Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Dysfunction

The Epilepsies

THE EPILEPSIES

Epilepsy

is a group of syndromes

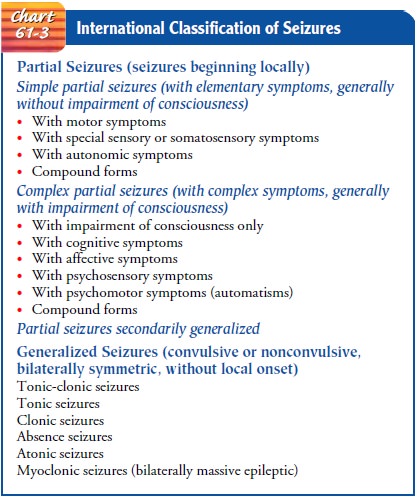

characterized by recurringseizures. Epileptic syndromes are classified by

specific patterns of clinical features, including age of onset, family history,

and seizure type (Schachter, 2001). Types of epilepsies are differentiated by

how the seizure activity manifests (see Chart 61-3), the most common syndromes

being those with generalized seizures and those with partial-onset seizures.

Epilepsy can be primary (idio-pathic) or secondary, when the cause is known and

the epilepsy is a symptom of another underlying condition such as a brain tumor

(Schachter, 2001).

An estimated 2 to 4 million people in the United States have epilepsy (1 in 100 adults is affected), and onset occurs before the age of 20 years in greater than 75% of patients (Schacter, 2001). The improved treatment of cerebrovascular disorders, head in-juries, brain tumors, meningitis, and encephalitis has increased the number of patients at risk for seizures following recovery from these conditions (Berges et al., 2000). Also, advances in EEG have aided in the diagnosis of epilepsy. The general public has been educated about epilepsy, which has reduced the stigma as-sociated with it; as a result, more people are willing to acknowl-edge the diagnosis.

Although there is evidence that susceptibility to

some types of epilepsy may be inherited, the cause of seizures in many people

is unknown. Epilepsy can follow birth trauma, asphyxia neonatorum, head

injuries, some infectious diseases (bacterial, viral, parasitic), toxicity

(carbon monoxide and lead poisoning), circu-latory problems, fever, metabolic

and nutritional disorders, and drug or alcohol intoxication (Schachter, 2001).

It is also associ-ated with brain tumors, abscesses, and congenital

malformations. In most cases of epilepsy, the cause is unknown (idiopathic).

Pathophysiology

Messages

from the body are carried by the neurons (nerve cells) of the brain by means of

discharges of electrochemical energy that sweep along them. These impulses

occur in bursts whenever a nerve cell has a task to perform. Sometimes, these

cells or groups of cells continue firing after a task is finished. During the

period of unwanted discharges, parts of the body controlled by the er-rant

cells may perform erratically. Resultant dysfunction ranges from mild to

incapacitating and often causes unconsciousness (Greenberg, 2001; Hickey,

2003). When these uncontrolled, ab-normal discharges occur repeatedly, a person

is said to have an epileptic syndrome (Schachter, 2001).

Epilepsy

is not associated with intellectual level. People with epilepsy without other

brain or nervous system disabilities fall within the same intelligence ranges

as the overall population. Epilepsy is not synonymous with mental retardation

or illness. Many who are developmentally disabled because of serious

neu-rologic damage, however, have epilepsy as well.

Clinical Manifestations

Depending on the location of the discharging

neurons, seizures may range from a simple staring episode to prolonged

convulsive movements with loss of consciousness. Seizures have been classi-fied

according to the area of the brain involved and have been identified as

partial, generalized, and unclassified (Greenberg, 2001; Hickey, 2003). Partial

seizures are focal in origin and af-fect only part of the brain. Generalized

seizures are nonspecific in origin and affect the entire brain simultaneously.

Unclassified seizures are so termed because of incomplete data.

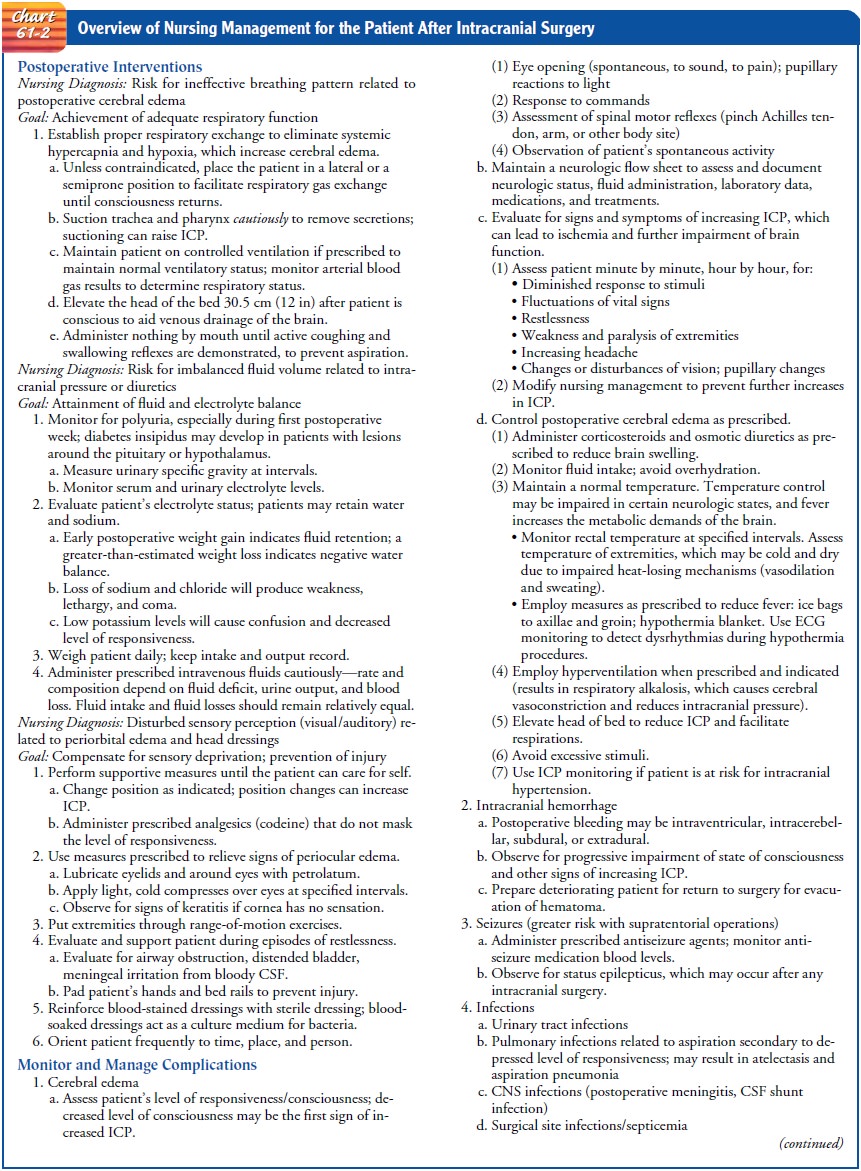

The

initial pattern of the seizures indicates the region of the brain in which the

seizure originates (see Chart 61-2). In simple partial seizures, only a finger

or hand may shake, or the mouth may jerk uncontrollably. The person may talk

unintelligibly, may be dizzy, and may experience unusual or unpleasant sights,

sounds, odors, or tastes, but without loss of consciousness (Greenberg, 2001;

Hickey, 2003).

In

complex partial seizures, the person either remains mo-tionless or moves automatically

but inappropriately for time and place, or may experience excessive emotions of

fear, anger, ela-tion, or irritability. Whatever the manifestations, the person

does not remember the episode when it is over.

Generalized

seizures, previously referred to as grand mal seizures, involve both

hemispheres of the brain, causing both sides of the body to react (Greenberg,

2001; Hickey, 2003). There may be intense rigidity of the entire body followed

by alternating muscle relaxation and contraction (generalized tonic–clonic

contrac-tion). The simultaneous contractions of the diaphragm and chest muscles

may produce a characteristic epileptic cry. The tongue is often chewed, and the

patient is incontinent of urine and stool. After 1 or 2 minutes, the convulsive

movements begin to subside; the patient relaxes and lies in deep coma,

breathing noisily. The respirations at this point are chiefly abdominal. In the

postictal state (after the seizure), the patient is often confused and hard to

arouse and may sleep for hours. Many patients complain of headache, sore

muscles, fatigue, and depression (Buelow, 2001).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

diagnostic assessment is aimed at determining the type of seizures, their

frequency and severity, and the factors that pre-cipitate them (Schachter,

2001). A developmental history istaken, including events of pregnancy and

childbirth, to seek evi-dence of preexisting injury. The patient is also

questioned about illnesses or head injuries that may have affected the brain. In

ad-dition to physical and neurologic evaluations, diagnostic exami-nations

include biochemical, hematologic, and serologic studies. MRI is used to detect

lesions in the brain, focal abnormalities, cerebrovascular abnormalities, and

cerebral degenerative changes (Schachter, 2001).

The electroencephalogram (EEG) furnishes diagnostic

evi-dence in a substantial proportion of patients with epilepsy and aids in

classifying the type of seizure (Schachter, 2001). Abnor-malities in the EEG

usually continue between seizures or, if not apparent, may be elicited by

hyperventilation or during sleep. Microelectrodes can be inserted deep in the

brain to probe the action of single brain cells. Some people with seizures have

nor-mal EEGs, whereas others who have never had seizures have ab-normal EEGs.

Telemetry and computerized equipment are used to monitor electrical brain

activity while patients pursue their normal activities and to store the

readings on computer tapes for analysis. Video recording of seizures taken simultaneously

with EEG telemetry is useful in determining the type of seizure as well as its

duration and magnitude. This type of intensive monitoring is changing the

treatment of severe epilepsy.

Single

photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is an additional tool sometimes

used in the diagnostic workup. It is useful for identifying the epileptogenic

zone so that the area in the brain giving rise to seizures can be removed

surgically (Huntington, 1999).

Women With Epilepsy

More

than 1 million American women have epilepsy, and they face particular needs

associated with the syndrome (Schachter, Krishnamurthy & Cantrell, 2000).

Women with epilepsy often note an increase in seizure frequency during menses;

this has been linked to the increase in sex hormones that alter the

excitability of neurons in the cerebral cortex. Women of childbearing age

re-quire special care and guidance before, during, and after preg-nancy. Many

women note a change in the pattern of seizure activity during pregnancy. Fetal

malformation has been linked to the use of multiple antiseizure medications

(Karch, 2002). The effectiveness of contraceptives is decreased by antiseizure

med-ications. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to discuss family

planning with their primary health care provider and to obtain preconception

counseling if they are considering child-bearing (Liporace, 1997).

Because

of bone loss associated with the long-term use of anti-seizure medications,

patients receiving antiseizure agents should be assessed for low bone mass and

osteoporosis. They should be instructed about other strategies to reduce their

risks for osteoporosis.

Gerontologic Considerations

Elderly people have a high incidence of new-onset

epilepsy (Schachter, 2001). Increased incidence is associated with stroke, head

injury, dementia, infection, alcoholism, and aging. Treat-ment depends on the

underlying cause. Because many elderly people have chronic health problems,

they may be taking other medications that can interact with medications

prescribed for seizure control. In addition, the absorption, distribution,

metab-olism, and excretion of medications are altered in the elderly as a

result of age-related changes in renal and liver function. Therefore, the

elderly must be monitored closely for adverse and toxic effects of antiseizure

medications and for osteoporosis. The cost of antiseizure medications can lead

to poor adherence to the pre-scribed regimen in elderly patients on fixed

incomes.

Prevention

Society-wide efforts are the key to the prevention

of epilepsy. The risk for congenital fetal anomaly is two to three times higher

in mothers with epilepsy. The effects of maternal seizures, antiseizure

medications, and genetic predisposition are all mechanisms that contribute to

possible malformation. Because the unborn infants of mothers who take certain

antiseizure medications for epilepsy are at risk, these women need careful

monitoring, including blood studies to detect the level of antiseizure

medications taken through-out pregnancy (Karch, 2002). High-risk mothers

(teenagers, women with histories of difficult deliveries, drug use, patients

with diabetes or hypertension) should be identified and moni-tored closely

during pregnancy because damage to the fetus during pregnancy and delivery may

increase the risk for epilepsy. All of these issues need further study

(Schachter, Krishnamurthy & Cantrell, 2000).

Head

injury is one of the main causes of epilepsy that can be prevented.

Medical Management

The

management of epilepsy is individualized to meet the needs of each patient and

not just to manage and prevent seizures. Man-agement differs from patient to

patient because some forms of epilepsy arise from brain damage and others are

due to altered brain chemistry.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Many

medications are available to control seizures, although the mechanisms of their

actions are still unknown (Karch, 2002). The objective is to achieve seizure

control with minimal side effects. Medication therapy controls rather than

cures seizures. Medications are selected on the basis of the type of seizure

being treated and the effectiveness and safety of the medications (Shafer,

1999a, 1999b; Winkelman, 1999). If properly prescribed and taken, medications

control seizures in 50% to 60% of patients with recurring seizures and provide

partial control in another 15% to 35%. The condition is not improved by any

available medication in 20% and 35% of patients with generalized and partial

epilepsy, respectively (Devinsky, 1999).

Treatment is usually started with a single medication.

The starting dose and the rate at which the dosage is increased depend on the

occurrence of side effects. The medication levels in the blood are monitored

because the rate of drug absorption varies among patients. Changing to another

medication may be neces-sary if seizure control is not achieved or if toxicity

makes it impossible to increase the dosage. The medication may need to be

adjusted because of concurrent illness, weight changes, or in-creases in

stress. Sudden withdrawal of these medications can cause seizures to occur with

greater frequency or can precipitate the development of status epilepticus

(Greenberg, 2001).

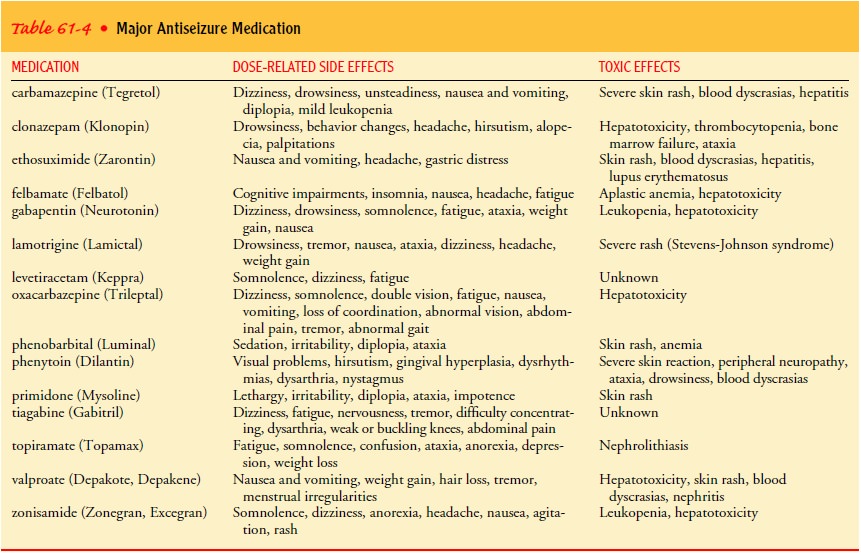

Side effects of antiseizure agents may be divided

into three groups: (1) idiosyncratic or allergic disorders, which present

pri-marily as skin reactions; (2) acute toxicity, which may occur whenthe

medication is initially prescribed; or (3) chronic toxicity, which occurs late

in the course of therapy.

The manifestations of drug toxicity are variable,

and any organ system may be involved. Gingival hyperplasia (swollen and tender

gums) can be associated with long-term use of phenyt-oin (Dilantin), for

example (Karch, 2002). Periodic physical and dental examinations and laboratory

tests are performed for pa-tients receiving medications known to have

hematopoietic, gen-itourinary, or hepatic effects. Table 61-4 lists the

medications in current use.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is indicated for patients whose epilepsy

results from in-tracranial tumors, abscess, cysts, or vascular anomalies. Some

pa-tients have intractable seizure disorders that do not respond to medication.

There may be a focal atrophic process secondary to trauma, inflammation,

stroke, or anoxia. If the seizures originate in a reasonably well-circumscribed

area of the brain that can be excised without producing significant neurologic

deficits, the re-moval of the area generating the seizures may produce

long-term control and improvement (Wiebe, Blume, Girvin et al., 2001).

This type of neurosurgery has been aided by several

advances, including microsurgical techniques, depth EEGs, improved

illu-mination and hemostasis, and the introduction of neurolept-analgesic

agents (droperidol and fentanyl). These techniques, combined with use of local

anesthetic agents, enable the neuro-surgeon to perform surgery on an alert and

cooperative patient. Using special testing devices, electrocortical mapping,

and the pa-tient’s response to stimulation, the boundaries of the

epilepto-genic focus are determined (Huntington, 1999). Any abnormal

epileptogenic focus (ie, abnormal area of the brain) is then re-moved (Wiebe et

al., 2001).

As an adjunct to medication and surgery in

adolescents and adults with partial seizures, a generator may be implanted

under the clavicle. The device is connected to the vagus nerve in the cervical

area, where it delivers electrical signals to the brain to control and reduce

seizure activity (Kennedy & Schallert, 2001). An external programming

system is used by the physician to change stimulator settings. Patients can

turn the stimulator on and off with a magnet.

Related Topics