Chapter: Biochemistry: Nucleic Acids: How Structure Conveys Information

The Human Genome Project: Treasure or PandoraŌĆÖs Box?

The Human Genome Project:

Treasure or PandoraŌĆÖs Box?

The

Human Genome Project (HGP) was a massive attempt to sequence the entire human

genome, some 3.3 billion base pairs spread over 23 pairs of chromosomes. This

project, started formally in 1990, is a worldwide effort driven forward by two

groups. One is a private company called Celera Genomics, and its preliminary

results were published in Science in

February 2001. The other is a publicly funded group of researchers called the

International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Their preliminary results

were published in Nature in February

2001. Researchers were surprised to find only about 30,000 genes in the human

genome. This figure has since dwindled to 25,000. This is similar to many other

eukaryotes, including some as simple as the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans.

What

does one do with the information? From this informa-tion, we will eventually be

able to identify all human genes and to determine which sets of genes are

likely to be involved in all human genetic traits, including diseases that have

a genetic basis. There is an elaborate interplay of genes, so it may never be

possible to say that a defect in a given gene will ensure that the individual

will develop a particular disease. Nevertheless, some forms of genetic

screening will certainly become a routine part of medical testing in the

future. It would be beneficial, for example, if someone more susceptible to

heart disease than the average person were to have this information at an early

age. This person could then decide on some minor adjustments in lifestyle and

diet that might make heart disease much less likely to develop.

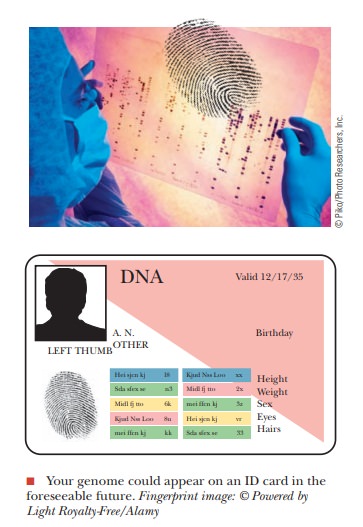

Many

people are concerned that the availability of genetic information could lead to

genetic discrimination. For that rea-son, HGP is a rare example of scientific

project in which definite percentages of financial support and research effort

have been devoted to the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of the

research. The question is often posed in this form: Who has a right to know

your genetic information? You? Your doctor? Your potential spouse or employer?

An insurance company? These questions are not trivial, but they have not yet

been answered definitively. The 1997 movie Gattaca

depicted a society in which oneŌĆÖs social and economic classes are established

at birth based on oneŌĆÖs genome. Many citizens have expressed concern that

genetic screening would lead to a new type of prejudice and big-otry aimed

against ŌĆ£genetically challengedŌĆØ people. Many people have suggested that there

is no point in screening for potentially disastrous genes if there is no

meaningful therapy for the dis-ease they may ŌĆ£cause.ŌĆØ However, couples often

want to know in advance if they are likely to pass on a potentially lethal

disease to their children.

Two specific examples are

pertinent here:

There is no advantage in

testing for the breast-cancer gene if a woman is not in a family at high risk for the disease. The presence of a

ŌĆ£normalŌĆØ gene in such a low-risk individual tells nothing about whether a

mutation might occur in the future. The risk of breast cancer is not changed if

a low-risk person has the normal gene, so mammograms and monthly

self-examination are in order.

The

presence of a gene has not always predicted the develop-ment of the disease.

Some individuals who have been shown to be carriers of the gene for

HuntingtonŌĆÖs disease have lived to old age without developing the disease. Some

males who are functionally sterile have been found to have cystic fibro-sis,

which carries a side effect of sterility due to the improper chloride-channel

function that is a feature of that disease. They learn this when they go to a

clinic to assess the nature of their fertility problem, even though they may

never have shown true symptoms of the disease as a child, other than perhaps a

high occurrence of respiratory ailments.

Another major area for concern about the HGP is the possibil-ity of gene therapy, which many people fear is akin to ŌĆ£playing God.ŌĆØ Some people envision an era of so-called designer babies, with attempts made to create the ŌĆ£perfectŌĆØ human. A more mod-erate view has been that gene therapy may be useful in correcting diseases that impair life or are lethal. Tests with human subjects are already underway for cystic fibrosis, the ŌĆ£bubble boyŌĆØ type of immune deficiency, and some other diseases. Current guidelines in the United States allow for gene therapy of somatic cells, but they do not allow for genetic modifications that would be passed on to the next generation.

Related Topics