Intellectual Awakening and Socio-Political Changes | History - Rise of Kingdoms | 9th Social Science : History : Intellectual Awakening and Socio-Political Changes

Chapter: 9th Social Science : History : Intellectual Awakening and Socio-Political Changes

Rise of Kingdoms

Rise of Kingdoms

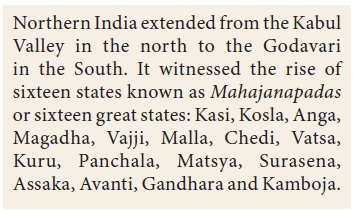

The 6th century BCE witnessed the establishment of

kingdoms, oligarchies and chiefdoms as well as the emergence of towns. From the

largest of the chiefdoms emerged kingdoms. Many tribes of Rig Vedic period such

as Bharatas, Pasus, Tritsus and Turvasas passed into oblivion and new tribes

such as the Kurus and Panchalas rose into prominence. Sixteen mahajanapadas are listed in the Buddhist texts. Linguistic and cultural

commonality prevailed in the janapadas,

whereas in the mahajanapadas,

different social and cultural groups

lived. With the emergence of kingdoms, the struggle for supremacy among

different states occurred frequently. Sacrifices such as Rajasuya and Asvamedha

were performed to signify the imperial sway of monarchs over their rivals. The

Rig Vedic title of ‘Rajan’ was replaced by impressive titles such as Samrat,

Ekrat, Virat or Bhoja.

Growth of Royal Power

The king enjoyed absolute power. The sabha of the Rig Vedic period ceased to exist. The king sought the aid and

support of the samiti on matters like

war, peace and fiscal policies. However, in spite of the existence of the

assemblies, the power of the king kept increasing. The Satapatha Brahmana describes

the king as infallible and immune

from all punishments. The growth of royal power was reflected in the enlarged

administrative structure. The king was now assisted by a group of officers such

as Bhugadugha (collector of taxes), Suta (charioteer), the Aksharapa (superintendent of gambling), Kshattri (chamberlin), Gorikartana (king’s companion in the

chase), Palogola (courtier), Takshan (carpenter) and Rathakara (chariotmaker). In addition,

there were the ecclesiastical and military officials like the Purohita (chaplain), the Senani (army general) and the Gramani (leader of the village).In the

later Vedic period, Gramani, who acted both a civil and military officer, was

the link through which the royal authority was enforced in the village. The

king administered justice and occasionally delegated his judicial power to Adhyakshas (royal officials). In the

villages, Gramyavadin (village judge)

and Sabha (court) decided the cases.

Punishments for crimes were severe.

The Rise of Magadha Kingdom

The polity followed in kingdoms was different from

that of gana-sanghas. Kingdoms operated with a centralised government.

Political power was concentrated in the ruling family, which had become a

dynasty, with succession becoming hereditary. There were advisory bodies such

as parishad (ministers) and sabha (advisory council). The sabha collected the revenue and

remitted it to the treasury in the capital of the kingdom, from where it was

redistributed for the public expenses, such as maintenance of army and salaries

to state officials.

Of the kingdoms mentioned in the literature of the

period, Kashi, Kosala and Magadha are considered to be powerful. The only

republic that rivalled these kingdoms was the Vrijjis, whose capital was

Vaisali. In the struggle for control for the Gangetic Plain, which had

strategic and economic advantages, the Magadha kingdom emerged victorious.

Bimbisara was the first important king of Magadha. Through matrimonial

alliances with the high-status Lichchavi clan of Vaishali and the ruling family

in Kosala, Bimbisara went on to conquer Anga (in West Bengal now), thereby

gaining access to the Ganges delta.

Bimbisara succeeded in establishing a comprehensive structure of administration. Village was the basic unit of his administrative system. Apart from villages (gramas), there were fields and pastures as well as wasteland and the forests (aranya, khetra and vana). Each village was brought under a gramani (headman), who was responsible for collecting taxes and remitting them to the state treasury. Officers appointed to measure the land under cultivation and assess the value of crop were to assist the gramani in his task. Land tax (bali) was the main source of revenue to the kingdom and the share of the produce (bhaga) was determined proportionate to the extent of land cultivated. The term shadbhagin – one who is entitled to a share of one-sixth –referred to the king. Thus, a peasant economy came into being at Magadha.

Ajatashatru, the son of Bimbisara, is said to have

murdered his father and ascended the throne in 493 BCE. He continued his

father’s policy of expansion through military conquests. The capital city of

Magadha was Rajagriha, which was surrounded by five hills, providing protection

to the kingdom from external threats. Ajatashatru strengthened the Rajagriha

fort and also built another fort at Pataligrama on the Ganges. It served as the

exchange centre for the local produce and later became the Mauryan capital of

Pataliputra. Ajastashatru died in 461 BCE and he was succeeded by five kings.

All of them followed the example of Ajatashatru by ascending the throne by

killing their parent. Fed up with such recurring instances, people of Magadha

appointed the last ruler’s viceroy Shishunaga as the king. After ruling nearly

for half a century, the Shishunaga dynasty lost the kingdom to Mahapadma Nanda

who founded the Nanda dynasty. The Nandas were the first of non-kshatriya

dynasties to rule in northern India.

Nandas extended the Magadhan Empire still further.

Nandas gave importance to irrigation, with the canals they built touching even

the Kalinga (Odisha) kingdom. During their period, officials were regularly

appointed to collect the taxes which became a part of the administrative

system. Nandas’ attempt to build an imperial structure was cut short by

Chandragupta Maurya who founded the Mauryan kingdom in 321 BCE.

Related Topics