Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract Disorders

Lung Cancer (Bronchogenic Carcinoma)

Chest Tumors

Tumors

of the lung may be benign or malignant. A malignant chest tumor can be primary,

arising within the lung, chest wall, or mediastinum, or it can be a metastasis

from a primary tumor site elsewhere in the body. Metastatic lung tumors occur

frequently because the bloodstream transports cancer cells from pri-mary

cancers elsewhere in the body to the lungs.

LUNG CANCER (BRONCHOGENIC CARCINOMA)

Lung

cancer is the number-one cancer killer among men and women in the United

States, accounting for 31% of cancer deaths in men and 25% in women (American

Cancer Society, 2002; Greenlee et al., 2001). For men, the incidence of lung

cancer has remained relatively constant, but in women it continues to rise.

Lung cancer affects primarily those in the sixth or seventh decade of life;

less than 5% of patients are under the age of 40. In ap-proximately 70% of lung

cancer patients, the disease has spread to regional lymphatics and other sites

by the time of diagnosis. As a result, the long-term survival rate for lung

cancer patients is low. Evidence indicates that carcinoma tends to arise at

sites of previ-ous scarring (TB, fibrosis) in the lung. More than 85% of lung

cancers are caused by the inhalation of carcinogenic chemicals, most commonly

cigarette smoke (Schottenfeld, 2000).

Pathophysiology

Lung

cancers arise from a single transformed epithelial cell in the tracheobronchial

airways. A carcinogen (cigarette smoke, radon gas, other occupational and

environmental agents) binds to a cell’s DNA and damages it. This damage results

in cellular changes, ab-normal cell growth, and eventually a malignant cell. As

the dam-aged DNA is passed on to daughter cells, the DNA undergoes further

changes and becomes unstable. With the accumulation of genetic changes, the

pulmonary epithelium undergoes malig-nant transformation from normal epithelium

to eventual inva-sive carcinoma.

Squamous

cell carcinoma is more centrally located and arises more commonly in the

segmental and subsegmental bronchi in response to repetitive carcinogenic

exposures. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent carcinoma of the lung for both

men and women; it presents more peripherally as peripheral masses or nod-ules

and often metastasizes. Large cell carcinoma (also called un-differentiated

carcinoma) is a fast-growing tumor that tends to arise peripherally.

Bronchioalveolar cell cancer arises from the ter-minal bronchus and alveoli and

is usually slower growing as compared to other bronchogenic carcinomas. Lastly,

small cell carcinomas arise primarily as a proximal lesion or lesions but may

arise in any part of the tracheobronchial tree.

Classification and Staging

Non-small

cell carcinoma represents 70% to 75% of tumors; small cell carcinoma represents

15% to 20% of tumors. For non-small cell carcinoma, the cell types include squamous

cell carcinoma (30%), large cell carcinoma (10% to 16%), and adenocarcinoma

(31% to 34%), including bronchioalveolar carcinoma (3% to 4%). Most small cell

carcinomas arise in the major bronchi and spread by infiltration along the

bronchial wall. Small cell cancers account for 20% to 25% of all bronchogenic

cancers (Matthay, Tanoue & Carter, 2000).

In

addition to cell type, lung cancers also are staged. The stage of the tumor

refers to the size of the tumor, its location, whether lymph nodes are involved,

and whether the cancer has spread (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 2002).

Non-small cell lung cancer is staged as I to IV. Stage I is the earliest stage

with the highest cure rates, while stage IV designates metastatic spread.

Small

cell lung cancers are classified as limited or extensive.

Risk Factors

Various

factors have been associated with the development of lung cancer, including

tobacco smoke, second-hand (passive) smoke, environmental and occupational

exposures, gender, ge-netics, and dietary deficits. Other factors that have

been associ-ated with lung cancer include genetic predisposition and other

underlying respiratory diseases, such as COPD and TB.

TOBACCO SMOKE

Tobacco

use is responsible for more than one of every six deaths in the United States

from pulmonary and cardiovascular dis-eases. Smoking is the most important

single preventable cause of death and disease in this country. More than 85% of

lung cancers are attributable to inhalation of carcinogenic chemicals, such as

cigarette smoke (American Cancer Society, 2002). Lung cancer is 10 times more

common in cigarette smokers than non-smokers. Risk is determined by the

pack-year history (number of packs of cigarettes used each day, multiplied by

the number of years smoked), the age of initiation of smoking, the depth of

inhalation, and the tar and nicotine levels in the cigarettes smoked. The

younger a person is when he or she starts smok-ing, the greater the risk of

developing lung cancer. The risk of lung cancer decreases as the duration of

smoking cessation increases.

SECOND-HAND SMOKE

Passive

smoking has been identified as a possible cause of lung cancer in nonsmokers.

In other words, people who are involun-tarily exposed to tobacco smoke in a

closed environment (home, car, building) are at increased risk for developing

lung cancer as compared to unexposed nonsmokers. An average lifetime passive

smoke exposure to a smoking spouse or partner increases a non-smoker’s risk of

lung cancer by about 35% compared to the risk of 100% for a lifetime of active

smoking (Matthay, Tanoue & Carter, 2000).

ENVIRONMENTAL AND OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

Various

carcinogens have been identified in the atmosphere, in-cluding motor vehicle

emissions and pollutants from refineries and manufacturing plants. Evidence

suggests that the incidence of lung cancer is greater in urban areas as a

result of the buildup of pollutants and motor vehicle emissions.

Radon

is a colorless, odorless gas found in soil and rocks. For many years it has

been associated with uranium mines, but it is now known to seep into homes

through ground rock. High levels of radon have been associated with the

development of lung can-cer, especially when combined with cigarette smoking.

Home-owners are advised to have radon levels checked in their houses and to

arrange for special venting if the levels are high.

Chronic

exposure to industrial carcinogens, such as arsenic, asbestos, mustard gas,

chromates, coke oven fumes, nickel, oil, and radiation, has been associated

with the development of lung cancer. Laws have been passed to control exposure

to such ele-ments in the workplace.

GENETICS

Some

familial predisposition to lung cancer seems apparent, be-cause the incidence

of lung cancer in close relatives of patients with lung cancer appears to be

two to three times that of the gen-eral population regardless of smoking

status.

DIETARY FACTORS

Prior

research has demonstrated that smokers who eat a diet low in fruits and

vegetables have an increased risk of developing lung cancer (Bast, Kufe,

Pollock et al., 2000). The actual active agents in a diet rich in fruits and

vegetables have yet to be determined. It has been hypothesized that

carotenoids, particularly carotene or vitamin A, may be important. Several

ongoing trials may help to determine if carotene supplementation has anticancer

proper-ties. Other nutrients, including vitamin E, selenium, vitamin C, fat,

and retinoids, are also being evaluated regarding their pro-tective role

against lung cancer (Bast, Kufe, Pollock et al., 2000).

Clinical Manifestations

Often,

lung cancer develops insidiously and is asymptomatic until late in its course.

The signs and symptoms depend on the location and size of the tumor, the degree

of obstruction, and the existence of metastases to regional or distant sites.

The

most frequent symptom of lung cancer is cough or change in a chronic cough.

People frequently ignore this symptom and attribute it to smoking or a

respiratory infection. The cough starts as a dry, persistent cough, without

sputum production. When obstruction of airways occurs, the cough may become

productive due to infection.

Wheezing

is noted (occurs when a bronchus becomes partially obstructed by the tumor) in

about 20% of patients with lung can-cer. Patients also may report dyspnea. Hemoptysis

or blood-tinged sputum may be expectorated. In some patients, a recurring fever

occurs as an early symptom in response to a persistent in-fection in an area of

pneumonitis distal to the tumor. In fact, can-cer of the lung should be

suspected in people with repeated unresolved upper respiratory tract

infections. Chest or shoulder pain may indicate chest wall or pleural

involvement by a tumor. Pain also is a late manifestation and may be related to

metastasis to the bone.

If

the tumor spreads to adjacent structures and regional lymph nodes, the patient

may present with chest pain and tightness, hoarseness (involving the recurrent

laryngeal nerve), dysphagia, head and neck edema, and symptoms of pleural or

pericardial ef-fusion. The most common sites of metastases are lymph nodes,

bone, brain, contralateral lung, adrenal glands, and liver. Non-specific

symptoms of weakness, anorexia, and weight loss also may be diagnostic.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

If

pulmonary symptoms occur in a heavy smoker, cancer of the lung is suspected. A

chest x-ray is performed to search for pul-monary density, a solitary

peripheral nodule (coin lesion), atelec-tasis, and infection. CT scans of the

chest are used to identify small nodules not visualized on the chest x-ray and

also to exam-ine serially areas of the thoracic cage not clearly visible on the

chest x-ray.

Sputum

cytology is rarely used to make a diagnosis of lung cancer; however, fiberoptic

bronchoscopy is more commonly used and provides a detailed study of the

tracheobronchial tree and allows for brushings, washings, and biopsies of

suspicious areas. For peripheral lesions not amenable to bronchoscopic biopsy,

a transthoracic fine-needle aspiration

may be performed under CT or fluoroscopic guidance to aspirate cells from a

suspi-cious area. In some circumstances, an endoscopy with esophageal

ultrasound (EUS) may be used to obtain a transesophageal biopsy of enlarged

subcarinal lymph nodes that are not easily accessible by other means.

A

variety of scans may be used to assess for metastasis of the cancer. These may

include bone scans, abdominal scans, positron emission tomography (PET) scans,

or liver ultrasound or scans. CT of the brain, magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI), and other neuro-logic diagnostic procedures are used to detect central

nervous sys-tem metastases. Mediastinoscopy or mediastinotomy may be used to

obtain biopsy samples from lymph nodes in the mediastinum.

If

surgery is a potential treatment, the patient is evaluated to determine whether

the tumor is resectable and whether the physiologic impairment resulting from

such surgery can be tol-erated. Pulmonary function tests, arterial blood gas

analysis, ventilation–perfusion scans, and exercise testing may all be used as

part of the preoperative assessment (Knippel, 2001).

Medical Management

The

objective of management is to provide a cure, if possible. Treatment depends on

the cell type, the stage of the disease, and the physiologic status

(particularly cardiac and pulmonary status) of the patient. In general,

treatment may involve surgery, radia-tion therapy, or chemotherapy—or a

combination of these. Newer and more specific therapies to modulate the immune

system (gene therapy, therapy with defined tumor antigens) are under study and

show promise in treating lung cancer.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical

resection is the preferred method of treating patients with localized non-small

cell tumors, no evidence of metastatic spread, and adequate cardiopulmonary

function. If the patient’s cardiovascular status, pulmonary function, and

functional status are satisfactory, surgery is generally well tolerated.

Coronary artery disease, pulmonary insufficiency, and other comorbidities,

how-ever, may contraindicate surgical intervention. The cure rate of surgical

resection depends on the type and stage of the cancer. Surgery is primarily

used for non-small cell carcinomas because small cell cancer of the lung grows

rapidly and metastasizes early and extensively. Unfortunately, in many patients

with broncho-genic cancer, the lesion is inoperable at the time of diagnosis.

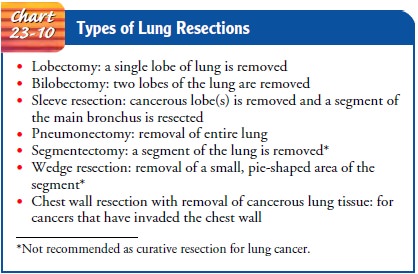

Several

different types of lung resections may be performed (Chart 23-10). The most

common surgical procedure for a small, apparently curable tumor of the lung is

lobectomy (removal of a lobe of the lung). In some cases, an entire lung may be

removed (pneumonectomy).

RADIATION THERAPY

Radiation therapy may cure a small percentage of patients. It is useful in controlling neoplasms that cannot be surgically resected but are responsive to radiation. Radiation also may be used to re-duce the size of a tumor, to make an inoperable tumor operable, or to relieve the pressure of the tumor on vital structures. It can control symptoms of spinal cord metastasis and superior vena caval compression. Also, prophylactic brain irradiation is used in certain patients to treat microscopic metastases to the brain. Ra-diation may help relieve cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and bone and liver pain. Relief of symptoms may last from a few weeks to many months and is important in improving the qual-ity of the remaining period of life.

Radiation

therapy usually is toxic to normal tissue within the radiation field, and this

may lead to complications such as esophagitis, pneumonitis, and radiation lung

fibrosis. These may impair ventilatory and diffusion capacity and significantly

reduce pulmonary reserve. The patient’s nutritional status, psychologi-cal

outlook, fatigue level, and signs of anemia and infection are monitored

throughout the treatment.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy

is used to alter tumor growth patterns, to treat pa-tients with distant

metastases or small cell cancer of the lung, and as an adjunct to surgery or

radiation therapy. Combinations of two or more medications may be more

beneficial than single-dose regimens. A large number of medications are active

against lung cancer. A variety of chemotherapeutic agents are used, including

alkylating agents (ifosfamide), platinum analogues (cisplatin and carboplatin),

taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel), vinca alkaloids (vinblastine and vindesine),

doxorubicin, gemcitabine, vinorel-bine, irinotecan (CPT-11), and etoposide

(VP-16). The choice of agent depends on the growth of the tumor cell and the

specific phase of the cell cycle that the medication affects. Numerous

com-binations of chemotherapy are undergoing investigation to iden-tify the

optimal regimen to treat differing types of lung cancer.

Chemotherapy

may provide relief, especially of pain, but it does not usually cure the

disease, nor does it often prolong life to any great degree. Chemotherapy is

also accompanied by side effects. It is valuable in reducing pressure symptoms

of lung cancer and in treating brain, spinal cord, and pericardial metastasis.

PALLIATIVE THERAPY

Palliative

therapy may include radiation therapy to shrink the tumor to provide pain

relief, a variety of bronchoscopic inter-ventions to open a narrowed bronchus

or airway, and pain man-agement and other comfort measures. Evaluation and referral

for hospice care are important in planning for comfortable and dig-nified

end-of-life care for the patient and family.

Treatment-Related Complications

A

variety of complications may occur as a result of lung cancer treatments.

Radiation therapy may result in diminished cardio-pulmonary function and other

complications, such as pulmonary fibrosis, pericarditis, myelitis, and cor

pulmonale. Chemotherapy, particularly in combination with radiation therapy,

can cause pneumonitis. Pulmonary toxicity is a potential side effect of

chemotherapy. Surgical resection may result in respiratory fail-ure,

particularly when the cardiopulmonary system is compro-mised before surgery.

Surgical complications and prolonged mechanical ventilation are potential

outcomes.

Nursing Management

Nursing

care of the patient with lung cancer is similar to that of other patients with

cancer and addresses the phys-iologic

and psychological needs of the patient. The physiologic problems are primarily

due to the respiratory manifestations of the disease. Nursing care includes

strategies to ensure relief of pain and discomfort and to prevent

complications.

MANAGING SYMPTOMS

The

nurse instructs the patient and family about the potential side effects of the

specific treatment and strategies to manage them. Strategies for managing such

symptoms as dyspnea, fa-tigue, nausea and vomiting, and anorexia will assist

the patient and family to cope with the therapeutic measures.

RELIEVING BREATHING PROBLEMS

Airway

clearance techniques are key to maintaining airway patency through the removal

of excess secretions. This may be accomplished through deep-breathing

exercises, chest physiotherapy, directed cough, suctioning, and in some

instances bronchoscopy. Bron-chodilator medications may be prescribed to

promote bronchial dilation. As the tumor enlarges or spreads, it may compress a

bronchus or involve a large area of lung tissue, resulting in an im-paired

breathing pattern and poor gas exchange. At some stage of the disease,

supplemental oxygen will probably be necessary.

Nursing

measures focus on decreasing dyspnea by encourag-ing the patient to assume

positions that promote lung expansion, breathing exercises for lung expansion

and relaxation, and edu-cating the patient on energy conservation and airway

clearance techniques (Connolly & O’Neill, 1999). Many of the techniques

used in pulmonary rehabilitation can be applied to the lung can-cer patient.

Depending on the severity of disease and the patient’s wishes, a referral to a

pulmonary rehabilitation program may be helpful in managing respiratory

symptoms.

REDUCING FATIGUE

Fatigue

is a devastating symptom that affects quality of life in the cancer patient. It

is commonly experienced by the lung cancer pa-tient and may be related to the

disease itself, the cancer treatment and complications (eg, anemia), sleep

disturbances, pain and dis-comfort, hypoxemia, poor nutrition, or the

psychological ramifi-cations of the disease (eg, anxiety, depression). The

nurse is pivotal in thoroughly assessing the patient’s level of fatigue,

identifying potentially treatable causes, and validating with the patient that

fatigue is indeed an important symptom. Educating the patient in energy

conservation techniques or referring the patient to a physical therapy, occupational

therapy, or pulmonary rehabilita-tion program may be helpful. In addition,

guided exercise has been recently identified as a potential intervention for

treating fatigue in cancer patients. This is an important area for research

because few studies have been conducted, and only in select pop-ulations of

cancer patients.

PROVIDING PSYCHOLOGICAL SUPPORT

Another

important part of the nursing care of the patient with lung cancer is

psychological support and identification of poten-tial resources for the

patient and family. Often, the nurse must help the patient and family deal with

the poor prognosis and rel-atively rapid progression of this disease. The nurse

must help the patient and family with informed decision making regarding the

possible treatment options, methods to maintain the patient’s quality of life

during the course of this disease, and end-of-life treatment options.

Related Topics