster and in greater numbers than before. Vaccines exploit this capacity by

stimulating the immune system to store the antibodies that recognize and

destroy a pathogenic virus such as smallpox. Yet the vaccines cause no disease

symptoms themselves (see later discussion).

Related Topics