Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Musculoskeletal Disorders

Acute Low Back Pain

Common

Musculoskeletal Problems

ACUTE LOW BACK PAIN

The number of medical visits resulting from low back pain

is sec-ond only to the number of visits for upper respiratory illnesses. Most

low back pain is caused by one of many musculoskeletal problems, including

acute lumbosacral strain, unstable lum-bosacral ligaments and weak muscles,

osteoarthritis of the spine, spinal stenosis, intervertebral disk problems, and

unequal leg length.

Older patients may experience back pain associated with

os-teoporotic vertebral fractures or bone metastasis. Other causes in-clude

kidney disorders, pelvic problems, retroperitoneal tumors, abdominal aneurysms,

and psychosomatic problems.

In addition, obesity, stress, and occasionally depression

may contribute to low back pain. Back pain due to musculoskeletal disorders

usually is aggravated by activity, whereas pain due to other conditions is not.

Patients with chronic low back pain may develop a dependence on alcohol or

analgesics in an attempt to cope with and self-treat the pain.

Pathophysiology

The spinal column can be considered as an elastic rod

constructed of rigid units (vertebrae) and flexible units (intervertebral

disks) held together by complex facet joints, multiple ligaments, and

paravertebral muscles. Its unique construction allows for flexibil-ity while

providing maximum protection for the spinal cord. The spinal curves absorb

vertical shocks from running and jumping. The trunk muscles help to stabilize

the spine. The abdominal and thoracic muscles are important in lifting

activities. Disuse weakens these supporting structures. Obesity, postural

problems, struc-tural problems, and overstretching of the spinal supports may

re-sult in back pain.

The intervertebral disks

change in character as a person ages. A young person’s disks are mainly

fibrocartilage with a gelatinous matrix. As a person ages, the disks become

dense, irregular fibro-cartilage. Disk degeneration is a common cause of back

pain. The lower lumbar disks, L4–L5 and L5–S1, are subject to the great-est

mechanical stress and the greatest degenerative changes. Disk protrusion

(herniated nucleus pulposus) or facet joint changes can cause pressure on nerve

roots as they leave the spinal canal, which results in pain that radiates along

the nerve.

Clinical Manifestations

The patient complains of

either acute back pain or chronic back pain (lasting more than 3 months without

improvement) and fa-tigue. The patient may report pain radiating down the leg,

which is known as radiculopathy or sciatica and which suggests nerve root

involvement. The patient’s gait, spinal mobility, reflexes, leg length, leg

motor strength, and sensory perception may be altered. Physical examination may

disclose paravertebral muscle spasm (greatly increased muscle tone of the back

postural muscles) with a loss of the normal lumbar curve and possible spinal

deformity.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The Agency for Heath Care Policy and Research developed

guide-lines for assessment and management of acute low back pain (Bigos et al.,

1994). These safe, conservative, and cost-effective guidelines have reduced the

use of noneffective therapeutic inter-ventions, including prolonged bed rest.

The initial evaluation

of acute low back pain includes a focused history and physical examination,

including general observation of the patient, back examination, and neurologic

testing (reflexes, sen-sory impairment, straight-leg raising, muscle strength,

and muscle atrophy). The findings suggest either nonspecific back symptoms or

potentially serious problems, such as sciatica, spine fracture, can-cer,

infection, or rapidly progressing neurologic deficit. If the ini-tial

examination does not suggest a serious condition, no additional testing is

performed during the first 4 weeks of symptoms.

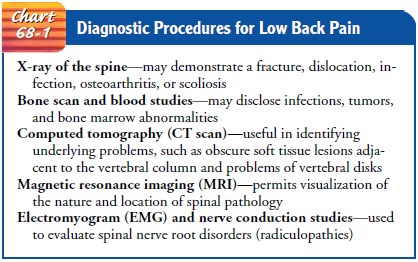

The diagnostic procedures described in Chart 68-1 may be

in-dicated for the patient with potentially serious or prolonged low back pain.

The nurse prepares the patient for these studies, pro-vides the necessary

support during the testing period, and moni-tors the patient for any adverse

responses to the procedures.

Medical Management

Most back pain is self-limited and resolves within 4

weeks with analgesics, rest, stress reduction, and relaxation. Based on initial

assessment findings, the patient is reassured that the assessment indicates

that the back pain is not due to a serious condition. Management focuses on

relief of pain and discomfort, activity modification, and patient education.

Nonprescription analgesics (acetaminophen, ibuprofen) are

usually effective in achieving pain relief. At times, a patient may require the

addition of muscle relaxants or opioids. Heat or cold therapy frequently

provides temporary relief of symptoms. In the absence of symptoms of disease

(radiculopathy of the roots of spinal nerves), manipulation may be helpful.

Other physical modalities have no proven efficacy in treating acute low back pain. They include traction, massage, diathermy, ultrasound, cutaneous laser treatment, biofeedback, and tran-scutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Likewise, acupuncture and injection procedures have no proven efficacy (Bigos et al., 1994).

Most patients need to alter their activity patterns to

avoid ag-gravating the pain. Twisting, bending, lifting, and reaching, all of

which stress the back, are avoided. The patient is taught to change position

frequently. Sitting should be limited to 20 to 50 minutes based on level of

comfort. Bed rest is recommended for 1 to 2 days, with a maximum of 4 days only

if pain is severe. A grad-ual return to activities and low-stress aerobic

exercise is recom-mended. Conditioning exercises for the trunk muscles are

begun after about 2 weeks.

If there is no improvement within 1 month, additional

assess-ments for physiologic abnormalities are performed. Management is based

on findings.

Related Topics