Chapter: 11th Zoology : Chapter 4 : Organ and Organ Systems in Animals

Anatomy of Pigeon: Endoskeleton, Digestive, Respiratory, Circulatory, Arterial, Nervous, Venous system

Anatomy

Endoskeleton

The skeletal system is strong but lightly built. The bones are light and spongy. Many of the long bones contain air instead of marrow (Pneumatic bones). This reduces the weight of the body. The breast bone or sternum has a broad plate of bone produced ventrally into a prominent vertical crest or keel to which the powerful muscles of flight are attached.

Flight muscles

Wings are modified forelimbs and the organs of flight. The musculature of the forelimbs are greatly modified in response to the function they perform. Flight is the coordinated effort of a number of paired muscles. The muscles which operate the wings during flight are called flight muscles. The major flight muscles of pigeon are the pectoral muscles. Pectoral muscles are of two types namely the Pectoralis major and Pectoralis minor. The pectoralis major muscle is a large and powerful flight muscle which arises from the sternum.

Contraction of these muscles lower the wings in flight. Pectoralis minor (subclavius) is small and elongated muscle which elevates the wings during flight. Besides the pectoralis, the small coracobrachialis muscle also helps to pull the wings down and to rotate wings during flight.

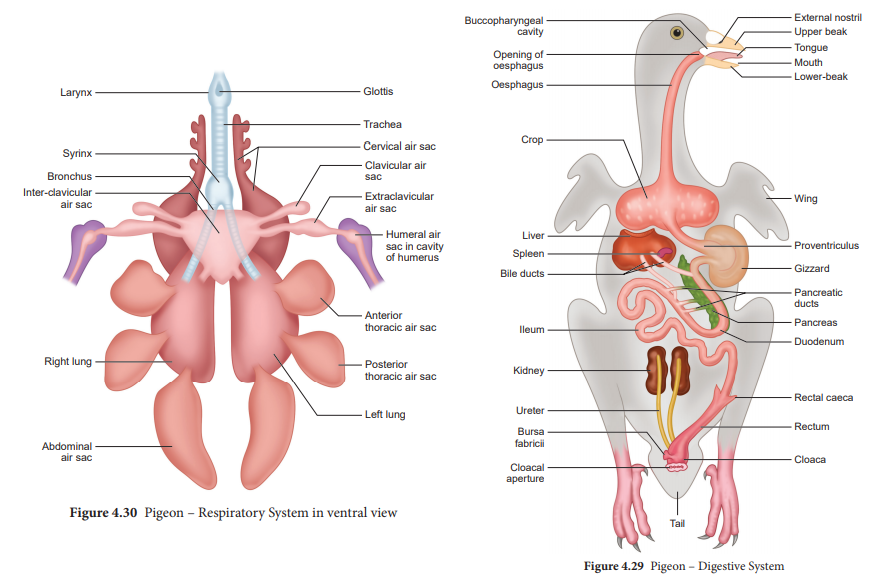

Digestive System

The long coiled alimentary canal consist of buccal cavity, pharynx, oesophagus, crop, stomach, small intestine and Large intestine. (Figure 4.29).

Mouth is covered by a toothless, horny, upper and lower beaks. Behind the mouth, there is a wide buccal cavity.

In the floor of the buccal cavity, a large, narrow, horny tongue is present with scanty sensory papillae and numerous mucus glands. Buccal cavity leads into the pharynx fol-lowed by the oesophagus, which enlarges to form a thin walled, bilobed elastic sac, the crop. The crop serves as a food res-ervoir. Beyond the crop the oesophagus enters the stomach which is differentiat-ed into anterior glandular proventriculus and a posterior muscular ventriculus or gizzard. The proventriculus has a mucus lining which secretes the gastric juice. The walls of the gizzard is thick, muscular and has many tubular glands. The cavity of the gizzard contains grit or small peb-bles called gastroliths that are swallowed by the bird. These stones helps the bird in grinding the food. The gizzard leads to a small intestine which consists of a ‘U’ shaped duodenum and ileum. The pan-creas lies between the two limbs of the duodenum and receives three ducts from the pancreas and two bile ducts from the liver. The inner lining of the ileum con-tains numerous villi which helps in ab-sorption. The ileum continues into the large intestine, which is short and is dif-ferentiated into rectum and cloaca. A pair of small blind pouches called rectal caeca is present at the junction of the ileum and rectum. The rectum leads into the cloaca which is divided into the anterior copro-daeum into which the rectum opens, the middle urodaeum into which the urini-genital ducts open, and the posterior ves-tibule or proctodaeum, which opens to the outside by the cloacal aperture.

Buccal glands, salivary glands, gas-tric glands, liver, pancreas and intestinal glands are the digestive glands which en-hance the process of digestion in pigeon. There is no gall bladder in the pigeon though present in many other birds. Pi-geons produce ‘milk’, a cheesy and nour-ishing secretion, from both the sexes. It is formed by the degeneration of the epithe-lial cells lining the crop. It is regurgitated and fed to the young birds.

The pigeon feeds on grains. As birds have no teeth, the food swallowed by it passes through the gullet or oesophagus into the crop where it is stored. There are mucous glands in the crop; food is softened by being mixed with the mucus and the se-cretion of the buccal glands, aided by the warmth of the body. The food then enters the stomach, where it is digested by gastric juices secreted in the proventriculus; the food is also crushed in the gizzard with aid of gastroliths. The food is thus reduced to smaller particles and the partly digested food passes into the intestine where it is mixed with the bile and pancreatic juice, and further digestion is effected.

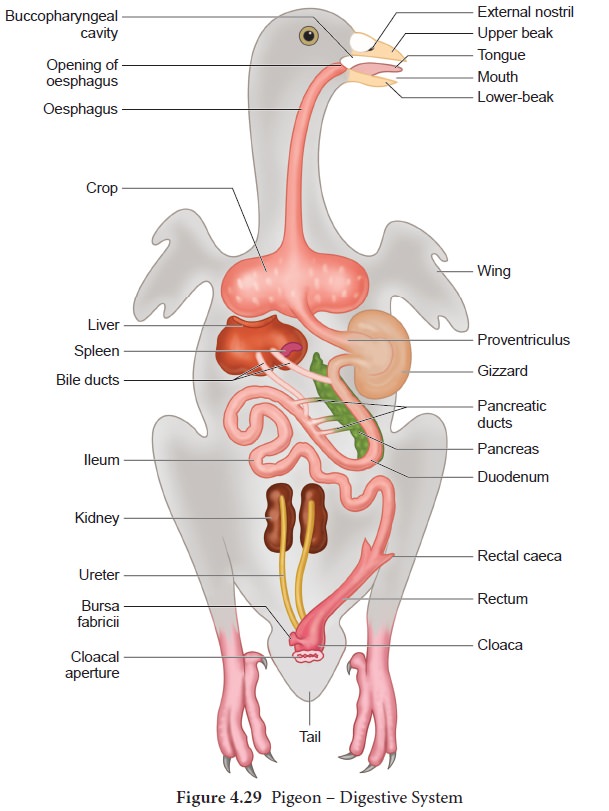

Respiratory system

In birds the type of respiration is pulmonary. The respiratory system includes the respiratory tract, the respiratory organs and air sacs. A true muscular diaphragm is absent in birds. The respiratory tract includes the nares, nasal sacs, glottis, larynx, trachea and syrinx. The respiratory organs are the lungs and air sacs. The larynx opens into the trachea and is supported by a series of closely set rings. The trachea divides into two bronchi, each of which divides and sub-divides into smaller branches, ultimately ending in fine air-capillaries which lies intermingled with the capillaries of the pulmonary vessels. Lungs are solid spongy organs; attached dorsally to the ribs. There are nine air-sacs: a pair of cervical sacs at the base of the neck one on each side; a single median interclavicular air sac connected with both lungs and situated in between the two limbs of the furcula and on either sides it gives off an extraclavicular air sac communicating with an air - cavity of the humerus and a clavicular air sac; two pairs of thoracic air sacs and a pair of abdominal air sacs. This complicated arrangement adds to the efficient respiratory function and maintenance of a high temperature (Figure 4.30).

Respiratory mechanism

The lungs are not dilatable since the skeleton around them forms a rigid framework. Inspiration is passive and expiration is an active process. During respiration the sternum is drawn towards the vertebral column, by contraction of the muscles of the body-wall. As is drawn up, the elastic ribs are bent so as to bring about a decrease in the size of the body cavity and the air from the lungs is forced out. When the muscles relax, the body-cavity recovers its size and air is drawn in.

Syrinx

The larynx does not take part in the production of voice. The voice box lies deep down where the trachea divides into two bronchi, and is known as syrinx, a structure characteristic of birds. It consists of a chamber with its walls supported by three or four rings of the trachea and the first ring of each bronchus; its inner lining is raised into folds, the vibrations of which is caused by the movement of air results in the production of sound.

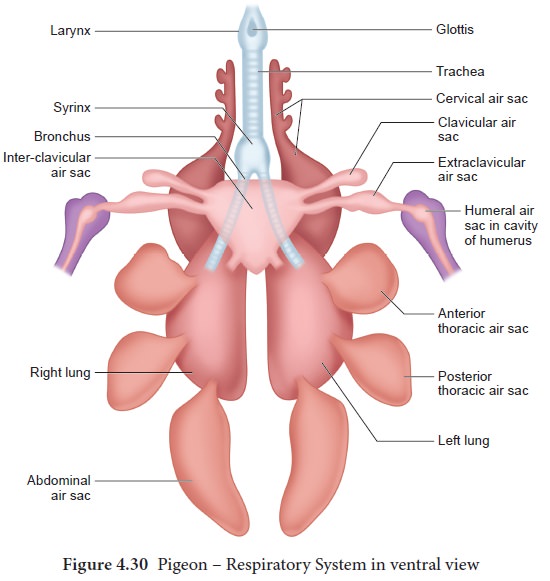

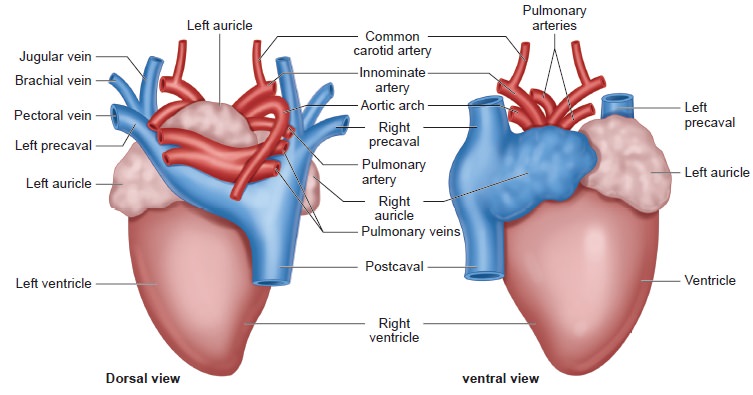

Circulatory system

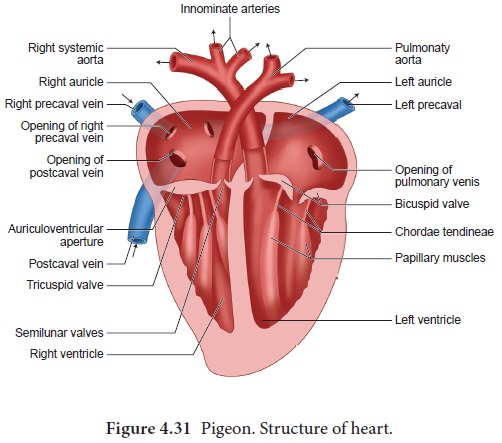

Pigeon has an efficient circulatory system to meet the metabolic demands of flight, but also plays a significant role in maintaining the body temperature. The circulatory system of pigeon includes the heart and blood vessels. The heart of the pigeon is four chambered with two auricles and two ventricles. There is no sinus venosus. The two precaval veins or superior venae cavae, a post caval vein or inferior vena cava opens into the right auricle; the pulmonary aorta and systemic trunks arise from the right and left ventricles respectively. The right side of the heart is completely separated from the left side of the heart by a septum. The right auricle opens into the right ventricle by the right auriculo -ventricular aperture and the left auricle into the left ventricle by the left auriculo- ventricular aperture. There are valves at these apertures, which allows the blood to flow only in one direction, i.e., from the auricle into the ventricle but not backwards. The right auriculo-ventricular valve consists of a single flap without connecting chordae tendinae; the valve on the left side has two flaps connected to the papillary muscles by chordae tendinae. The pulmonary aorta arises from the right ventricle and the aortic arch from the left ventricle. The pulmonary veins open into the left auricle. There are three semilunar valves at the junction of the pulmonary aorta and the right ventricle. The pulmonary aorta divides into two branches, each entering a lung. Only the right aortic arch is present in birds.

The right auricles of the heart receives venous blood from all parts of the body except the lungs, through the precaval and post caval veins. The right ventri-cles pumps venous blood into the lungs through the pulmonary aorta. The oxy-genated blood from the lungs is returned to the left auricle through the pulmonary veins. From the left ventricle a single right aortic arch carries oxygenated blood to the different parts of the body. The right half of the heart receives and discharges only venous blood and the left half only arterial blood. Thus birds possess a com-plete double circulation which includes the pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. (Figure 4.31).

The arterial system

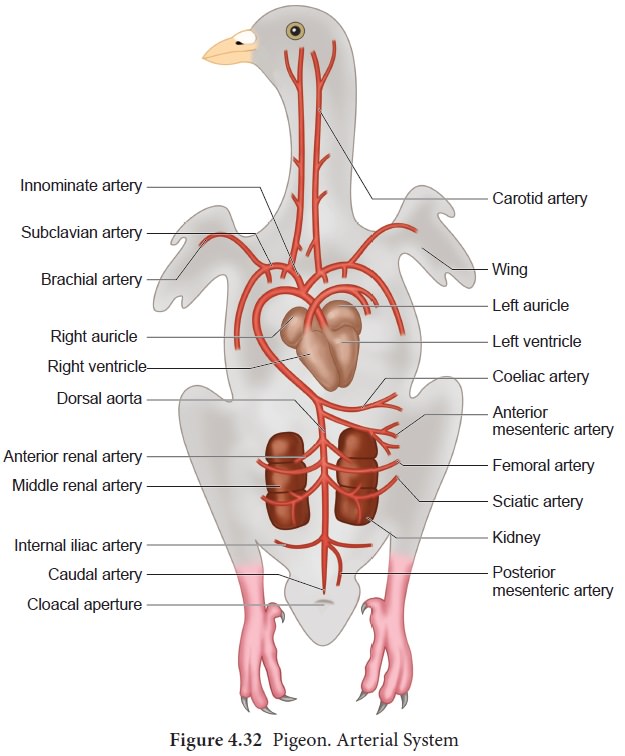

The right aortic arch curves over to the right side giving off at the curve the right and the left innominate arteries; each of these gives rise to a carotid artery and a subclavian artery, the former carrying blood to the brain.

The subclavian artery divides into a brachial artery conveying blood to the arm, and a pectoral artery to the muscles of the wings. The aortic arch passes backwards as the dorsal aorta, from which are given off the unpaired coeliac artery supplying blood to the stomach, the liver and few parts of intestine; the unpaired anterior mesenteric artery to the great part of the intestine; the paired anterior renal arteries to the anterior lobes of the kidney; the paired femoral arteries supplying blood to the anterior region of the thigh and the paired sciatic arteries supply blood to the posterior parts of the thighs and the leg.

From the each sciatic artery arises a middle renal artery to the middle lobe of the kidney and a posterior renal artery to the posterior lobe; the unpaired posterior mesenteric artery supplies blood to the rectum and the cloaca; the paired internal iliac arteries to the pelvis and the caudal artery which is the terminal portion of the dorsal aorta extends to the tail (Figure 4.31).

The venous system

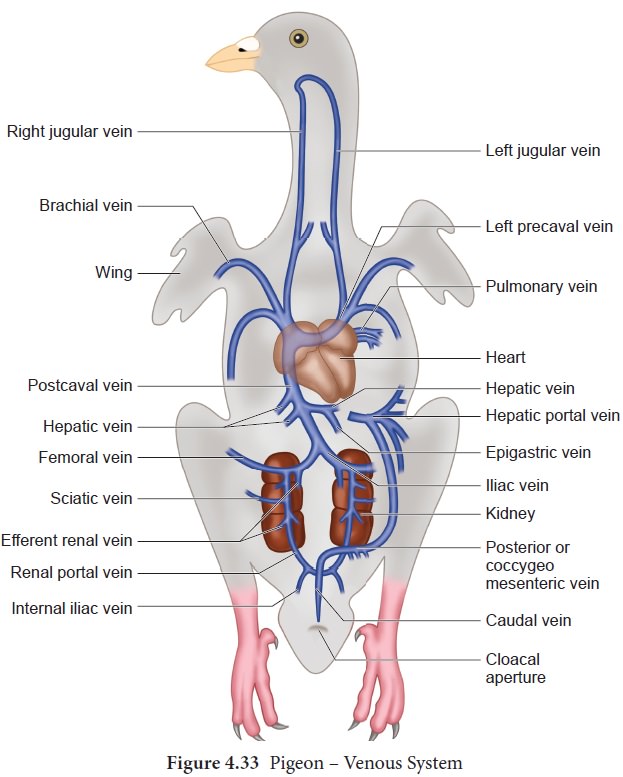

The precaval vein of each side is formed by the union of the jugular vein from the head, the brachial vein from the arm, and the pectoral vein from the pectoral muscles. The jugular vein of the two sides are connected in front by a transverse vessel. The postcaval vein is formed by the union of the two iliac veins in front of the kidney. Each iliac vein is in turn formed by the union of the femoral vein from the leg, an efferent renal vein from the kidney, and the renal-portal vein from the posterior regions. The hepatic-portal circulation is present and the blood from the liver is emptied into the postcaval vein by three hepatic veins. (Figure 4.33).

The caudal vein from the tail divides into the right and the left renal-portal vein each of which enters the kidney. Be-fore entry, the renal-portal vein is joined by the internal iliac vein from the pelvis. As the renal-portal vein passes through the kidney, it receives the sciatic and the femoral vein from the leg, and final ly emerges from the kidneys as the iliac vein. The renal- portal veins do not break into capillaries in the kidney but only send a few small branches; renal -portal circulation is therefore not well devel-oped in the bird.

At the place of bifurcation of the cau-dal vein into the two renal-portal veins arises the median coccygeomesenter-ic vein which is characteristic of birds.

This vein runs forward, receives in its course veins from the rectum, and joins the hepatic portal vein. The epigastric vein returns the blood from the mesen-teries and joins one of the hepatic veins.

Nervous system and receptor organs

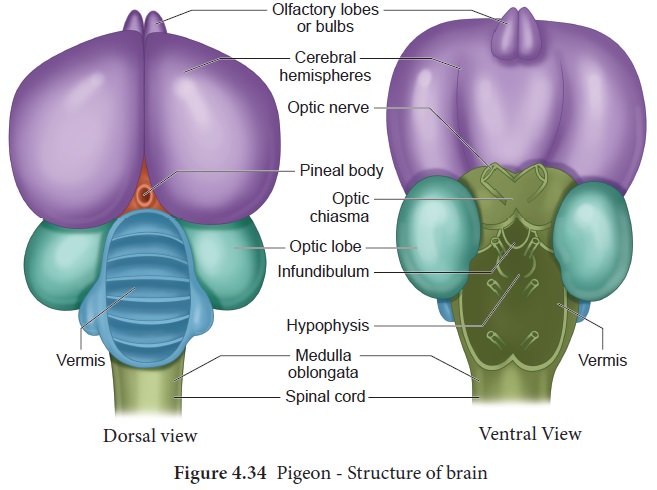

The nervous system consists of central nervous system which includes the brain and spinal cord, the peripheral nervous system and the autonomous nervous system (Figure 4.34). The brain of pigeon is larger than in lower forms, it is short, broad and rounded within cranial cavity. It is covered by two meninges, the outer duramater and an inner pia- arachnoid membrane and the space between the two meninges is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. The cerebral hemispheres of the pigeon are large and extend behind to meet the cerebellum. The cerebrum controls voluntary movements and is the centre for memory and intelligence. The diencephalon is covered dorsally by the cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum. The diencephalon relays impulses to the cerebral hemispheres, integrates the autonomic system and the perception of extreme cold, pain, heat etc. On the ventral side of the diencephalon is the optic chiasma, behind the chiasma projects the infundibulum bearing a large hypophysis or pituitary. The optic lobes are large and occupy a lateral position owing to the large size of the cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum. Optic lobes are centres for sight. The pineal body and infundibulum are present. The cerebellum is highly developed and convoluted indicating the delicate sense of equilibrium and the great power of muscular co-ordination required for birds.

The cerebellum extends backwards covering a large part of the medulla oblongata which descends downwards to join the spinal cord. The medulla oblongata controls the involuntary movement. The olfactory lobes or bulbs are small and degenerate due to poorly developed organs of smell.

The peripheral nervous system consists of 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 38 pairs of spinal nerves. The autonomic nervous system of pigeon includes the sympathet-ic and parasympathetic nervous system. It contains the nerves and ganglia. The sympa-thetic nerves supply the alimentary, respira-tory, circulatory and urinogenital systems.

Sense organs

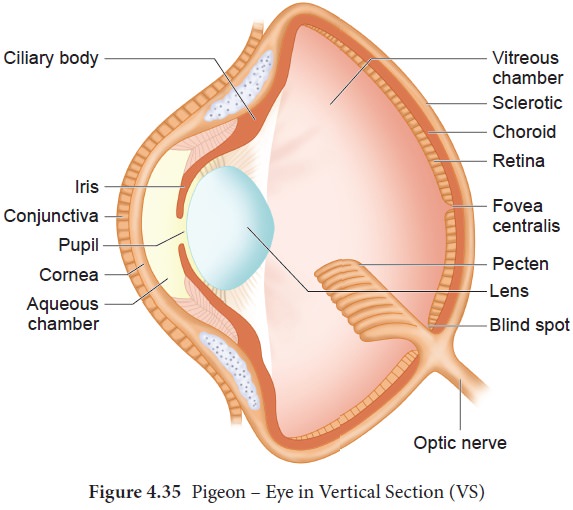

Eyes are large and well developed; they are not spherical, but biconvex. The sclerotic coat contains bony plates. There is a vascular pigmented plaited process known as the pecten, projecting into the vitreous body from the point where the optic nerve enters the eye (Figure 4.35). Pecten is concerned with the power of accommodation which is greatly developed in birds. The muscles for the movement of the eye-balls are reduced. In the ear, the cochlea is well developed. The two eustachian tubes unite and open by a common aperture on the roof of the buccal cavity. The olfactory sense is poorly developed.

Related Topics